Contents

There have been many descriptions of the German Army in the Second World War: most published since 1945 with the benefit of hindsight and often little idea of how information was gathered. This obscures the crucial point that during the conflict obtaining up-to-date material on the enemy was extremely difficult, while producing authoritative documents for use by British and US forces was a potential matter of life or death. A wary enemy kept as much as possible secret, and in a fast-moving war what was accurate today was frequently out of date by the time it had been published in a form accessible to the fighting soldier. This cycle of collection, analysis, processing and dissemination might take months, and sifting the wheat from the chaff was as much an art form as a science. As a result the fog of war applied just as readily to military intelligence as it did to the battlefield, and manuals and bulletins flowed thick and fast in an effort to keep up.

What is attempted here is a snapshot of the work of intelligence, as well as of its target. For if the German Army was dynamic, moving and developing from campaign to campaign, so also was its shadow, the series of time lag images produced by those who sought to capture its character, strength and collective state of mind. What is replicated in the following chapters is not therefore just one intelligence manual of the German Army, but a collection from different publications, both US and British, created over the course of the war, plus a sample of the source documents and illustrations with which intelligence officers had to work. Some of the pictures painted by the Allies were full, detailed and pretty accurate; others sketchy and episodic, occasionally coloured by preconceptions or a desire not to leave a daunting impression of technical excellence or cause the discouragement of the reader.

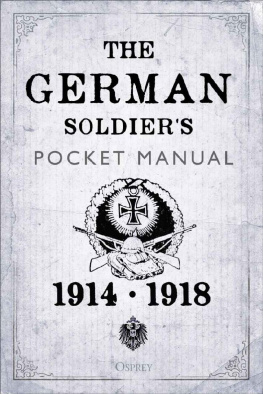

British General Staff Handbooks of the German Army, first produced well before 1914, were revised during the First World War and supplemented by many different types of manual and, from 1917, the complementary output of the US War Department, which had German documents translated and edited at its Army War College. By the end of the First World War the US Military Intelligence Division alone numbered more than 1,500 personnel, officers, agents and civilian staff. Intelligence officers were also attached to military units in the field, down to battalion level.

Sadly much was unlearned in the inter-war period, and by 1936 the US Military Intelligence Division numbered fewer than 70 people. Despite subsequent expansion of the various intelligence organisations the success of the Signal Intelligence Service in cracking the codes of the Japanese Purple cipher machine in 1940 was not replicated in efforts aimed at Germany. Initially the British had scarcely better fortune. In 1936 a Z organisation for running agents in Germany and Italy was formed under Claude Dansey at Bush House on the Strand. Agents were dispatched to 12-Land, their code for Germany, and at least a handful of anti-Nazi Germans were turned to work for the UK. One young British officer, under cover of working for a film company, toured Austria and Germany with the brief of creating an Order of Battle. Yet overall impact was limited, as were the efforts of personnel embedded in embassies, overwhelmed by work which included processing passports for would-be migrs.

From September 1939 Britain was at war with Germany. The US, which was not, maintained a diplomatic presence; moreover, American journalists retained freedom to report from inside the Third Reich. Some of these reporters were of German ancestry and fluent German speakers. In one remarkable example Louis P Lochner accompanied German forces during the invasion of the Low Countries and France, returning ambivalent copy juxtaposing reports of sentimental child-friendly German soldiery with the burning of Louvain library and all the horrors of modernest [ sic ] warfare. With the outbreak of war between the US and Germany in December 1941, Lochner and 137 other newsmen were interned at Bad Nauheim, but were repatriated five months later.

The establishment of the Secret Intelligence Service communications war station at Bletchley Park early in 1939, good relations with Czechoslovak and Polish intelligence, relocation of Z to Switzerland and the formation of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) all gradually improved British military intelligence gathering. In early 1940 a team including Alan Turing, working under Alfred Knox, built on earlier Polish efforts to crack the Green key of the German Army Enigma code. Later the same year Britain and the US moved towards full exchange of cryptographic information, and in America Wild Bill Donovan was promoted COI or co-ordinator of all forms of intelligence, and subsequently to head the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Despite rivalries, significant amounts of information were shared, not least about German forces and their dispositions.

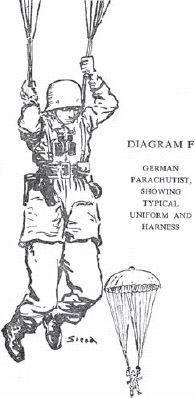

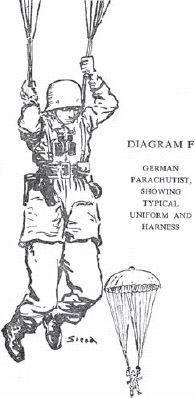

A rough sketch of a German parachutist from Home Guard: A Handbook for the LDV , 1940. Early expectations were that Local Defence Volunteers would confront enemy airborne troops, but these patriots had a nasty habit of shooting at anybody dangling from a parachute. As a result illustrations like this, and instructions to open fire only when the number of jumpers exceeded the number of men in a bomber crew, were issued in mainly to save British pilots.

In 1942 the US Military Intelligence Division reorganised so that it no longer performed operational functions, but acted as planning and policy maker, co-ordinating the efforts of the US Army and Navy. The US Army itself now fielded three intelligence organisations: the Military Intelligence Service, the Signal Security Agency and the Counter Intelligence Corps. From March 1942 the Military Intelligence Service was tasked with the production of intelligence on the Germans for use by front line commanders. The organisation was then headed by Brigadier-General Hayes Kroner, who had served in London as a military attach during 1934 to 1938, as observer in England early in 1941 and with the British Empire section of the Intelligence Branch.

While operational intelligence on the German Army was gathered through a variety of means including decryption, espionage, battlefield observation and aerial photography, a surprising volume of material was obtained by far less dramatic means. Conflict zones were scoured for equipment, and prime items such as new tanks, guns and shells were hauled off to specialist facilities to be painstakingly disassembled, analysed, tested, measured, weighed, photographed and reassembled, then tested again, sometimes to destruction. Prisoners were also an important source of information, but there was much more to extracting material than interrogation, with or without bribes or threats.

Open publications were scoured by Allied intelligence and enemy propaganda was replete with photos like this example from a 1943 periodical, showing a German soldier armed with an MP 40 sub-machine gun wearing tank destruction arm badges. Problems arose when the enemy issued images of rare or fanciful items or exaggerated specifications.