Abdiel Oate, professor of Latin American studies at San Francisco State University

William H. Beezley, series editor

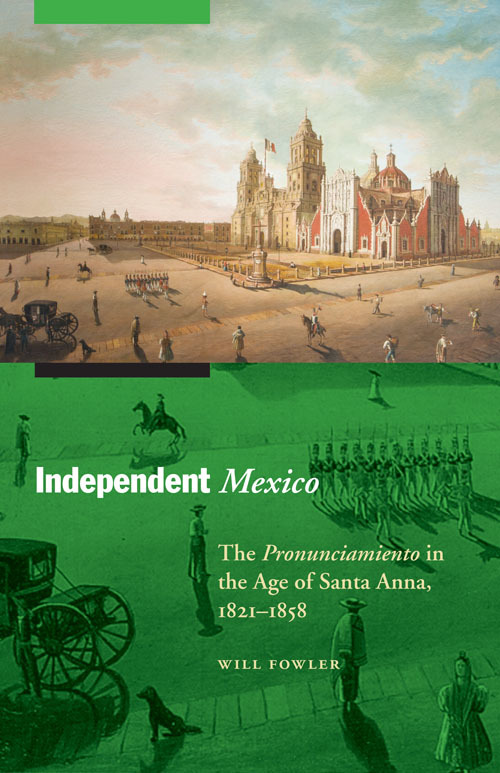

Independent Mexico

The Pronunciamiento in the Age of Santa Anna, 18211858

Will Fowler

University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln & London

2016 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska

Cover image: Plaza Mayor de la Ciudad de Mxico de 1850. Pedro Gualdi, Museo Nacional de Historia INAH . The reproduction is authorized courtesy of the Instituto Nacional de Antropologa e Historia.

Author photo courtesy of Peter Adamson

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fowler, Will, 1966 author.

Independent Mexico: the pronunciamiento in the age of Santa Anna, 18211858 / Will Fowler.

pages cm.(The Mexican experience)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8032-2539-8 (pbk.: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8032-8467-8 (epub)

ISBN 978-0-8032-8468-5 (mobi)

ISBN 978-0-8032-8469-2 (pdf)

1. MexicoPolitics and government18211861. 2. Government, Resistance toMexicoHistory19th century. 3. Coups dtatMexicoHistory19th century. 4. RevolutionsMexicoHistory19th century. 5. MexicoHistory18211861. I. Title.

F 1232. F 69 2016

972'.04dc23

2015031797

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

For Caroline

... the absurd events of a land incapable of tranquility, enamored of convulsion.

Carlos Fuentes, The Death of Artemio Cruz (translated by Sam Hileman; Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1979 [1962]), 37

When a law is unfair, the correct thing to do is to disobey.

Banner displayed in the Zcalo during a demonstration in Mexico City on 7 July 2012, El Pas, 8 July 2012

When the unjust becomes the law, rebellion becomes a duty.

Banner displayed outside Mexican Senate, La Jornada, 2 October 2012

Contents

This book is about pronunciamientos and a phenomenon I have chosen to term mimetic insurrectionism. It is about an insurrectionary practice that became widespread in Independent Mexico whereby garrisons, initially, but eventually also town councils, state legislatures, and a whole array of political actors, groups, and communities took to petitioning the government aggressively at both a national and a local level to address their grievances during what amounted to a period of considerable constitutional uncertainty. Albeit often translated as a revolt or a coup dtat, the pronunciamiento was a complex form of insurrectionary action that relied, in the first instance, on the proclamation and circulation of a plan that listed the pronunciados demands and, thereafter, on its endorsement by significant enough a number of copycat pronunciamientos de adhesin or allegiance to force the authorities, be they national or regional, to the negotiating table.

It is a study that has its origins in a paper I gave at the then Institute of Latin American Studies in London in May 1997 on civil conflict in Independent Mexico and that builds on the subsequent research and publications that were developed ten years later as part of the University of St. Andrews Pronunciamiento in Independent Mexico project, which was funded by an incredibly generous grant from the UK-based Arts and Humanities Research Council ( AHRC ). It was while preparing an overview of civil conflict in Independent Mexico back in 1997 for the Nineteenth-Century History Workshop that Eduardo Posada Carb organized On the Origins of Civil Wars in Nineteenth-Century Latin America that I was first struck by the fact that the literally hundreds of pronunciamientos recorded in Mexico following its achievement of independence from Spain in 1821 were not strictly speaking revolts and that their threats of violence were seldom actually carried out. Once the Pronunciamientos Project got under way in 2007, it became more than evident that there was much more to the pronunciamiento phenomenon than I had ever anticipated.

In the first of the four volumes to arise from our AHRC -funded project, Forceful Negotiations: The Origins of the Pronunciamiento in Nineteenth-Century Mexico (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2010), the contributors established that the pronunciamiento became a common phenomenon in the Hispanic world in the nineteenth century. We argued that it was a practice (part petition, part rebellion) that sought to effect political change through intimidation and that was adopted to negotiate forcefully. We showed, moreover, that the pronunciamiento developed alongside Mexicos constitutions and formal political institutions and was resorted to, time and again, to remove unpopular politicians from positions of power, put a stop to controversial policies, call for a change in the political system, and promote the cause of a charismatic leader and/or the interests of a given region, corporate body, or community. We concluded that the pronunciamiento became the way of doing politics.

In the second edited volume of our pronunciamiento tetralogy, Malcontents, Rebels, and Pronunciados: The Politics of Insurrection in Nineteenth-Century Mexico (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012), we explained why this was the case. The process whereby the pronunciamiento went from originally being a military-led practice to one that was endorsed and employed by civilians, priests, indigenous communities, and politicians from all parties was traced through the study of a rich variety of pronunciamientos stretching from Tlaxcalan pueblo political activities in the late colonial period to a socialist levantamiento (uprising) with anarchist overtones in Chalco in 1868, with the stress being on individual and collective motivation.

In the third edited volume in the series, Celebrating Insurrection: The Commemoration and Representation of the Nineteenth-Century Mexican Pronunciamiento (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012), we focused on how Mexicans tried to come to terms with this practice, how they attempted to legitimize it by celebrating it and including it in their repertoire of civic fiestas, and how these fiestas came to reflect the ambivalence people felt toward the pronunciamiento. We sought to explain how pronunciamientos were celebrated, remembered, commemorated, and represented. In so doing, what emerged was a striking interpretation of a phenomenon that was characterized by its duality and ambivalence, one that was experienced as a necessary evil, celebrated yet criticized, reluctantly justified, and the heroes of which were both damned and venerated.

In this current fourth and final volume I have set out to provide a comprehensive overview of the pronunciamiento practice in Independent Mexico, with the emphasis being on national pronunciamientos. It is a book concerned with the dynamics of the pronunciamiento and, in turn, with how a given form of insurrectionary action can spread and become adopted by growing numbers of groups and individuals. It is also a study that highlights the extent to which this given model of political contestation evolved between 1821 and 1858, in terms of who pronounced, and why and how they did so, while paying attention to the shift that was also experienced in the kind of demands pronunciamientos set out to address. Therefore I provide in chapter 1 a critical review of the relevant literature while offering a detailed analysis of the nature of the pronunciamiento as a political-insurrectionary practice. I go on to define and explore in the following chapter the dynamics of mimetic insurrectionism. Here I provide an interpretation of how the pronunciamiento, as a phenomenon, became such an emulation-worthy practice on the back of the successful pronunciamientos of Cabezas de San Juan in Spain, on 1 January 1820, and of Iguala, on 24 February 1821, but also because of the context of severe constitutional crisis in which it originated. Chapter 3 then addresses how the pronunciamiento started to spread in the first decade following independence, and I argue that a key factor in its proliferation was the manner in which regional elites used it to renegotiate their political power with the center. As becomes evident in chapter 4, by the 1830s it was not just high-ranking officers in collusion with the