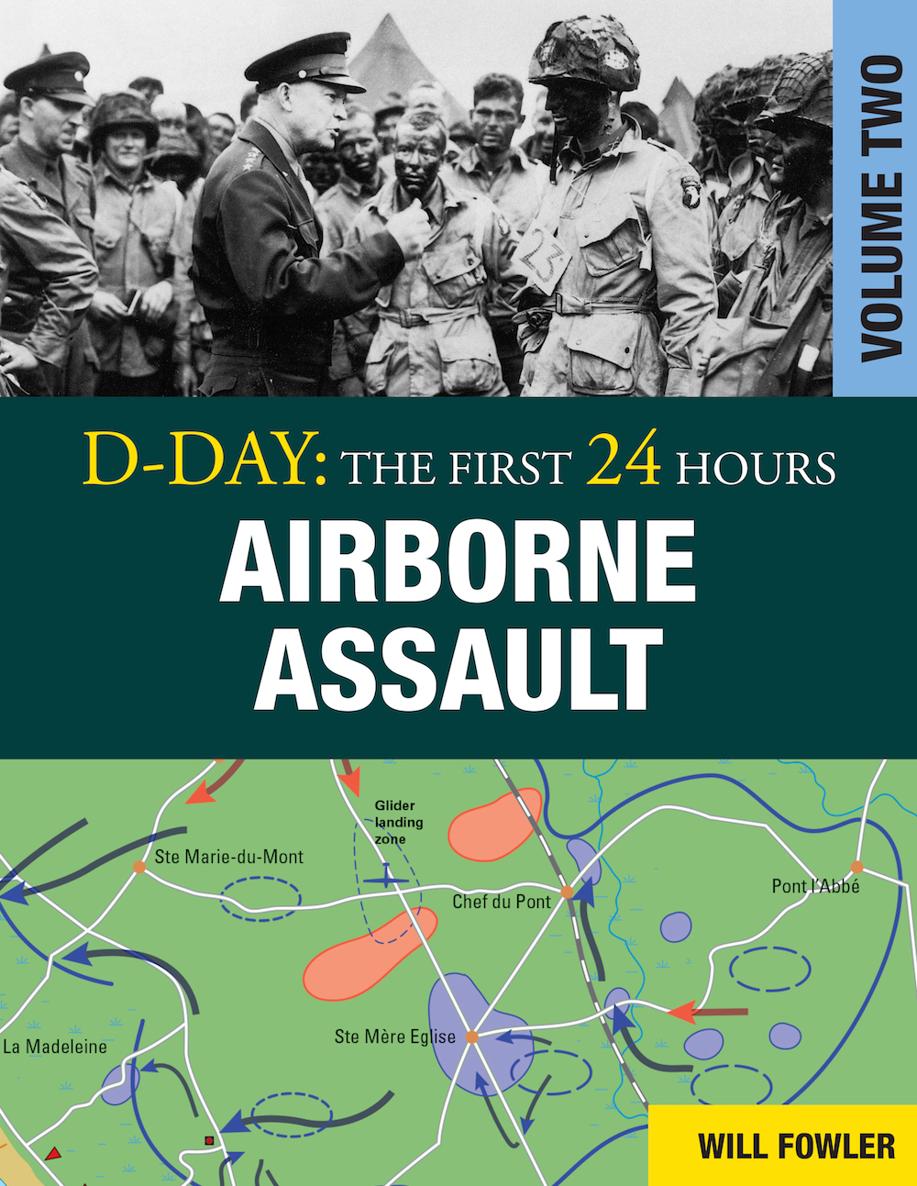

D-DAY:

Airborne Assault

D-Day: The First 24 Hours Volume 2

WILL FOWLER

This digital edition first published in 2014

Published by

Amber Books Ltd

7477 White Lion Street

London N1 9PF

United Kingdom

Website: www.amberbooks.co.uk

Appstore: itunes.com/apps/amberbooksltd

Facebook: www.facebook.com/amberbooks

Twitter: @amberbooks

Copyright 2014 Amber Books Ltd

ISBN: 978 1 909160 51 4

PICTURE CREDITS

Amber Books; TRH Pictures; US National Archives; John Csaszar; Photos12.com; Popperfoto; Sddeutscher Verlag; Topham Picturepoint; Peter Harper; Patrick Mulrey

All rights reserved. With the exception of quoting brief passages for the purpose of review no part of this publication may be reproduced without prior written permission from the publisher. The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. All recommendations are made without any guarantee on the part of the author or publisher, who also disclaim any liability incurred in connection with the use of this data or specific details.

www.amberbooks.co.uk

CHAPTER ONE

SPECIAL

OPERATIONS

Though the bulk of Operation Overlord would be a huge amphibious attack supported by large scale airborne landings, there were some targets like coastal batteries and bridges that would require attacks by specialist troops. Though the gun sites could also be bombarded by warships, these direct assaults were a way of guaranteeing that enemy guns would not disrupt the landings. Each attack would become a separate epic action within the larger-scale attacks in Normandy.

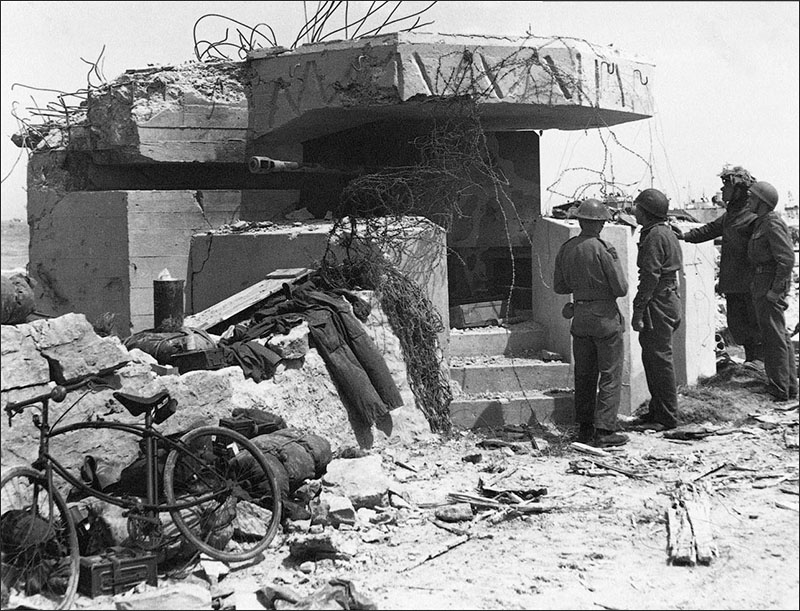

ALTHOUGH 73 IDENTIFIED coastal gun positions around Normandy had been pounded from the air, Allied planners could not be certain that the guns inside the massive concrete emplacements had been destroyed. If they were even still partially effective they could cause casualties and slow down and disrupt the Allied landings by shelling ships and landing craft.

Two positions were identified as critical to the landings. At the Pointe du Hoc, which a typing error in Allied plans labelled as the Pointe du Hoe, the Germans had concrete casemates which were believed to house 155mm (6.1in) guns with a range of 23km (15.5 miles). These guns could engage shipping running in to Utah beach as well as some around Omaha.

At the eastern edge of the beaches, on Sword beach, the Germans had constructed another battery position of four two-metre (6.5ft) thick casemates on high ground about 2.5km (1 mile) inland, at Merville. The observation post (OP) for the battery was at the edge of Sallenelles bay and was linked to the guns by a buried telephone cable. The battery was believed to house 150mm (5.9in) guns which, like those at the Pointe du Hoc, would be lethal to Allied shipping. At Merville, these guns were feared to have a range of over 12km (7 miles).

A flotilla of LCAs carrying US Rangers moves out from harbour into the Channel. Landing craft crews worked hard to learn how to run into the beach on a shelving shore, off load their cargo of men or vehicles and then, with engines full astern, pull back off the beach.

Allied planners also identified the Caen Canal and river Orne, running from Caen to the sea at Ouistreham, as a key feature. If the bridges across these wide water obstacles were demolished by the Germans, it would prevent the Allies breaking out eastwards and would help the Germans contain the beach head. Worse still, if the Germans held the bridges they could cross them to attack the Sword beaches near Ouistreham.

The only way in which the Pointe du Hoc could be neutralized with complete certainty was by an assault from the sea, but at this point, the cliffs were 30m (130ft) high. The men tasked with the mission of destroying the battery, the US 2nd Ranger Battalion, looked at the problem and came up with some novel solutions. At the foot of the cliffs was a narrow rocky beach. DUKWs fitted with 30m (100ft) firemens ladders, on loan from the London Fire Brigade, would land and deploy the troops. In addition, small assault ladders and rocket propelled grapnels and ropes would be used. The Rangers practised cliff assaults on the chalk cliffs on the Isle of Wight, and Swanage in Dorset. Their plan could work, as long as the German garrison had been stunned by the air and sea bombardment that would include broadsides from the battleship USS Texas.

FORECASTING D-DAY

The three key Allied weather forecasting teams were the British Central Forecasting Office at Dunstable on the Bedfordshire Downs, the US Army Air Force facility at Widewing near Teddington in the Thames Valley and the Admiralty in London. The USAAF at Widewing favoured launching Operation Overlord on 5 and 6 June because they were convinced that the Atlantic low front L5, that had brought bad weather, would be followed by L6 but this would north along the coast of Greenland, not towards Norway. Dunstable and the Admiralty demurred, convinced it would go east rather than north. It was left to James Stagg to examine the data and give his advice.

At the bridges over the Caen Canal and river Orne near Benouville there would be no air attacks or naval gunfire support. The men of the D Company, the 2nd Battalion Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry under Major John Howard would land in gliders almost directly on the bridges and use the shock of their midnight airborne assault to take the positions. However, if the Germans were alert to the danger, the British soldiers would die before they were out their seats in the glider surprise was critical.

ACTION AT MERVILLE

At the Merville battery, 9th Battalion the Parachute Regiment under Colonel Terence Otway would parachute into a Dropping Zone (DZ) at Varville 3km (2 miles) south-east of the position. The men would be faced with formidable defences that included minefields, an anti-tank ditch, thick barbed wire, eight machine guns and a 2cm (0.78in) anti-aircraft gun.

Like parts in a complex jigsaw, each of these three dawn assaults had to work if the larger pieces of the D-Day operation were to fit together. All of these plans were daring and the men very well trained, but like all special operations, they needed a large element of luck.

By D-Day, the Special Air Service (SAS) that had begun as a small special forces unit in North Africa had expanded to a full brigade within the British 1st Airborne Corps under command of Brigadier Roderick McLeod.