The undying spirit of comradeship.

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright holders of material reproduced in this book, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers would be glad to hear from them. For legal purposes the constitute an extension of the copyright page

To find out more about our authors and their books please visit www.bloomsbury.com where you will find extracts, author interviews and details of forthcoming events, and to be the first to hear about latest releases and special offers, sign up for our newsletters here

The 2nd Dragoon Guards (Queen's Bays) in Ploegsteert Wood.

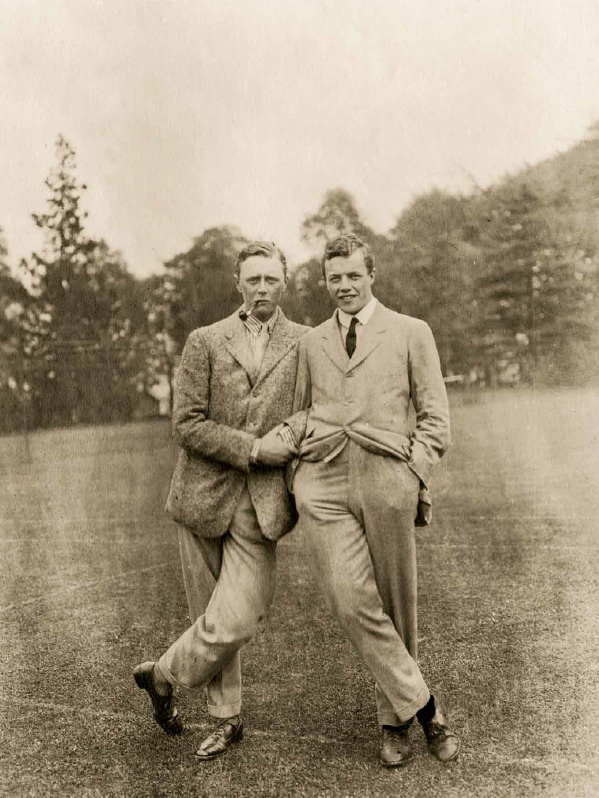

Britains brightest and best: Maurice Browne (left), Coldstream Guards, killed September 1915, and Richard Stokes, MC and Bar, Royal Field Artillery, Captain of Downside School, later Labour Party MP and Lord Privy Seal. Nephew of Sir Wilfred Stokes, the inventor of the Stokes mortar

Introduction

Most of the time the infantry soldier is a navvy with the chance of being killed. During his four or six days in the trenches, he may have many things to complain about, but being idle is not one of them.

An anonymous Scotsman, 1915

The Great War is so much more than the sum of its military engagements: it is an endlessly gripping story of another world that kept a generation of young men and women in its thrall for more than four long years. Perhaps too often the story has been told through its campaigns and battles from August 1914 until the Armistice in November 1918. In contrast, this book creates a new, more immediate and personal narrative of the war, focusing on the individual soldiers physical, mental and emotional experience.

Tommys War is the culmination of more than twenty-five years research into the lives of our soldiers who served a hundred years ago on the Western Front, and it draws exclusively on the soldiers experience in their own words and images, written and taken at the time.

Letters and diaries have an immediacy, a sense of personal urgency, about them, especially when they are scribbled down during or directly after the incident being described. I write this [letter] by the light of a candle stuck at the bottom of an empty tumbler, wrote Lieutenant Eliot Crawshay-Williams, 110th Battery, Royal Field Artillery, as he sailed to France in June 1915. The electric light of the troopship has been cut off at the main since we left port, and obscure forms blunder and collide in the corridors and stumble down the staircases.

Other stories, of necessity, are written a while afterwards. Private Thomas Lyon was blown into the air and buried by a shell explosion, dug out and evacuated from the line. His extraordinarily vivid account must have been written at least two or three weeks later and probably more, but not much more. We had just reached the corner of the traverse when earth and heaven seemed to come together and to become one vast tongue of leaping flame; I felt myself falling through space and was conscious of a shattering roar.

In all cases, I have used only stories written by serving soldiers on or after 4 August 1914 and on or before 28 June 1919, the day that the Versailles Peace Treaty was signed. There is one caveat here: in a very small number of cases it is not absolutely clear whether a veteran, with a view to having his story published immediately post-war, has used his detailed diary and letters and, before publication, expanded on what he wrote at the time.

The scores of diaries and memoirs I have drawn on include unpublished sources, but also many that were published during the war years as well as a number of books published In Memoriam, either during or shortly after the war, in which letters from fallen officers were published by grieving families in an effort to pay tribute to their sons service and to leave a legacy for family and friends. These books offer the reader much that is often lost in memoirs produced many years later, not only their immediacy but a deeper insight: it is possible, for example, to appreciate the mood swings or variations in the temperament of a soldier. This subtlety is often lost in the smoothing out of emotions when a man reflects on his war from the comfort of the sitting-room chair. Ten years later he might write that he was exhilarated or depressed during an incident, but there is a qualitative difference between telling the reader that was how he felt, and the reader discerning this in the writing. There is also the problem of hindsight: reflecting on his experiences from the peaceful setting of his home, with the knowledge of victory won, a soldiers perception of his experiences might be influenced by his later life. He might be buffeted, too, by national events since the war: the Depression, the rise of Nazism and indeed the concomitant British anti-war movement or relatively recently, in the 1960s, the generally unfair maligning of the High Command. More parochially, a man might easily remember only what he wanted to remember, with the horror or the disaster not necessarily forgotten but put away in the back of the writers mind as too emotionally disturbing to be revisited. Of course, these events might not have influenced his recollections at all, but the possibility cannot be discounted.

I have always been a little wary of soldiers diaries and letters that were published during the war. Without close examination, I assumed erroneously as it has turned out that publishers would be keen to fall into step with the prevailing orthodoxy of the time for, logically, that would be commercially sensible. If the mood of the country was vehemently patriotic and against all things German, publishers would be likely to choose material which pandered to the buying publics instincts. If this were so, publications would tend not to challenge the reader either with the full horror of war or with the consequences of indecision or poor communication that would inevitably cost the lives of the men in the British front line.

In fact, these books are often astonishingly candid. There is a popular misconception that men traditionally spared their families back home the grim details of war, but that is not the case. When the suffering and the sense of loss were at the forefront of soldiers minds, they perhaps found solace in writing down their thoughts and their emotions; if tactical defeat resulted from inefficiency, this was not excised.