About the Book

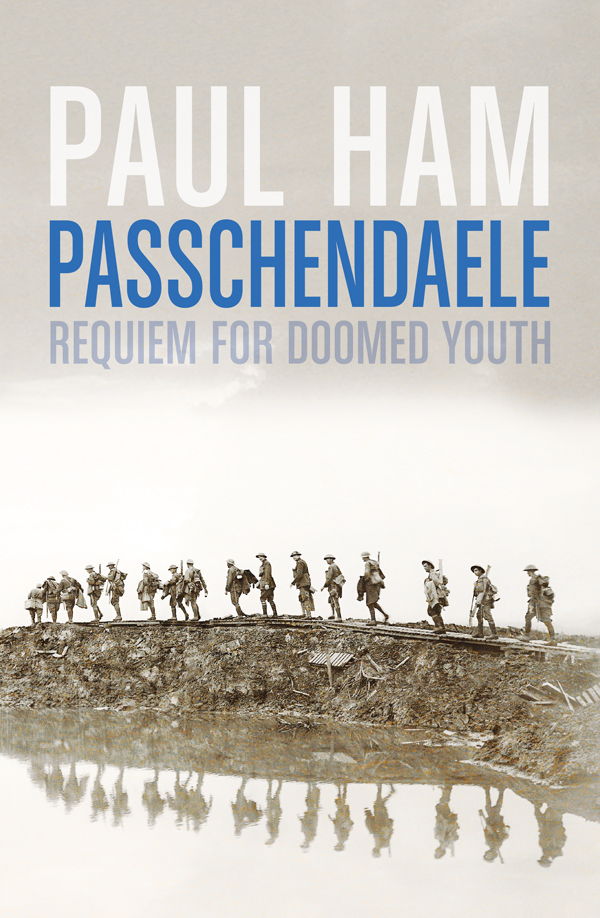

Passchendaele epitomizes everything most terrible about the Western Front. This battle was fought from July to November 1917, during the worst year of the war for Allied morale: images of blackened tree stumps rising out of a field of mud, corpses of men and horses drowned in shell holes, fraught soldiers huddled in trenches awaiting the whistle.

The intervening century, the most violent in history, has not disarmed these pictures of their power to shock. At the very least they ask us, on the 100th anniversary of the battle, to try to understand what happened here. Yes, we commemorate the event. Yes, we adorn our breasts with poppies. But have we understood?

What happened at Passchendaele was pure attrition, a wearing down war at its most concentrated and ferocious. Paul Hams Passchendaele: Requiem for Doomed Youth shows how men on both sides endured, with a very real awareness that they were being gradually, deliberately, wiped out.

Yet neither side broke. The British, Anzac and Canadian forces went over the top, again and again, to their likely doom. The Germans were ordered to sit in the path of this storm of steel. And if they fell in such combat, they became, as the commanders described them, casualties in the normal wastage.

The soldiers family remembered him as the son, husband or brother before he had enlisted. By the end of 1917 he was a different creature: his experiences on the Western Front were simply beyond their powers of comprehension.

The book tells the story of ordinary men in the grip of a political and military power struggle that foreshadowed the destiny of the world for a century. Passchendaele lays down a powerful challenge to the idea of war as an inevitable expression of the human will, and examines the culpability of governments and military commanders in a tragedy that destroyed the best part of a generation.

INTRODUCTION

THEY CLAIM A SMALL PLACE in our minds, a century on, in memorial services and on poppy days. We are the dead, they announce in the poem In Flanders Fields, like regiments of ghosts whose spirit wont rest. More than half a million of them lay dead, wounded or missing on those fields in 1917, mostly British, Australian, Canadian, Irish, New Zealanders and their German counterparts, a few of whose voices survive in letters and diaries. They tell of one of the bloodiest battles of the Great War indeed, of any war with fear and love, humour and pathos, and sometimes with a kind of urgency, as if conscious that theirs would be the only eyewitness accounts of Passchendaele.

The Flemish town that bears this name seems unable, or unwilling, to carry the burden of what happened here. The local spirit is more inclined to look forward than back: there is no general monument here. The historical and emotional freight is probably too heavy for one small community, let alone a city or country. (The larger, neighbouring town of Zonnebeke hosts the new Passchendaele Museum.)

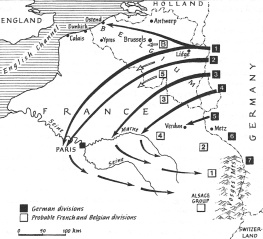

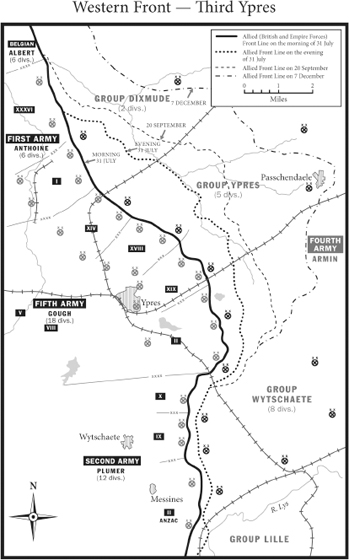

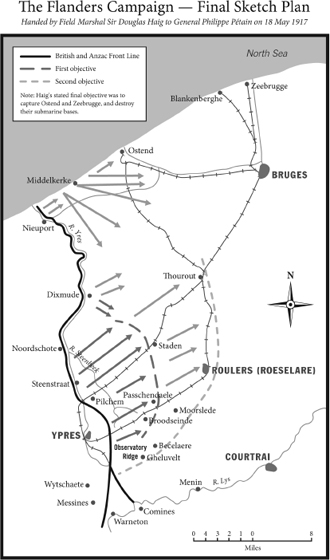

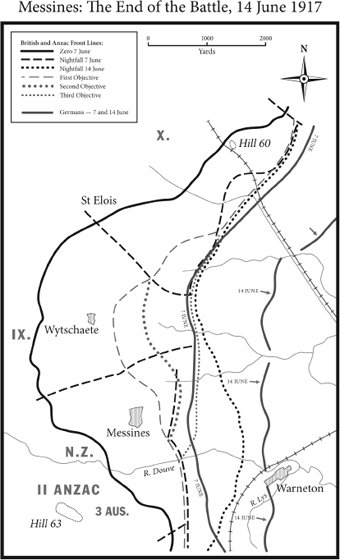

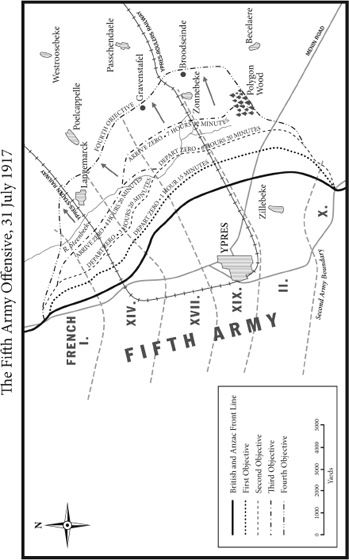

Officially they called it the Third Battle of Ypres, or Third Ypres. In fact, it was a series of immense clashes on the plains to the east of the mediaeval city of Ypres, between 31 July and 11 November 1917. The people and the press fastened instead on the village at the heart of these events, five miles north-east of Ypres: Passchendaele, a word evoking Easter and the Passion of Christ (from the Latin verb pati , to suffer). Here, the word suggests, lies more than a little Flemish community; here lies a dale of martyrdom, a soldiers Calvary, a land of tortured souls.

This is what Passchendaele has come to mean in the civilian mind: an epic of pointless butchery that, even by the standards of the Great War, entered the realm of the infernal and monumentally futile. Soldiers, animals, artillery and pouring rain were thrown together in a maelstrom of steel and flesh in the name of a strategy that anticipated hundreds of thousands of casualties and all for nothing.

Some military specialists disagree with this popular view of Third Ypres, arguing that most of its battles were necessary, achieved some of their goals and were worth the cost. For these self-described revisionists, Passchendaele was part of a just and inevitable war against tyranny, and not another massacre in an avoidable tragedy that destroyed the best part of a generation (we shall address this endless controversy in ).

We may be sure of one thing: the huge casualties were not some epic blunder; they were expected, they were planned for . To understand why is to understand the meaning of a total war of attrition. That effort may be more than the twenty-first-century mind can bear, living as we do in the super-sentimental West, where a body bag is treated as a political opportunity. Many of us approach the Great War not through primary historical records but through the lens of literature, films, photographs or the entertainments of Blackadder and Oh! What a Lovely War , cultural phenomena that soften, ridicule or set at one remove the truth. That is not to demean these interpretations. It is to say that the finest war literature, some of the funniest satire, and the work of cultural historians such as Paul Fussell, Jay Winter and Modris Eksteins, have transformed the perception of To borrow the famous Platonic metaphor, that is to look at the War as a shadow thrown against the wall of a cave, the shadow of its true Form.

To open our minds to this tragedy, to understand what happened in Flanders in 1917, is to turn our eyes from the shadow and gaze at the Form. It means journeying into a different world, a kind of hell, no doubt, but also a realm in which people lived at extremes, captive to the emotions of hope, love, terror and hubris. The journey is hard and horrifying, and yet also profoundly moving. The following symphony of witnesses, gathered into a narrative, will tell us something of the truth of Passchendaele, and something of the political imperative that drove humanity to that terrible place. Stay the distance and we shall meet on the other side, with a deeper understanding of what human beings are capable of doing to their fellow creatures, and why. For only by reasoning why can we hope for a wiser, perhaps kinder, future. My conclusions, some of them novel, appear in ; for now, we shall confine ourselves to the narrative.