CONTENTS

Introduction

To a large extent, the outcome of World War II depended on amphibious landings. Without the ability to put masses of troops, vehicles, and equipment on contested shores, and to establish exploitable beachheads there, the Western Allies would not have been able to reclaim conquered territories in the Pacific, North Africa, and Western Europe. In short, without amphibious landings much of the conflict would have remained in stalemate, rather than Allie d victory.

In this fact there is some cause for disquiet, because amphibious landings rank among the most challenging of military operations, with highly uncertain outcomes. Consider the perils and problems facing Allied amphibious forces embarking on any landing operation. They first had to find suitable landing zones, ones that were not only hydrographically and geographically amenable to putting ashore tens of thousands of troops, but which could also cope with the endless conveyor-belt of logistics that would roll in subsequently to sustain the offensive momentum. Then the planners and commanders not only had to devise ways to keep the landing location secret from the enemy not easy when you are putting together a vast naval, air, and land force (total troops put ashore in Normandy on June 6, 1944 numbered 156,000) but also how to overcome the defenses the enemy had in place along the landing zone, defenses that were often purposely and intelligently devised to prevent just the sort of amphibious landing the planners were intending. To deliver the invasion, the elements of the landing force had to be transported effectively by naval assets from their home bases to the staging waters just offshore, then from that position to shoreline, all to schedule. Troops had to hit the beaches with enough firepower and momentum to overcome shoreline and beachhead resistance, even as waves of subsequent landing forces piled onto the beach, threatening organizational chaos. Now came one of the most complex factors of an amphibious landing: logistics. The combat loading of supplies aboard the landing craft had to be intelligently ordered to meet the evolving tactical needs of the troops ashore, and the efficiency of offloading and storage had to be of clockwork precision. All this was conducted in the teeth of the active resistance of the enemy, who would bring all the firepower assets they had from major coastal artillery pieces to automatic small arms to bear on a relatively small patch of land choked with a wealth of target oppo rtunities.

June 1944: German coastal batteries fire on Allied forces landing in Normandy in the area at the mouth of the Orne River. This photograph shows the typical combination of defenses around the Normandy landing zones, with intensive tiers of beach obstacles overlooked by multiple firing positions and strongpoints in the bluffs and cliffs above. (ullstein bild/ullstein bild via Getty Images)

Given these challenges, it is little short of remarkable that all the major Allied amphibious invasions in Europe were successful. (Dieppe, on August 19, 1942, could be viewed as an exception, but that action was a raid rather than an invasion.) This outcome is indicative of the fact that although the defenders against amphibious assault were certainly in a theoretically strong position, there was also much weighted against them. For a start, the invaders would conduct exhaustive pre-invasion reconnaissance and planning, identifying all defenses and working out exactly how to overcome them with every firepower asset at their disposal. The defenders would also, typically, be numerically inferior to the landing forces; given the breadth of Germanys operational commitments, particularly on the Eastern Front, it was impossible to keep huge numbers of men tied up and inactive in coastal positions, just on the off-chance of a landing. Therefore, Germanys coastal defense policy was, by and large, made up of two strands: first, to establish physical coastal defenses that could be manned by limited numbers of troops (the Atlantic Wall system is the most significant expression of this policy); and second, to retain mobile forces inland that could react to identified landings, and deploy them rapidly to the landing area to quash the beachhea d buildup.

In this book, we will see both strands of German coastal defense policy in action, and equally their failure. At the same time, we will also see the strengths and weaknesses of Allied amphibious warfare tactics under a harsh spotlight. Amphibious landings, indeed any military operation, always have a significant degree of disorder or friction, and in the battles explored here, we see the human consequences of this chaos, often bloodily expressed on the shoreline.

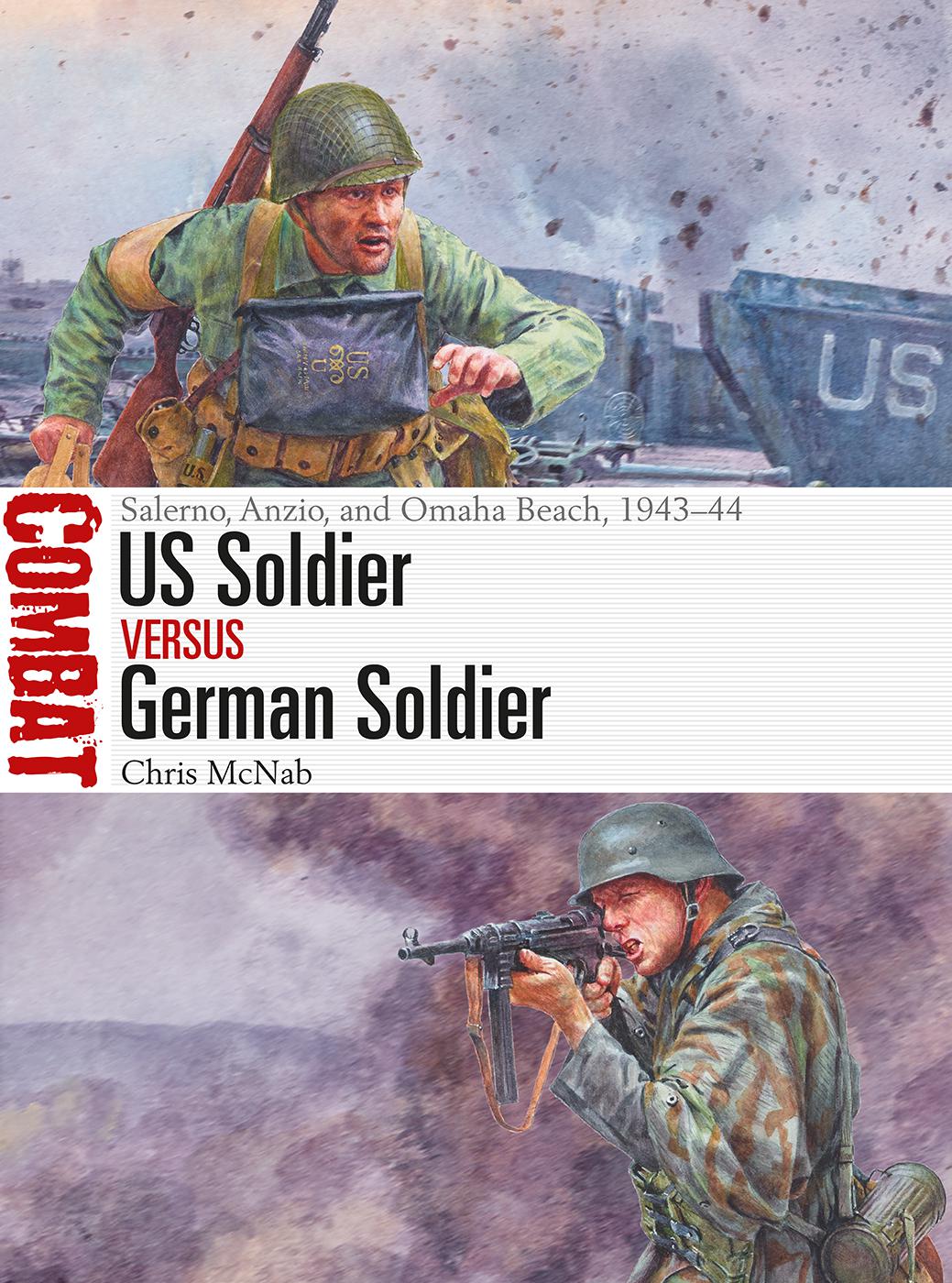

Accordingly, we will study the front-line combat in three major amphibious actions: Operation Avalanche the invasion of mainland Italy at Salerno on September 9, 1943; Operation Shingle the subsequent landings in Italy at Anzio on January 22, 1944; and Operation Neptune / Overlord specifically, the Omaha Beach landings on June 6, 1944, as part of the Allied invasion of Normandy. All these actions have been studied extensively in other Osprey publications, especially the respective Campaign titles. Here, therefore, we will narrow our focus tactically. From the US side, our principal attention is on the US Armys combat engineers. The role of combat engineers in an amphibious landing was crucial. Not only were they largely responsible for clearing the major enemy beach defenses (a task that required them to be in the very first waves of the assault landings), but they would also have to perform a daunting range of tactical and logistical tasks thereafter, from laying beach roads to managing casualty evacuation. Without the combat engineers, amphibious landings would scarcely have been possible.

Major Allied amphibious actions, March 1942August 1944

MAP KEY

March 28, 1942: Operation Chariot British amphibious Commando raid against the German dry dock at Saint-Nazaire, France.

August 19, 1942: Operation Jubilee Allied (predominantly Canadian) amphibious raid against the German-occupied port of Dieppe, France.

November 816, 1942: Operation Torch major Anglo-American invasion of French North Africa, opening a second front and providing a steppingstone to the later invasion of southern Europe.

July 910, 1943: Operation Husky Allied (mainly Anglo-American) invasion of Sicily, opening a new front in southern Europe and a jumping-off point for the invasion of mainland Italy.

September 3, 1943: Operation Baytown British and Canadian invasion of the southern toe of Italy, as part of wider Allied invasions of mainland Italy and an effort to draw German forces away from Operation Avalanche .

September 9, 1943: Operation Avalanche major Allied amphibious landing south of Naples in the Gulf of Salerno, designed to seize Naples farther north and to trap German forces in the south of Italy.

September 9, 1943: Operation Slapstick British amphibious landing around Taranto, aimed at seizing the ports of Taranto and Brindisi and providing another foothold in southern Italy for Allied troops.

January 22, 1944: Operation Shingle Allied amphibious landing around Anzio and Nettuno in western Italy, intended to outflank German defensive lines inland.

June 6, 1944: Operation Neptune / Overlord Allied invasion of German-occupied France along the beaches of Normandy; opening of the Second Front in Western Europe.