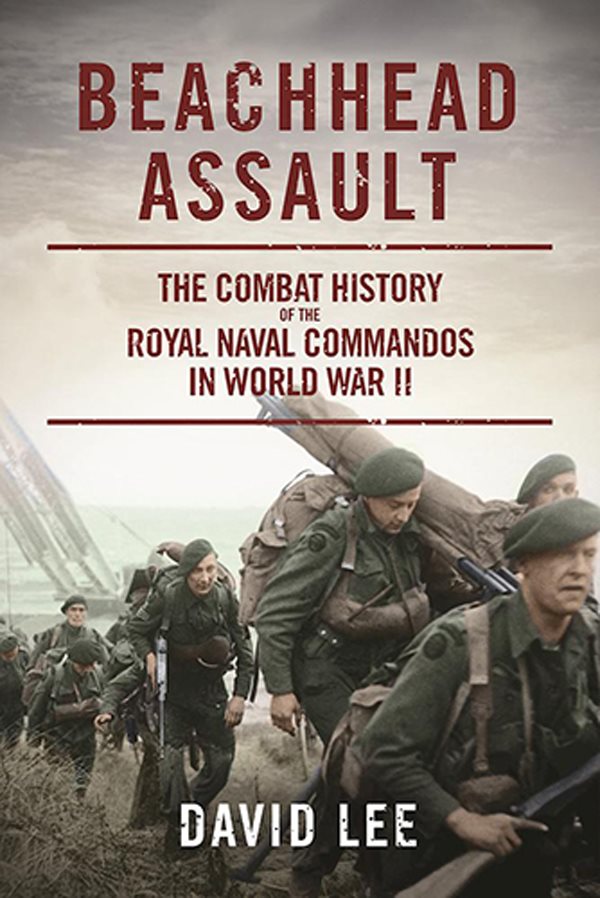

First published by Greenhill Books in 2004.

First Skyhorse Publishing edition 2017.

Copyright 2004 by David Lee

Foreword 2017 by Dennis Showalter

Preface 2004 by Ken Oakley

All rights to any and all materials in copyright owned by the publisher are strictly reserved by the publisher.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Rain Saukas

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-1775-6

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-1778-7

Printed in the United States of America

For the Commandos

Contents

Illustrations

Maps

Foreword

by Dennis Showalter

The most complex, difficult, and hazardous combined arms operation of World War II was a large-scale landing against a defended objective. The experiences of World War I hardly served as even a negative guide for this type of action. Gallipoli had been one fiasco after another. Smaller operations like the British landing at Tanga in 1914, even unopposed movements like the Allied occupation of Salonica the next year or Americas interventions in the Caribbean, tended to dissolve into compound confusion. The Germans had been more successful in their 1917 attack on the Baltic Islands, but that had required a disproportionate amount of the Second Empires navy and profited even more from the Russian garrisons endemic demoralization.

Amphibious operations, in short, were regarded after 1918 as things best left alone. Even the US Marine Corps planned its theoretical future operations in the Pacific on small scales. Then a new world war presented the same spectrum of problems in a far more challenging matrix. In particular, the German overrunning of Western Europe on 1940 left Britain in a quandary. Sooner or later, if the Axis were to be defeated, the war must be taken to them directly. And for Britain to play any significant part in that process would involve landing on beaches, staying there, and driving inlandall in substantial force.

Such an operation required a spectrum of specialized equipment unimagined in 1919. It required new doctrines, new concepts of command that challenged centuries-old decisions of responsibility between armies and fleets. And it required something elsesmall, unspectacular, and essential. The pinprick raids mounted against Nazi Europe in 1940-41 confirmed the need of O-rings: small units of specialists, maids of all work trained to expedite the landing of the assault force and its supporting elements, keep the landing craft on course, and get them unloaded and turned around promptlyand also able to defend themselves should enemy action make it necessary.

The Royal Naval Commandos were the answer. These landing parties supported the ground forces for extended periods of time and were always welcome because their sailors could turn their hands to anything that needed doing, and fight just as well as the soldiers. When the commandos were first organized it seemed natural for the Navy to contribute its own beach parties. These in turn were enlarged, reorganized, and trained as specialists in expediting landings. In the process they acquired a new title as well: the Royal Navy Commandos.

From the beginning they proved not merely their worth but their indispensability. They saw action in every theater of war, but their major contribution came on June 6, 1944. D-Day was an operation that could only be mounted oncenot least because it absorbed the last of Britains dwindling resources. Failure was not an option. The Royal Navy Commandos were in the first wave, took heavy casualtiesand established a level of order on the British beaches that far surpassed the corresponding American performance.

In the best traditions of the nineteenth century naval brigades, some of the commandos remained on the beaches for as long as six weeks. Yet they remained invisible, making no headlines, collecting few medals, disbanded without fanfare once the war ended. To a degree this relative anonymity reflected the Commandos being confused and conflated with other, similar special-mission forces like the Combined Operations Pilotage Parties and the Royal Marine Boom Patrol Detachment. But it also reflected the Royal Navys long-cultivated image as the service that emphasized deeds over words. And it reflected the fact that most of the commandos were hostilities only ratings, anxious above all to return home and resume or begin civilian lives.

In time, the veterans and their families sought to remember their service with advantage. The Combined Operations Command, to which the commandos belonged, has a flourishing web page. The Royal Naval Commando Association endured until 2003. And the organization produced more than a few books. Beachhead Assault is one of the best. Based primarily on extensive veterans memories, diaries, and notes, it conveys the spirit as well as the deeds of a unique organization and its unobtrusive contributions to Allied victory and British achievement.

Preface

by Ken Oakley

On behalf of my Royal Naval Commando Association friends, I welcome this book about us and our work on the beaches during the many landings of World War II.

We received many awards for our work but all were hidden under the designation Royal Navy because of the Wartime Secrets Act; it was never Royal Naval Beach Commandos or Royal Naval Commandos. My own unit, Fox Commando, was awarded five Distinguished Service Medals, two Mentioned in Dispatches, two Croix de Geurre, three Distinguished Service Crosses and one Bar to the DSC for D-Day. My own Mentioned in Dispatches was for Sicily.

I served two years at sea (19402) on the cruiser HMS Neptune and the battleship HMS Queen Elizabeth before being drafted into Combined Operations. After Lord Louis Mountbatten took command of Combined Operations an order was sent out for Royal Naval men to be trained to Commando standard for the beach landings. This training was carried out at HMS Armadillo , Ardentinny, and at Achnacarry and Inverary, as well as at many other places in Scotland.

My unit took part in the landings in North Africa, Sicily and Normandy. In 1945 I was promoted to Leading Seaman, and in the same year I was married and the best man was Sidney Compston DSM whom I helped to rescue on D-Day. In 1947 I finished my seven years service in the Royal Navy.

In 1983 I joined the Royal Naval Commando Association and was pleased to meet and swing the lamp again. I was invited to join the Committee and accepted the position of Chairman, in which capacity I was invited to the VE Day Reception and Dinner at the Guildhall. It was a wonderful occasion which I will never forget.

Now that the Association has disbanded I am very pleased the Commandos will continue to have a voice in this book. Thank you.

Authors Preface

World War II saw a new type of elite soldier. The Commandos. But the Commandos never belonged to just one branch of the Armed Forces during World War II.

Next page