THE BACKGROUND TO THE OPERATION

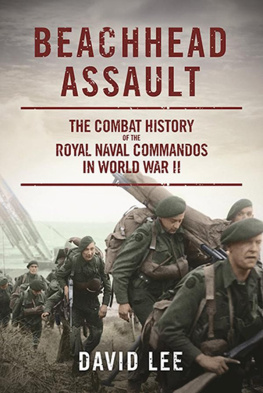

LtCol Augustus Charles Newman VC, known as Colonel Charles to his men. He commanded 2 Commando and was designated Military Force Commander for the raid. The majority of the commandos who took part in Operation Chariot came from 2 Commando. (Imperial War Museum, HU 16542)

On 24 May 1941 the battlecruiser HMS Hood and the battleship HMS Prince of Wales confronted the German battleship Bismarck and the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen in the north Atlantic. After just ten minutes of action the pride of the British fleet, the Hood, blew up and sank. The two German ships then concentrated their fire on the Prince of Wales, causing it some damage. The engagement was soon broken off and the British battleship withdrew, but not before Bismarck itself had been hit, causing her to lose fuel oil and take in sea water. Later that day she separated from the Prinz Eugen and set a course for the French port of St Nazaire. History will relate that she was intercepted on route by a superior British naval force and sunk.

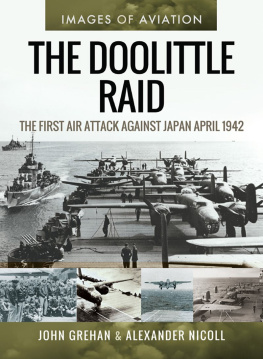

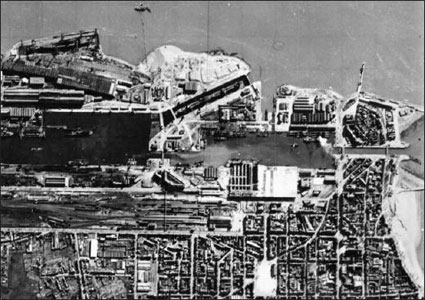

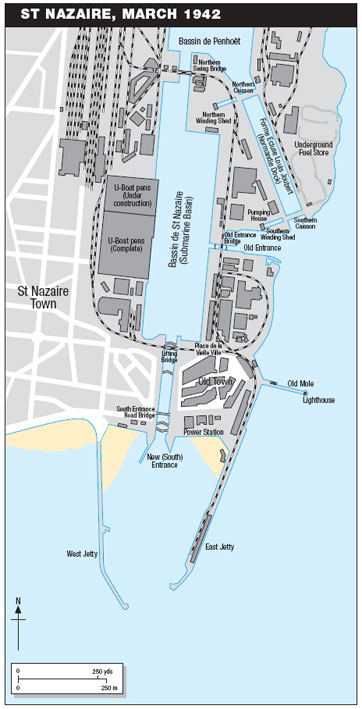

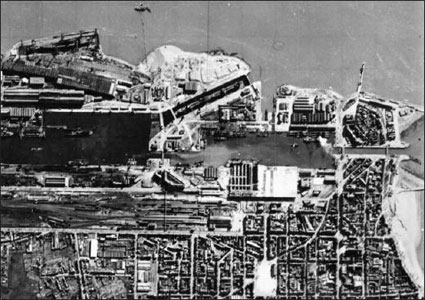

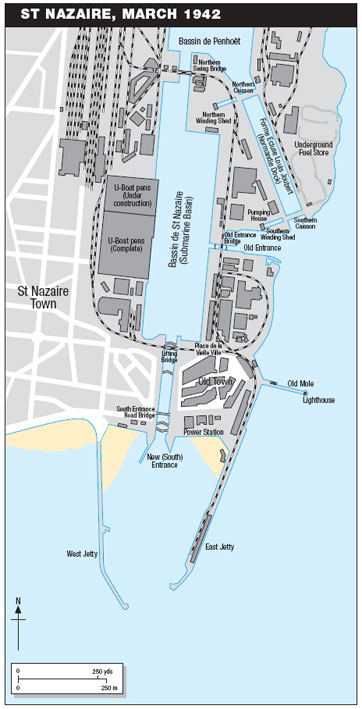

The town and port of St Nazaire lying on the western side of the River Loire, six miles from the sea. The Normandie Dock (Forme Ecluse Louis Joubert) is seen lying at an angle near the mid-top of the picture. At the top right, jutting out into the river, is the Old Mole. The section of water in the middle of the picture is the Submarine Basin, with the incomplete submarine pens below and the Southern Entrance to the docks on the right. (Imperial War Museum, C3465)

St Nazaire contained the only dry dock on the Atlantic coast capable of handling the great German warship. The massive Normandie Dock in the port was, at that time, the largest dry dock in the world. It was completed in 1932 to hold the great passenger liner Normandie and remained at the centre of the important shipbuilding and repair facility that thrived in the town prior to the war. When the Bismarck was damaged the dockyard at St Nazaire became the immediate and obvious destination for the battleship. It was fortunate for the British that she never arrived at the port, for once safely within the heavily fortified perimeter, the ship would have posed a sustained threat to Atlantic commerce and would have been a very difficult target to attack. Indeed this point was well illustrated a little later when the two great battle cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau remained holed up in Brest for several months, surviving a series of unsuccessful bombing raids by the RAF which caused them virtually no damage at all. In February 1942, they broke out of the port and dashed through the English Channel, defying the Royal Navy, the Royal Air Force and numerous coastal gun batteries to join up with other German capital ships in the relative safety of the Baltic ports.

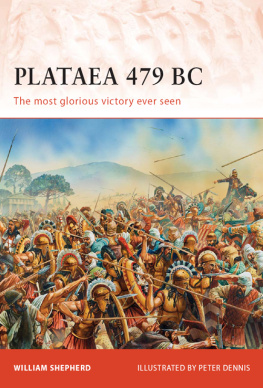

The German battleship Bismarck after she had been damaged by HMS Prince of Wales during the action in which HMS Hood was sunk. Bismarcks focsle is lying low in the water and she is making for the great dry dock at St Nazaire on the French Atlantic coast for repair. (Imperial War Museum, HU 400)

The end of the Bismarck did not free the British Admiralty from the spectre of a powerful German strike force breaking loose in the Atlantic, for the Bismarck had an even more powerful sister ship, the Tirpitz, nearing completion in Germany. In 1941 Britain was fighting alone and depended on its sea routes to supply the material it needed to feed its people and to prosecute the war against the Axis powers of Germany and Italy. The success of the German submarine campaign against its shipping often caused great hardship and shortages, but the German U-boats could be attacked, and often contained, by small destroyers and frigates. Battleships and heavy cruisers were another matter entirely. These great leviathans could only be countered by other capital ships or aircraft and the availability of these weapons in the vast wastes of the North Atlantic was limited.

The existence of this German battleship, the Tirpitz, was the prime reason for the raid. The mere threat of the ship breaking out into the north Atlantic was enough to keep several British battleships idle, waiting to react should such an event take place. (Imperial War Museum, HU2627)

In January 1942 the Tirpitz became operational and left the Baltic for the shelter of the Norwegian fjords. The threat that the battleship posed, and the realisation of what it could do to Britains vital supply lines, became almost an obsession with the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill. The mere existence of Tirpitz meant that four British capital ships had to be held in readiness at all times, waiting for her should she exit into the deep waters of the Atlantic. Added to this force were two battleships provided by the Americans, who had entered the war in December 1941. Churchill told his Chiefs of Staff that no other target was comparable to the destruction of the great German capital ship. He even went so far as to say that the whole strategy of the war turned on her mere existence. This message was not lost on the leaders of Britains war effort who were all too aware of the Tirpitzs awesome reputation. Both the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force were already devising methods of using their hard pressed resources against the German battleship.

Whilst one arm of the Admiralty was attempting to organise the elimination of the Tirpitz as she lay at anchor, other planners were tackling the question of what to do should she ever break out. The Admiralty knew that if the Tirpitz ventured into the great Atlantic Ocean, she would need a safe refuge to return to, especially if she was unlucky enough to sustain damage such as that which befell the Bismarck. The only dock which was large enough to be able to take her for repairs was that provided by the port of St Nazaire. Thus, if this facility was denied to them, it was unlikely the German Navy would risk the Tirpitz in the Atlantic. Any aggressive sorties she might make would have to be confined to those colder waters ploughed by the Arctic convoys. A means had to be found to render the dry dock unusable.

CHRONOLOGY

1932

April

- The largest dry dock in the world is completed in St Nazaire to hold the great Atlantic luxury liner Normandie.

1940

10 May

- Hitler begins his invasion of France and the Low Countries, sweeping all opposition aside.

4 June

- Bulk of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) is evacuated from Dunkirk.

17 June

- The liner Lancastria is sunk whilst evacuating the last troops of the BEF from St Nazaire. Over 4,500 people are missing, creating the greatest single loss of life in British maritime history.

21 June

- France surrenders and signs an armistice with Germany, agreeing to the Nazi occupation of half the country. The German Army moves to occupy the whole of the Atlantic coast of France.