An officer of the Royal Engineers stands on the ruins of in La Boisselle Church, July 1916.

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Richard van Emden 2016

ISBN: 978 1 47385 521 2

PDF ISBN: 978 1 47385 524 3

EPUB ISBN: 978 1 47385 522 9

PRC ISBN: 978 1 47385 523 6

The right of Richard van Emden to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in Ehrhardt by

Mac Style Ltd, Bridlington, East Yorkshire

Printed and bound in China by Imago

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, and Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

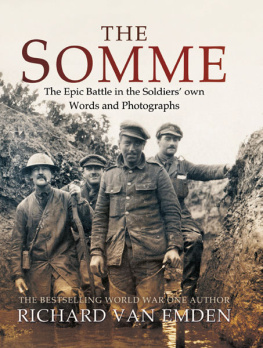

Title Page: Captain Ormonde Whiteman looks through a periscope. He was killed in November, 1917.

To the memory of Sapper Norman Ralph Skelton, 18981988 103915, Wireless Section, Royal Engineers

and

Alicia Wilson, aged 104, daughter of Captain Hugh Russell Wilson, C Coy, 1/5th Durham Light Infantry, killed in action 11 September 1916, buried Bcourt Cemetery, Somme

My dear George and Alicia

Thank you both so very much for sending me such nice photographs, you are kind and you do look well and pretty. I am having such a nice birthday. I got up at 6 oclock and went for a ride on a mule, or as we call them, a Moke. It is half a horse and half a donkey and is called Billy. I am going to a party tonight and hope to enjoy myself. There are lots of guns round about us and they do make a row, Im sure they would wake you up if you had them going off near you in the night. Daisy is quite well but she will gallop so and it makes her far too hot. I hope you enjoy Harrogate. Mind, be kind to Granny and Grandpa and be good children.

Your affectionate

Daddy

[Captain Hugh Wilson, written on his 38th birthday, 2nd August 1916]

Officers and men of the 8th East Lancashire Regiment in the waterlogged trenches near Foncquevillers, winter 1915.

CONTENTS

Horses belonging to the 1/6th Seaforth Highlanders are taken through a village on the Somme, summer 1915.

Introduction

There was no mistaking the importance of this enormous struggle [on the Somme], for the roads were almost jammed with night traffic for many miles, and vast stores of shells lay in the fields. Burdened ration-carts rumbled by. Guns each drawn by a team of straining horses, thundered on. Officers in flowing rain-cloaks and mounted orderlies clattered along the stony sidewalks. Infantrymen, grey with mud, tramped with pick and spade. Cyclist orderlies threaded a perilous way, like Cockney youths rushing evening papers through the streets.

Sergeant William Andrews, 4/5th The Black Watch

I dealism perished on the Somme, according to the historian A.J.P. Taylor. The enthusiastic volunteers were enthusiastic no longer. They had lost faith in their cause, in their leaders, in everything except loyalty to their fighting comrades. The war ceased to have a purpose. It went on for its own sake, as a contest of endurance.

In recent years, the views of A.J.P. Taylor have fallen victim to a new and vigorous revisionism, and his sentiments, honed in the 1960s, now seem too crude and subject to the prevailing attitudes of the time: that the war was a hopeless slaughter prosecuted by British generals who were in the main rotten and out of their depth. Most historians would now question whether indeed the war had ceased to have a purpose in soldiers eyes, or whether these young men had really lost faith in their leaders and the cause. But in one way his sentiments still strike the right note: the Somme changed the mindset of those who fought. This battle brought home to the men and senior officers too the blunt understanding that to beat Germany would require an attritional campaign over an extended period, and at terrible cost to all sides. Germany had to be beaten on the Western Front: expensive sideshows, such as the campaign on the Gallipoli peninsula, had proved that there was no cheap and easy alternative. In that sense, the fighting did continue as a contest of endurance while enthusiasm was replaced by a stubborn and resigned determination to win. Before the Somme, there was still public optimism that the war could be won with one great masterstroke, men borne to victory on a tide of enthusiasm rather than professionalism, and so, in that narrowly defined sense, idealism did perish on the Somme.

This is not an exhaustive study of the campaign, analyzing the progress of the battle wood by wood, valley by valley, trench by trench. I, for one, find this history wearying, not because the witnesses are not remarkable diarists or correspondents, but because it is possible to suffer a readers form of battlefield fatigue, battered by descriptions of brutality and increasingly impervious to the human cost. The losses of the first day of the Somme, 20,000 killed and 40,000 wounded, are, in theory, staggering but they are the most commonly used statistic of the Great War and have now lost almost all their power to shock, leave alone visualize. This book is not then a blow-by-blow account of the fighting but rather a detailed impression of what it was like to serve on the Somme.

Next page