Introduction

Objective reached but am afraid is not fully consolidated. The mud is very bad and our machine guns are filled with mud, wrote Capt T.W. MacDowell, OC B Coy, 38th Battalion Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), to his commanding officer, Lt-Col C.M. Edwards, at 0800hrs on 9 April 1917. MacDowell would win the Victoria Cross for his conduct during the battle of Vimy Ridge.

I have about 15 men near here and can see others around and am getting them in here slowly ... The runner with your message for A Company has just come in and says he cannot find any of the Company officers. I dont know where my officers or men are but am getting them together. There is not an NCO here. I have one machine gunner but he has lost his cocking piece off the gun and the gun is covered with mud. The mens rifles are a mass of mud, but they are cleaning them. My two runners and I came to what I had selected previously as my company HQ. We chucked a few bombs down and then came down. The dugout is 75 feet down and is very large. We explored it and sent out 75 prisoners and two officers. This is not exaggerated as I counted them myself. We had to send them out in batches of 12 so they could not see how few we were. I am afraid few of them got back as I caught one of them shooting one of our men after he had given himself up. He did not last long and so am afraid we could not take any back except a few who were good dodgers as the men chased them back with rifle shots ... the ground is almost impassable. Horrible mess. There are lots of dead Bosche and he evidently held well ... The line is obliterated, nothing but shell holes ... Please excuse writing.

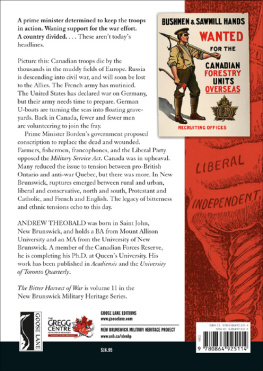

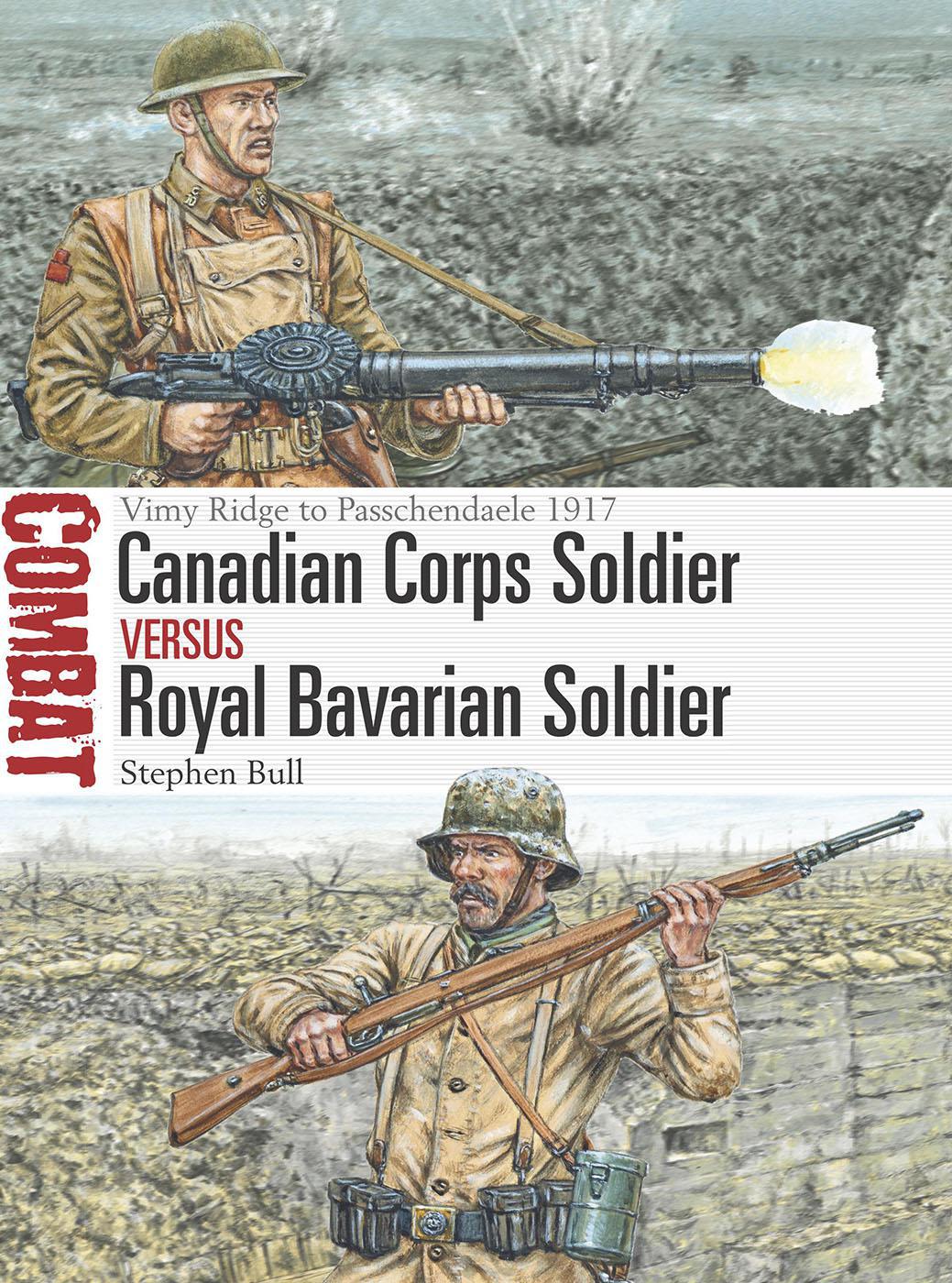

The year 1917 saw a series of battlefield encounters leading ultimately to surprising results. Within the framework of World War I they brought to a climax clashes between the fighting men of an ancient kingdom of southern Germany, since 1871 subsumed into the German Empire, and those of a Dominion of the British Empire. Neither side initiated this collision, nor was it necessarily recognized by the troops: Bavarian soldiers often referred indiscriminately to any khaki-clad enemy as English or Tommies. Frequently they were correct, as many Canadian soldiers were British-born. Canadians usually regarded this particular enemy as the Kaisers Germans first, and, if they made any distinction, Bavarians a poor second. Yet arguably the bloody clashes of the foot soldiers of empires in 1917 helped usher in historic changes far beyond the battlefields of France and Flanders.

Over the top Canadians demonstrate their fighting spirit in training. Though greatcoats were not usually worn in the assault, much of the other kit is typical: steel helmets, Short Magazine Lee Enfield (SMLE) rifles with fixed bayonets, Pattern 1908 webbing, and additional ammunition bandoliers.

Despite extensive fighting against Turks and Bulgarians at Gallipoli, Salonika and in several corners of the Empire, British grand strategy at the end of 1916 remained locked to the fate of France, and to hanging grimly on to the remaining sliver of Belgium. The attritional struggle of the Somme had cost all sides dearly, with Britain taking more of the front from the French as her armies expanded. Victory of a sort was claimed by all protagonists, with heavier losses to Entente forces offset by damage to a German Army which was less able to find reinforcements, and its subsequent withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line. With Russia suffering reverses against Germany in 1916 and Romania invaded, but with France now recovering from the bloodbath of Verdun, it appeared inevitable that Britain and the Canadian Corps would be called upon to attack again.

Bavarian beer also nurtures heroes: NCOs and men of K.B. 7. Infanterie-Regiment Prinz Leopold on a station platform ready for departure to the front, 1915. The regiment was one of the three committed to battle at Fresnoy-en-Gohelle in May 1917.

On the other side of the line such an offensive was already anticipated, though not its location. Preparations were made accordingly, as noted by Chief of the General Staff, Paul von Hindenburg,

Not the least important of these measures were the changes we introduced into our previous system of defence ... In future our defensive positions were no longer to consist of single lines and strong points but a network of lines and groups of strong points. In the deep zones thus formed we did not intend to dispose our troops on a rigid and continuous front but in a complex system of nuclei and distributed in breadth and depth. The defender had to keep his forces mobile to avoid the destructive effects of the enemy fire during the period of artillery preparation, as well as voluntarily to abandon any part of the line which could no longer be held, and then to recover by counter attack all the points that were essential to the whole position. These principles applied in detail as in general. (Hindenburg 2005: 261)

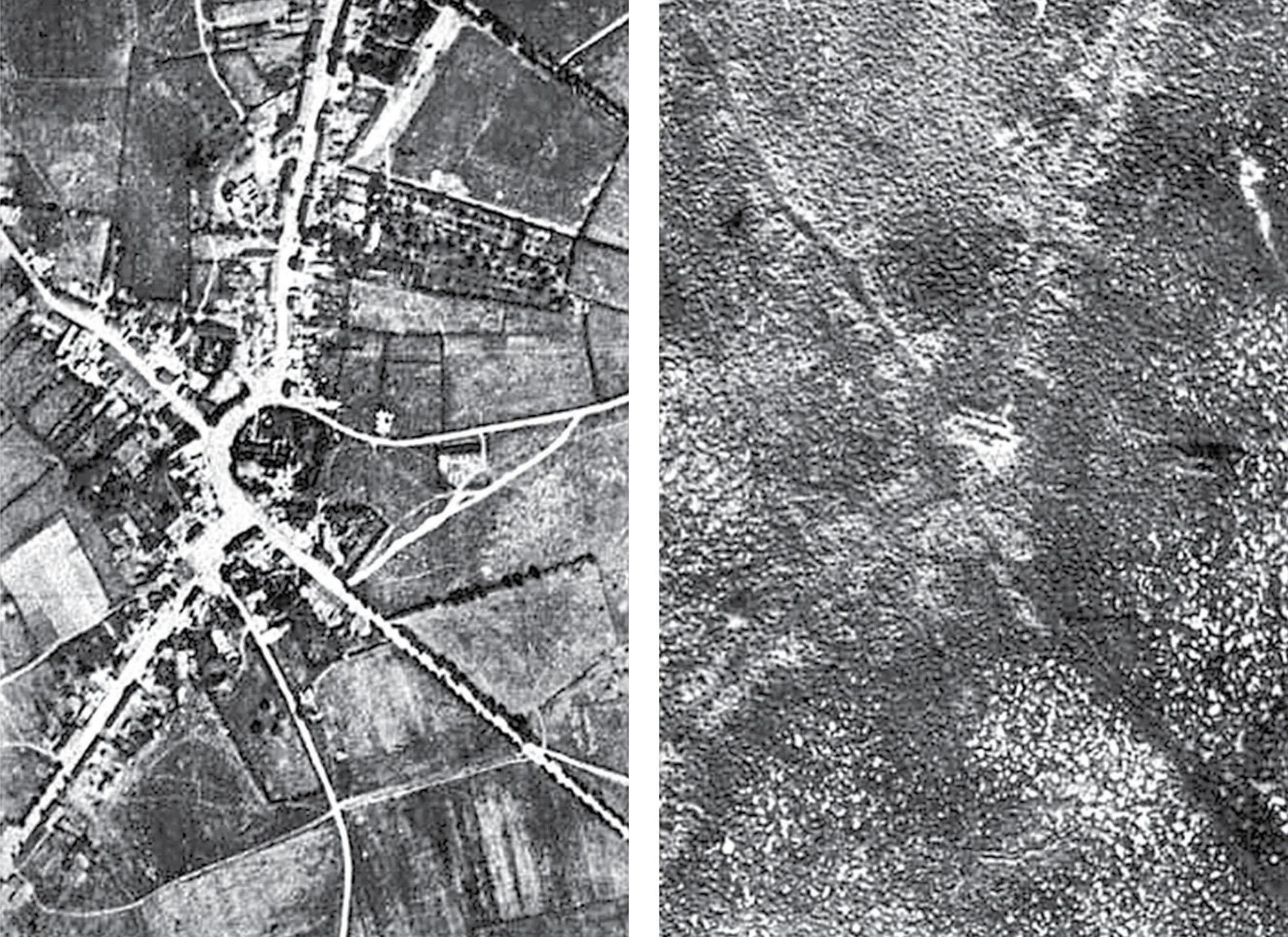

Passchendaele, an inconsequential village just 165ft above sea level and barely 50ft above surrounding terrain, was the epicentre and ultimate target of two battles within the Third Ypres offensive. These photographs show Passchendaele village from the air, before and after the battle. The outline of the church and shadow of the road system remain visible, but every dot is a waterlogged shell hole.

By early 1917 the Canadian and Royal Bavarian contingents had been through much heavy fighting, and garnered good reputations among British and German Imperial forces. Both suffered heavily and gained experience accordingly, though it was the Bavarians who had sacrificed the most. The year would prove crucial in terms of the development of infantry combat in an increasingly grim struggle on the Western Front. The previous year the Somme and Verdun had pushed home hard lessons either side of the line. Where once defensive positions were linear, now there were deep zones. Where trenches once reigned supreme, tacticians were beginning to think in terms of resistance nests, strong points and webs to catch and slow enemy advance, with shell holes and bunkers crucial to the scheme. Holding one specific trench to the death with concentrations of troops had given way to progressively lighter trench garrisons, greater numbers of machine guns and more sophisticated methods of counter-attack. Bombardments, blunt instruments in 1915, developed into complex fire plans with an emphasis on timing, surprise, creeping barrages, different types of shell and fuse, and the neutralizing effects of different gases.

The infantry attack also developed to accommodate new conditions. Battalions were now often arranged in depth so that companies were committed one or two at a time, and less as linear waves. The spear-point of the assault might rest on specific platoons or shock troops. Commanders were encouraged to think more in terms of topographic detail providing cover from fire, dead ground and chinks between bombardments, and even attacking into the bombardment rather than regarding artillery as separate from the infantry battle. Attempts were made to cross defensive zones swiftly, sometimes with only very brief bombardments, occasionally with none at all. Attack in darkness, at dawn, or behind smoke was now normal. New weapons and mixes of weapons within platoons were introduced on both sides of the line. Lewis guns, already significant players, were now challenged by the MG 08/15 machine gun and sections were arranged within platoons to field particular weapons or undertake specific tasks. Vickers machine guns, now the province of the Canadian Machine Gun Corps, not only provided machine-gun barrages, but were added back into advances as immediate support to attacking battalions.