Bibliography of Quoted Sources

W. Alister Williams, Against the Odds; The Life of Group Captain Lionel Rees VC, (Wrexham: Bridge Books, 1989)

H. H. Balfour, An Airman Marches, (London: Hutchinson & Co, 1933)

M. Baring, Flying Corps Headquarters, (Edinburgh & London: William Blackwood & Sons, 1968)

A. Bott, Cavalry of the Clouds, (New York: Doubleday Page & Company, 1918)

A. Boyle, Trenchard , (London: Collins, 1962)

W. A. Briscoe & H Russell Stannard, Captain Ball, VC, (London: Herbert Jenkins Ltd, 1918)

W. Churchill, World Crisis , 1911-1918 (London: Odhams Press, 1938)

C. Cole RFC Communiques, 1915-1916 , (London: Kimber, 1969)

C. H. Cooke, Historical Records of the 19th (Service) Battalion Northumberland Fusiliers,

(Newcastle upon Tyne: Chamber of Commerce, 1920)

A. J. Evans, The Escaping Club, (London: John Lane The Bodley Head Ltd, 1921)

Extracts from German Documents and Correspondence, (SS 473)

Extracts No 2 from German Documents and Correspondence, (SS 515)

Final Report of the Committee on the Administration and Command of the Royal Flying

Corps, (London: HMSO, 1916)

H. Gough, The Fifth Army, (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1931)

B. G. Gray & the DH2 Research Group, The Anatomy of an Aeroplane: The de Havilland DH2

Pusher Scout, (Cross & Cockade)

H. E. Hartney, Wings over France, (Folkestone: Bailey Brothers, 1974)

W. F. J. Harvey, Pi in the Sky: A history of No. 22 Squadron, Royal Flying Corps and RAF in

the War of 1914-1918, (1969)

T. Hawker, Hawker VC, (London: Mitre Press, 1965)

General Staff Intelligence I Corps, Notes on the Interpretation of Aeroplane Photographs,

12/1916

L. F. Hutcheon, War Flying , (London: John Murray, 1917)

F. Immelmann, Max Immelmann: Eagle of Lille , (London: John Hamilton, ca 1930)

H. A. Jones, Official History of the War: The War in the Air, Being the Story of the part

played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1922-1937)

Interim Report of the Committee on the Administration and Command of the Royal Flying

Corps, (London: HMSO, 1916)

R. H. Kiernan, Captain Albert Ball, (London: Aviation Book Club, 1939)

G. Lewis, Wings Over the Somme, (Wrexham: Bridge Books, 1994)

E. Ludendorf, My War Memories, 1914-1918, (London: Hutchinson)

J. T. B. McCudden, Five Years in the Royal Flying Corps, (London: Aeroplane & General, 1918)

R. R. Money, Flying and Soldiering, (London: Ivor Nicholson & Watson Limited, 1936)

M. von Richthofen, The Red Airfighter , (London: Greenhill Books, 1990)

M. von Richthofen, The Red Baron: Translated by Peter Kilduff, (Folkestone: Bailey Brothers

& Swinfen Ltd, 1974)

M. von Richthofen, The Red Baron, (Folkestone: Bailey Brothers & Swinfen Ltd, 1974)

H. Schroder, An Airman Remembers, (London: John Hamilton, ca 1939)

A. J. L. Scott, Sixty Squadron, RAF: A History of the Squadron, 1916-1919, (London: Greenhill Books, 1990)

C. R. Tidswell, Letters from Cecil Robert Tidswell, (Privately published)

Various, Naval Eight: A history of No. 8 Squadron, RNAS, (London: The Signal Press, 1931)

J. Werner, Knight of Germany: Oswald Boelcke German Ace, (London: John Hamilton Ltd, 1933)

S. F. Wise, Canadian Airmen and the First World War: The Official History of the Royal Canadian Air Force Volume I , (Toronto, University of Toronto Press)

Chapter One

In the Beginning...

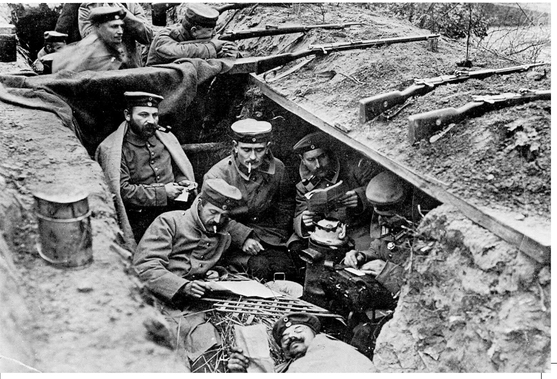

In the beginning there was the ground war. The entrenched armies faced each other across No Mans Land all along the Western Front; an inviolable line that marked the end of the brief period of open warfare in 1914. As the armies crashed into each other the soldiers scratched themselves impromptu cover when it seemed certain death to stay above ground. They sought sanctuary from the streams of machine gun bullets and crashing detonations of artillery shells that typified modern warfare. Gradually these tentative scrapings were deepened and extended until an unbroken front was created from which they could pour fire into any attack made upon them. So the line froze into immobility. Gradually a second or third line was dug and the whole system interconnected with communication trenches that allowed the troops to come into the line without ever raising their heads above the trench parapets. At first both sides were relatively confident that these trenches were temporary resting places, while they girded their metaphorical loins for the next great attack that would surely rupture the enemys line, allowing a resumption of old style open warfare, culminating in an enjoyably satisfying advance to victory in Berlin or Paris depending on perspective. However, for all their initial optimism, it was an intractable problem that faced the generals in 1915 and their pre-war experience was to prove of little or no value.

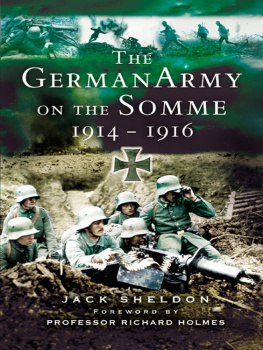

German troops relaxing in a shallow trench.

There was another new factor. Though before the war the military value of the aeroplane had been clearly recognized, the first powered flight by the Wright brothers had only taken place eleven years earlier in 1903. Aircraft were developing rapidly, but their limitations in 1914 were considerable. Speeds were dangerously low and the margin between safe flying and stalling speed was often extremely narrow. Although some aircraft had flown at over 100mph the bulk of aircraft flew at between 60 and 80mph. Methods of controlling movement in the air were not fully understood and consequently aerial manoeuvres were often carried out on the basis of guesswork; simply repeating actions that had not actually resulted in disaster last time they were tried. The science of aeronautics was literally in its infancy. Underpowered as they were, the amount of weight that each aircraft could lift was severely limited and this hindered any attempt to develop any real military strike role by deploying bombs or machine guns. The immediate practical military interest in the aircraft centred on the obvious possibilities of aerial reconnaissance. Aircraft offered the embattled general the opportunity for observers to rise above the confusion of battle and gain access to the minutiae of his opponents dispositions and movements. Reams of vital intelligence could be harvested at the risk of just a few daring aviators flying deep into enemy territory, rather than the much more limited results offered by the conventional reconnaissance in force by cavalry. Although the Great Powers invested to some degree in aircraft before the war, rigid airships were seen by many as a far more promising method of pursuing aerial warfare. Not only did airships have a far greater range of operations, but they could also lift significant bomb loads, with which to hopefully destroy their enemies when they found them.

By 1912 the military was showing a keen interest in aviation; here British Army Aeroplane model No.1, designed by Samuel Cody, is being wheeled out for a test flight. The classic aircraft shape had yet to emerge.

The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) had gone to war under the command of Sir David Henderson with just four squadrons, that in all totalled some 63 serviceable aircraft. The primitive state of aircraft technology can be judged by the fact that it was still considered a remarkable feat that they had managed to cross the English Channel under their own power. After all, the first successful cross-Channel flight by the redoubtable Louis Blriot had only been completed five years previously. Once there, the RFC soon proved its value by helping to expose the workings of the German Schlieffen plan to the initially sceptical British Commander in Chief Sir John French. It was their reconnaissance reports that provided a basis for the Allied reorganization and counter-attack at the Battle of the Marne.