CONTENTS

He picked up the Colt M1911A1 .45 pistol with a smile of recognition.

This was my personal weapon.

He turned it over, looked at its functional lines and felt its familiar weight.

Training and the harsh test of war had given him a confidence with weapons that was instantly recognisable to the group of soldiers gathered around him.

The pistol was part of a display of Second World War weapons used by British commandos. The speaker a veteran of No. 4 (Army) Commando was addressing officers and non-commsioned officers (NCOs) of the Infantry Trials and Development Unit (ITDU) Warminster before they embarked on a battlefield study of Operation Jubilee.

I was to be their guide, taking them to the beaches around Dieppe where, on 19 August 1942, men of the Canadian 2nd Infantry Division fought and died in Operation Jubilee, a brief and disastrous amphibious assault on the French port.

The only part of the operation that was a success was Operation Cauldron, the attack by No. 4 Commando on a flanking German coastal battery code-named Hess. It was a well-planned and superbly executed attack. At the time James Dunning, the speaker at Warminster, was the 22-year-old Troop Sergeant Major of C Troop, No. 4 Commando armed with a Colt 45.

The men of the ITDU hung on his words as he described the formation of commandos and their role in the Second World War. In 1940, commandos were a new and untried force made up of volunteers prepared to undertake hazardous but unspecified operations against the enemy.

It was a chance to hit back.

In 1940, many British soldiers of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) had escaped from France over the beaches of Dunkirk only months before they were proud men who felt that they had been driven off the continent of Europe in what had not been a fair fight. Now the enemy had turned the towns and cities of Britain into a battleground as Luftwaffe bombers pounded these vulnerable targets, and their families and friends were forced into the front line.

Many saw the air attacks as a precursor to a massive German amphibious assault on the British Isles and its occupation by an alien and cruel power.

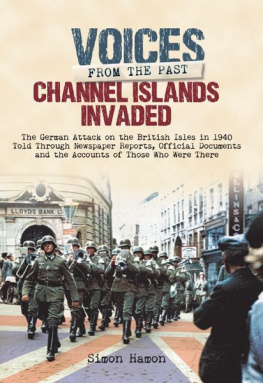

Across the Channel there was already a miniature version of what life under German occupation would be like. The Channel Islands, which had resisted the French for centuries, had been captured by the Germans without a fight in June 1940, and now the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, wanted to challenge these complacent occupiers of this small part of Britain.

Following the evacuation from Dunkirk, he demanded that the armed forces should take the war back to the enemy. One of the most dramatic developments in this fightback would be the formation of commandos volunteers from the army and later the Royal Marines who would raid the coastline of German-occupied Europe.

It was obvious, therefore, that Churchill would insist that the Channel Islands were on the commandos target list.

In all there would be seven raids on the Channel Islands. The first, Operation Ambassador on 15 July 1940, was so ineffective, with men and equipment being abandoned for absolutely no tactical gains, that there was talk among senior army officers that the fledgling commandos should be disbanded.

In contrast, Operation Dryad on 3 September 1942 was a well-planned and very effective attack that captured the entire crew of seven men on the Casquet lighthouse, along with their code books and other documents.

Though in itself a small-scale action, Basalt in October 1942 would have repercussions that no one could have anticipated. Because there were reports that German prisoners had been tied up and shot, an enraged Hitler issued the secret Commando Order; this required that any captured Special Forces were to be executed a fate that befell members of the SAS and commandos later in the war.

There are some less well-known plans for operations against the Channel Islands that were proposed in 1943 by Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, then heading combined operations. Some were large-scale raids, even landings with armour and paratroops supported by naval gunfire and bombers. Had the operation been launched, the casualties would have been worse than the losses suffered by the Canadians at Dieppe in August 1942.

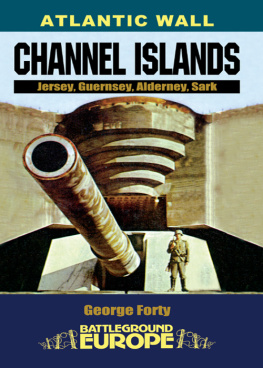

During the war the Channel Islands would become an obsession for three powerful men: Churchill, who was angered that British territory was now under enemy control; Mountbatten, who proposed the potentially costly and impractical operations; and Hitler, who was determined that the Channel Islands would remain German forever and was the driving force behind a massive programme of fortification.

Allied commando raids were launched against the islands between 1940 and 1943. However, the most unusual raid was that launched by the Germans from Jersey in March 1945, which saw a mixed force of soldiers, Luftwaffe gun crews and sailors land at the Allied-controlled French port of Granville. Their main mission was to capture British colliers and bring them and their valuable cargo back to the Channel Islands to ensure that the power stations were kept fuelled. They captured one collier and destroyed port installations, as well as taking prisoners. These German servicemen on the raid were to be some of the last men to be awarded the Knights Cross during the Second World War.

Following the Granville raid, the enraged Americans proposed that Allied bomber forces should pound the islands harbours to deter any further seaborne attacks but fortunately for the civilian population the war ended a couple of weeks later and the garrison on this last outpost of the Third Reich went quietly into captivity.

Visit the Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery at Bayeux in Normandy and you will see the neat rows of distinctive British and Commonwealth headstones, with the name, age, rank, service number and cap badge of the young man or woman buried in the ground below. At the foot of the headstone is a short personal tribute from the wife or more often the parents who had been listed in the soldiers documents as next of kin.

It is over seventy years since D-Day and the fighting in Normandy, but these tributes still resonate with the surge of pain, resignation and tearful pride felt when the reluctant telegraph boy delivered the buff envelope, and parents or wives picked out the typed phrases such as killed in action or missing presumed dead.

Some 4,648 servicemen and women are buried at Bayeux, including 466 German soldiers. In a block on the right is the grave of a 38-year-old lieutenant in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (RNVR) named Fredrick Lightoller. He was killed in action on the night of 9 March 1945 at the small northern French port of Granville. He was one of six British sailors, both Merchant and Royal Navy, and seventeen men of the US Navy and Army to die in a German amphibious raid launched from the Channel Island of Jersey.

Across the road from the cemetery is the pillared Memorial for the Missing. On it are listed the names, ranks and regiments of 1,805 servicemen and women who were killed, but whose bodies were never recovered. At the top of the memorial is the proud motto: NOS A GUILIEMO VICTI VICTORIS PATRIAM LIBERAVIMUS (We, once conquered by William, have now set free the Conquerors land).

At the far right-hand end of the memorial, high on one of the limestone panels, are the names of men from the Special Air Service (SAS), killed in France in the bloody fighting after D-Day. Some may have been captured and murdered by the Germans and their bodies dumped into unmarked graves: they were the victims of Hitlers notorious Commando Order an order prompted by a commando raid on the German-held Channel Islands. This is the story of that raid and its tragic consequences, and of others against these islands, the first of which went so badly wrong that it nearly spelled the end of the fledgling commando idea.

Next page