An assured work which steps well beyond the narrow and constricting boundaries of military history. Altogether more significant than a mere dry account of a battle of attrition would have been. Harrowing.

A story that still has the power to shock and horrify. Consistently intelligent and readable. An engaging and important book.

Ousby vividly brings the horrors of battle to life using the personal accounts of ordinary people who fought at Verdun.

A brilliant study a tender and beautifully worked reappraisal of the battle and the implications of Verdun.

A triumph. A must for any modern world history buff.

A splendid account. Informed and erudite, lucid and sanguinary.

CONTENTS

PART ONE

PART TWO

PART THREE

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

The months are not long nor the days nor the nights. Its the war that is long.

Guillaume Apollinaire

War destroys any conception of goals, including any conception of the goals of war. It even destroys the idea of putting an end to the war.

Simone Weil

PROLOGUE

T HE R OAD TO V ERDUN

Everyone came to Verdun as if to receive some ultimate recognition there; as if all the provinces of the patrie had needed to join in one particularly cruel and solemn sacrifice among the sacrifices of the war, exposed to the worlds gaze. They seemed to go up the Voie Sacre like some new form of offertory, to the most formidable altar that mankind had ever raised.

Paul Valry, Rponse au remerciement du Marchal Ptain

lAcadmie franaise (Reply to the Speech of Thanks

by Marshal Ptain in the Acadmie Franaise), 1931

Across the valley they could make out the ghost of a town in the smoke.

The air trembled.

Blows from a sledgehammer were falling on the town; houses were being scattered as if scraped by hooves, the agony of a cow bigger than the sky that refused to die and that someone kept on trying to club to death. Rubble flew up in the smoke like flocks of pigeons. When it cleared a little, they could see a church of some sort, its legs stiff in the air, its huge stomach bloated, dead.

Is that Alsace? said Marroi.

What is it? asked Olivier.

Whats that?

That town?

Verdun, said Doche.

The slaughterhouse, said Marroi.

Jean Giono, Monte Verdun (Going up to Verdun), a discarded chapter from the novel Le Grand Troupeau (To the Slaughterhouse), 1931, published in Refus dobissance (Insubordination), 1937

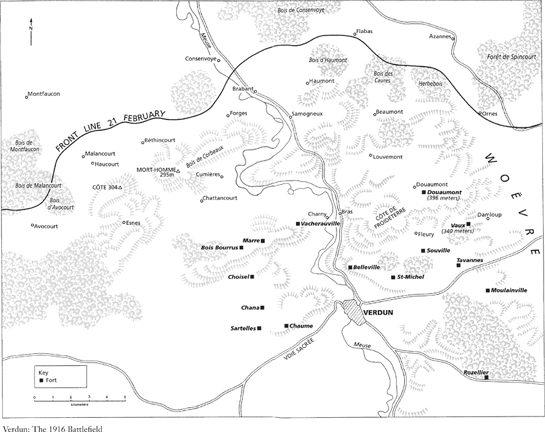

I t would almost seem that nature, as well as the destiny of nations, intended Verdun to be a place of battle. There is nothing remarkable about the city itself: like so many of the places where soldiers have passed the centuries fighting, it holds no special interest, let alone charm. Its terrible prominence has always come from its position by the river Meuse, dominating the only convenient crossing for some distance in either direction. This alone has guaranteed that it has stood on the route of invasion. That invasion would be contested here was guaranteed by the hills rising above the right (or east) bank of the river, sometimes called the Hauts de Verdun but more usually the Hauts de Meuse. Even before battle made it desolate, the countrysidesaid one historian and soldier who fought herewas already harsh and melancholy. Deep and often unexpected ravines mold the hills into a series of plateaus that seem to invite the wind and the rain during the bitter winters. The hills reach their highest point, a little over 400 meters, where they overlook the dreary plain of the Wovre.

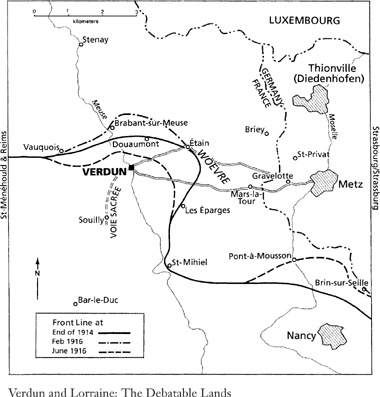

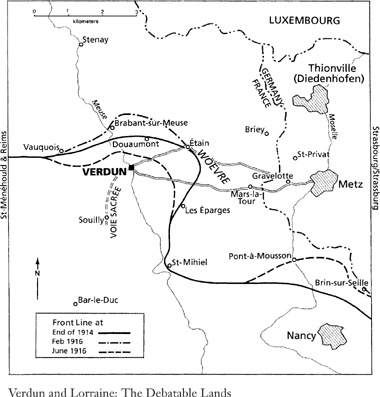

Beyond, further east, lie the Moselle and another cluster of hills, around Metz; beyond them, Strasbourg and the Rhine. It has always been debatable land. The quarrel reaches back at least to the treaty, bearing Verduns name, agreed between Charlemagnes grandsons in 843. It divided Charlemagnes Empire into a western kingdom, corresponding roughly to modern France, and an eastern kingdom, corresponding roughly to modern Germany, but also a short-lived middle kingdom. This kingdom might soon have vanished from the map but it bequeathed to history more than a name, Lotharingia, which time transmuted into Lorraine (known to the Germans as Lothringen). Lotharingia also left a sinister ghost. Its thin strip of land, running from Belgium, Holland and the North Sea to Provence and the Mediterranean, marked a fault line between the nations of western Europea territory of vulnerable small states, unstable boundaries and battlefields, from Agincourt and Blenheim to Waterloo and Sedan.

Nowhere was the land more debatable, the border less stable, than between the Meuse and the Rhine. Germanys annexation of Alsace and part of Lorraine after her victory in the Franco-Prussian War of 187071 moved the border from the Rhine to Metz, only 60 kilometers away from Verdun. So the French set about strengthening their natural bulwark with forts on either side of the river but clustered most thickly in the Hauts de Meuse. In the autumn of 1914 Verdun stood at the junction point, or hinge, between the two main arms of the German advance: the attack through Alsace and Lorraine in the south, largely a feint, and the real strike through Belgium and northern France which was brought up short on the Marne at the beginning of September. The German armies had managed to cross the Meuse near the little town of Brabant, only about 15 kilometers north of Verdun, and they dominated the river from Saint-Mihiel, about 35 kilometers south. But Verdun itself held, as it would again resist attacks from the flanks at Vauquois and Les parges in 1915.