CONTENTS

To Rick Lippiett, always aspiring to Faramir, ever ending up Boromir.

Introduction

In the lines around Verdun during those first bitter weeks of January 1916, the fury and immense loss that characterized the battles of 1915 seemed rather far away. The ferocity of the Great War the war to end all wars had left the fortress city and its environs more or less alone, with initial German advances on the River Meuse turning Verdun into a salient, but not attacking towards the ci ty itself.

The positional stalemate that had developed all along the Western Front in the previous 15 months was an aberration. Generaloberst Helmuth von Moltke (aka Helmuth the Younger), the Chief of the German General Staff who led Kaiser Wilhelm IIs armies in the first few months of the war, was well aware of the danger his nation faced if it were forced to fight enemies on several fronts. His plan was to employ a version of the traditional Prussian Vernichtungsstrategie (strategy of annihilation) in the West that would crush France in a matter of weeks or months at most (echoing his uncle Moltke the Elders glorious campaign of 1870 during the Franco-Prussian War), and which would then allow the German Army to redirect its entire focus eastward to confront what Moltke and his staff saw as the main threat to Germany: Imperial Russia. Unfortunately for Moltke the Bewegungskrieg (war of movement) that he had envisaged for the German right hook that would smash through Belgium and envelop the French left flank was compromised; logistical logjams meant that the attack timetables, already unfeasibly tight, could not be kept to; in addition, Moltkes own removal of much-needed troops from the main attacking force to bolster other arguably less-important fronts weakened the strength of the German attack at its most crucial point; and finally there was the unexpectedly stubborn resistance of the French Army and its allied British Expeditionary Force at the Battle of the Marne on 612 September 1914. The sum of all these factors saw Moltkes great attack first stutter and then stop, ground down into the bloody mud of Fren ch fields.

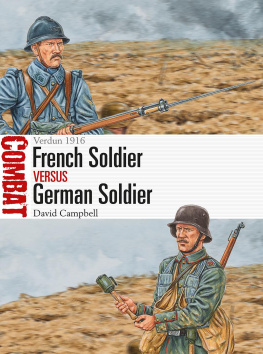

A column of German troops in marching order move towards Verdun, February 1916. In the weeks leading up to the German attack, 5. Armees army corps (VII. Reservekorps, XVIII. Armeekorps, III. Armeekorps and XV. Armeekorps) were positioning themselves to the north of Verdun on both banks of the River Meuse, supported by over 1,200 artillery pieces. Despite such apparently overwhelming German firepower, it would be up to the infantrymen to take the battle to the enemy, their path hopefully eased by artillery barrages and the actions of the Stotruppen (shock troops). (Maurice-Louis Branger/Roger Viollet via Getty Images)

A group of French infantrymen pose for a photograph, 1918. The uniforms, weapons and equipment shown here are much the same as those used at Verdun. The man on the left holds the CSRG Chauchat, the automatic rifle that would see its first use in April 1916 (minus the flash-hider that would only start to appear in 1917), while the man next to him carries the Vivien-Bessires rifle grenade launcher, also introduced in 1916; the others have Lebel rifles and one man sports a pair of Billant F1 hand grenades. Several of the men also bear gas-mask tins: the one-piece M2 gas mask had to be folded for storage in the tin, something that often caused damage to the rectangular viewing panel on early versions of the masks, so a redesigned M2 gas mask in different sizes and with separate round eyepieces was issued from April 1916. (Photo12/UIG/Getty Images)

On 14 September Moltke was succeeded by General der Infanterie Erich von Falkenhayn, a man with the Kaisers favour (curried during Falkenhayns tenure as the Prussian Minister of War) but little influence within the German General Staff where, due to his years of foreign service in China, he was something of an unknown quantity. For Falkenhayn on the Western Front the British were the ultimate enemy to be defeated they were presumed to be the most unremitting and aggressive of Germanys enemies, and the least likely to accede to an ending of the war on German terms. Unfortunately, the defensive positions held by Britains armies, combined with their perceived strength (seen as comparable to German forces in many ways), made an attack on them unlikely to be successful enough to drive them out of the war. The French Army, however, was an easier prospect: mauled in the battles of 1915, large numbers of captured deserters had reinforced German perceptions about French war-weariness, the parlous nature of the French military infrastructure, and the brittle nature of Fren ch morale.

French infantry prepare to move up the line during the battle of Verdun, 1916. Unlike the German Army, which would leave its infantry divisions in the line, the French Army (under Gnral de division Philippe Ptains initiative) would regularly rotate its infantry divisions out in order to allow them to recuperate, bringing in fresh formations to replace them. (Archive Photos/Getty Images)

A line of German prisoners, Verdun, 1916. Imprisonment offered captured soldiers a chance to see the war through the enemys eyes, one such case being a half-composed letter to his mother taken from Feldwebel Karl Gartner, a Pomeranian soldier of Infanterie-Regiment 243 who was captured near Fort Vaux in late March: our losses are more terrible than I understood. I have just met Ludwig Heller, my comrade in the 29th. He is in charge of the burial parties and gives me terrible news of the scenes of carnage which took place in front of Vaux and Douaumont we have been badly informed by our officers. We are just maintaining our positions on the ground we have won after fearful losses and we must give up all hope of taking Verdun The war will continue for an indefinite period, and in the end there will be neither victors nor vanquished (quoted in Dugard 1917: 26869). (Courtesy of Brett Butterworth)

Falkenhayn saw the repeated French failure to break through German defences as confirmation of his assumption about the state of Frances armies, namely that they were deficient in morale, operational acumen, and were also nearing exhaustion through losses of men and matriel . Such a view was underpinned with Falkenhayns general prejudice (not uncommon in pre-war Germany) about the French national character coupled with that nations perceived political and economic decline, which were seen to be in stark contrast to the morally robust and industrially ascendant Germany (Foley 2005: 18485). To crush the French would in turn cripple Britains capacity to continue the war, knocking Englands best sword out of her hand in Falkenhayns memorab le phrase.

German plans for 1916 would centre around the French positions in the Argonne in north-eastern France. The overarching approach was one of Ermattungsstrategie (strategy of attrition), drawing the French into a battle that would necessitate their commitment of ever-greater numbers of front-line and reserve troops, eventually forcing the British to support them in a similar manner. Such an approach would be so ruinous that it could force the French and British to the negotiating table; and even if it did not, with the armies and reserves of her two enemies thus ground down by attrition, the German Army could then launch a major offensive of its own and break through the weakened Allied lines. To be successful such a strategy required the German Army to maintain a suitable reserve, which in turn would define one of the most characteristic elements of the campaign the reliance on enormous numbers of artillery pieces to do the hard work of obliterating the French Army, saving the men for later offensives. The French would have to take the bait, of course, which meant picking a target the loss of which would be too wounding for French pride to countenance: the ancient and much-vaunted fortress city of Verdun.