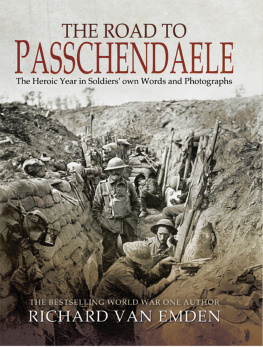

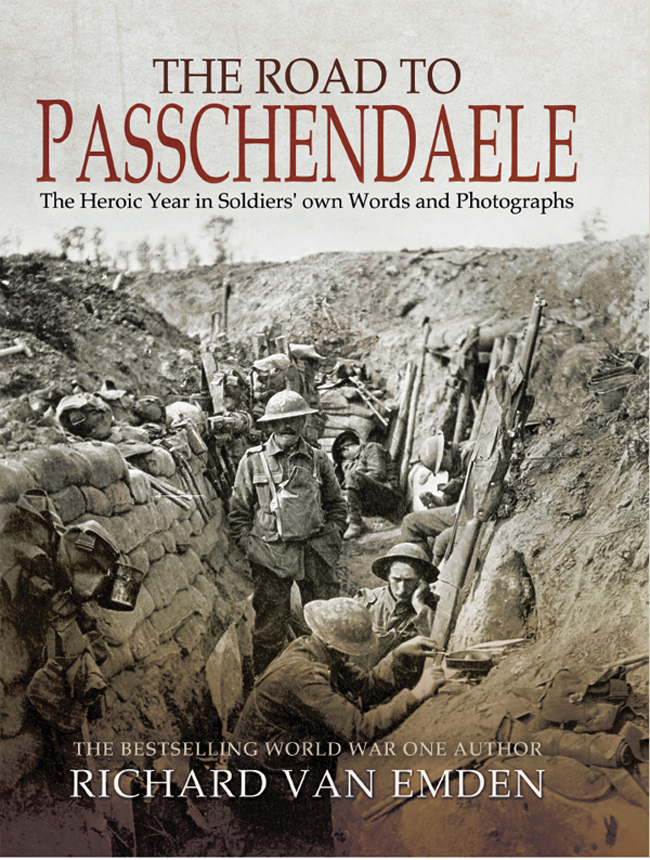

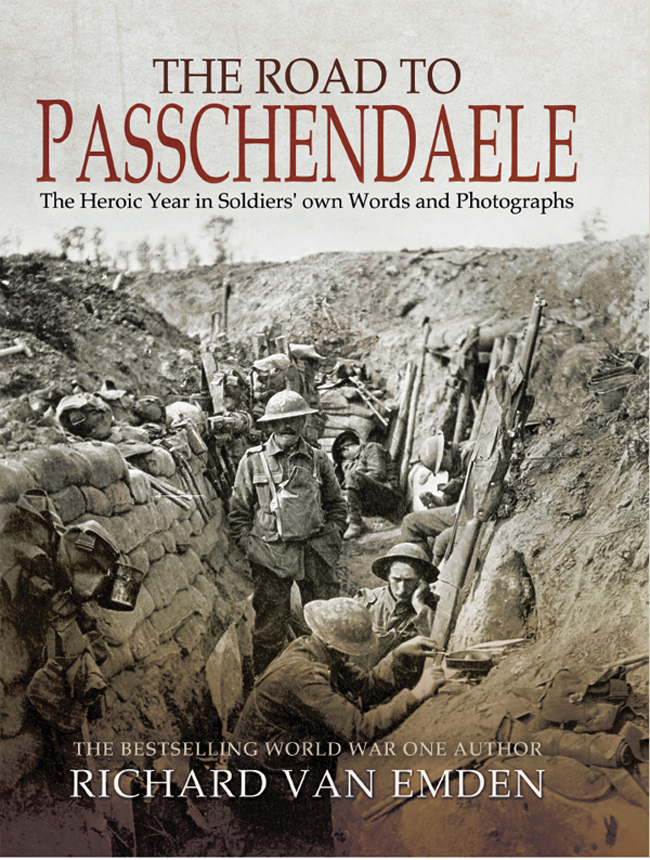

THE ROAD TO PASSCHENDAELE

THE ROAD TO PASSCHENDAELE

The Heroic Year in Soldiers own Words and Photographs

Richard van Emden

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Richard van Emden 2017

ISBN 978 1 47389 190 6

eISBN 978 1 47389 192 0

Mobi ISBN 978 1 47389 191 3

The right of Richard van Emden to be identified as the Author of this Work has

been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act

1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the

British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in

any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying,

recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without

permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology,

Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime,

Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport,

True Crime, and Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press,

Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Title Page: A private of the 3rd Worcestershire Regiment stares at the camera during the Battle of Messines, June 1917.

Frontispiece: Shell explosions during fighting, January 1917.

To

Linne Matthews

A piper of the 1/4th Seaforth Highlanders plays during a roadside break, July 1917.

Introduction

I was woken by a heavy trench bombardment and got up to see what it was. It turned out to be a half-hours strafe by the enemy of the brigade on our left, but as it was nothing to do with me I turned in again and finished my sleep.

Major Rowland Feilding, 6th The Connaught Rangers

B ack in the 1970s, Great War veteran Lieutenant Patrick Koekkoek was interviewed for a book on the Battle of the Somme. After publication, the author sent Koekkoek a complimentary copy but, after reading it, he remarked to his daughter that he did not like it. It wasnt like that, he said. This anecdote, recalled forty years later, was intriguing.

In any popular campaign history, the author is understandably inclined to flit from one part of the battlefield to another, to follow, in effect, the action: why dwell where nothing was happening? The technique is entirely valid and normally vivid, but the effect can be, albeit unintentionally, to give a skewed impression of carnage without end, of death and horror as a daily staple diet for men in the midst of a battle. That was what this former officer had objected to, not the veracity of assembled veteran recollections or the manner in which they were turned to prose. Koekkoeks memories were more nuanced than the collected wisdom of scores of men asked specific questions of a battle.

Mentally, men simply could not have survived without periodic lulls in the fighting. They needed rest in the line as much as out of it, even if that rest was continually interrupted. So, although engaged in a general offensive, if the fighting raged 2 or 3 miles away, soldiers learnt to switch off, at least in part. As the officer quoted at top of the page wrote to his wife from the trenches, in 1917, as it was nothing to do with me I turned in again and finished my sleep.

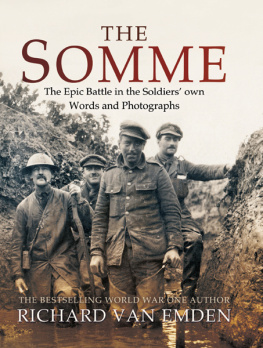

Stretcher-bearers and runners of the 3rd Worcestershire Regiment in a trench, Messines, June 1917.

And although the fighting ranged over many miles, sucking in hundreds of thousands of men, the majority of men serving on the Western Front were not directly involved. When the British Army numbered 2 million men in France and Flanders, the majority of them were in other, quieter parts of the line, perhaps recuperating and largely ignorant of an offensive elsewhere even though it might be audible. While writing this book about 1917, I have reminded myself not to forget the elsewhere.

Unlike 1916, a year during which British and Empire troops were involved in one campaign, 1917 was a year of four distinct offensives, two of significant duration: Arras (early April to mid-May) and Third Ypres (July through to November) and two short: Messines (June) and Cambrai (late November to early December). Given the number of offensives, it is surprising that the fighting of 1917 lasted, in total, just twenty-five days longer than that of the previous years Battle of the Somme.

Captain James Pollock VC, 5th Cameron Highlanders, near Ypres, July 1917.

Nevertheless, and with the benefit of hindsight, 1917 does appear to be a year of unparalleled misery on both sides of the line: an end to the war was nowhere near in sight, and popular enthusiasm for the struggle had long since eroded. There were high points for the British and Empire troops in 1917: the seizing of the Messines Ridge was an attack of extraordinary cunning and brilliant execution. The storming of Vimy Ridge by the Canadians on the first day of the Arras offensive was another notable moment, as too were the opening hours of the Ypres offensive on 31 July and the first days of the fighting at Cambrai when, in late November, long-silent church bells in Britain were rung in premature jubilation at success. But these moments did not lead to wider tactical success but rather to stalemate of one form or another. Vimy Ridge, for example, was the prelude to a further thirty-eight days of escalating attritional wretchedness in which British and Empire troops suffered 159,000 casualties, or 4,000 casualties on average a day by comparison, a third higher than those suffered on the Somme.

Interestingly, the casualties for the offensives of 1916 and 1917 are not radically different: 415,000 on the Somme, 475,000 for the combined attacks of 1917. What was different was the mindset of the men who undertook them. In the lead up to the Somme, even during the battle, there were still the vestiges of spirited optimism that a decisive blow would bring the war to an end, a view held by the Commander-in-Chief, General Sir Douglas Haig, for some considerable time during the offensive. By contrast, the struggles of 1917, particularly at Arras and Ypres, were characterized by a grim resignation to the necessity of attrition and gradual battlefield predominance in men and arms. British troops did not lack morale and most fully expected to win, but not by a stroke of battlefield mastery. All in all, 1917 completed the transition to the wearing out war. And, perhaps for the first time, the soldiers began to question the competence of their most senior commanding officers, as one long-serving company quarter master sergeant wrote of the fighting at Ypres in September 1917: