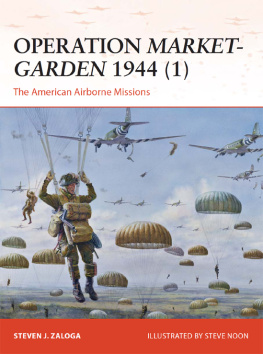

Battle Orders 25

US Airborne Divisions in the ETO 194445

Steven J Zaloga

Consultant Editor Dr Duncan Anderson Series editors Marcus Cowper and Nikolai Bogdanovic

Contents

Introduction

By the end of World War II, the US Army deployed the largest airborne force in the world, created in barely three years. Airborne operations were a revolutionary tactic that transcended the limits of traditional linear land warfare by conducting combat missions deep in the enemy rear through the use of airlift. During the final year of the war, the US Army conducted four airborne operations in the ETO. The airborne drops behind Utah Beach on D-Day were a tactical disappointment due to the wide dispersion of the airborne units after a confused night drop. In spite of this the mission was an operational success since it managed to disrupt the German defenses even if not in the fashion intended. Operation Dragoon in southern France on August 15, 1944, was the smallest of these operations and the least consequential since German resistance in the area was so weak. The boldest of the missions, Operation Market in September 1944, was part of a larger British scheme to seize a bridgehead over the Rhine at Arnhem. Although the overall mission failed, the two US airborne divisions taking part fulfilled their tactical objectives in a clear demonstration of the potential of airborne operations. The final airborne mission of the war, Operation Varsity in March 1945, was the best executed of the wartime airborne missions and spearheaded the British advance over the Rhine. Ultimately, the airborne divisions never lived up to their revolutionary promise. Airborne operations proved to be extremely complex to conduct and were too few in number to substantially affect the course of the campaigns in Northwest Europe. Yet the combat performance of the US airborne divisions was so outstanding that they have become a fixture in the US Army ever since.

Where is the Prince who can afford so to cover his country with troops for its defense, as that ten thousand men descending from the clouds, might not, in many places, do an infinite deal of mischief before a force could be brought together to repel them? So wrote one of Americas founding fathers, Benjamin Franklin in 1784, in a remarkably futuristic vision of warfare by balloon. In France in 1918, another visionary, Gen. Billy Mitchell, convinced Gen. Pershing to begin plans to drop an entire division of troops from bombers to take the fortress city of Metz from the air. The war ended before the plans could take shape. But curiously enough, the officer assigned the task of studying this project was Lewis Brereton, who would lead the US airborne force a quarter century later.

A dramatic scene from Landing Zone W on September 23, 1944, during Operation Market with CG-4A gliders of recently landed elements of the 101st Airborne Division in the foreground while in the background, the C-47 transports of the 315th Troop Carrier Group drop elements of the 1st Polish Parachute Brigade on Drop Zone O near Overasselt. (NARA)

When the idea of airborne troops was revived some 20 years later, the initial debate focused on who would actually train and command the force. The US Armys Chief of Infantry proposed the creation of a small air infantry force in March 1939 as the Marines of the Air Corps, or air grenadiers. The engineers argued that they should be placed under their control since their primary mission initially was seen as rear area demolition and sabotage. The War Departments G-3 section wanted them placed under their control as a strategic reserve of the general headquarters. The Army Air Force (AAF) wanted them under their control since their aircraft would be an integral part in the operations.

The startling success of German paratroopers at Eben Emael in Belgium in May 1940 made clear the potential of airborne forces and helped ensure the establishment of a counterpart organization in the US Army. In August 1940, the US Army General Staff finally decided to leave the new air infantry forces under the Chief of Infantry. A test platoon was formed at Fort Benning in June 1940, expanded to a battalion in September 1940. Later German operations, such as the airborne assault on Crete in May 1941, suggested that airborne forces could conduct missions much more substantial than mere airborne raids. The US Army quickly absorbed these lessons and the infant airborne force expanded rapidly following the US entry into the war in December 1941.

In March 1942, the Provisional Parachute Group at Ft. Benning became a formal part of the Army Ground Forces (AGF) as the new Airborne Command. Col. William C. Lee, who had been instrumental in the formation of the first US airborne units, headed this organization. By the summer of 1942, the Airborne Command had four principal units: three parachute infantry regiments (501st, 502nd and 503rd) and one airborne (glider) infantry regiment (the 88th). Equally important, in April 1942, the AAF formed the Air Transport Command responsible for the delivery of parachute troops, airborne infantry and glider units. At the time, three methods of airborne delivery were considered viable: parachute, glider and airborne landing. The presumption was that paratroopers would be used in any operation as the spearhead to seize a landing zone for gliders or an enemy airstrip for air-landing troops. The idea of air-landing infantry troops behind enemy lines at a captured airfield was based on the German use of this tactic on Crete in 1941, and the idea of glider landings was inspired both by Eben Emael and Crete.

The US airborne did not have a centralized command structure comparable to the German XI Fliegerkorps, which combined both the air transport formations and air-landing troops under a single tactical organization. This was made simpler by the fact that both elements were part of the Luftwaffe, while in the American case the two elements were divided between the AAF and AGF. Although various schemes were put forward to better coordinate these two commands, the substantial difficulties of raising and training the new formations, as well as inter-service rivalries, diverted attention from this issue. By the time that US airborne divisions were ready for commitment in the ETO, the broader issue of the coordination of US troop carrier units and their British counterparts, as well as coordination of US and British airborne operations, had become a much more vital issue.

The original US airborne force was based around regiments, not divisions, on the assumption that this would provide greater flexibility in planning and executing missions. However, the Germans had evidently used divisions on Crete and, by early 1942, the US Army was thinking along the same lines. At first, the AGF headquarters simply wanted to assign the airborne mission to normal infantry divisions that would receive additional training. However, airborne advocates strongly objected to this idea on the grounds that the infantry division organization was ill suited to air-landing operations and that the personnel would require too much specialized parachute training. By the summer of 1942, the consensus had reverted back to the idea of dedicated airborne divisions and Lee was dispatched to Great Britain to examine the British organization. Lee recommended the British mix of two parachute and one glider regiments per division, but the head of the AGF, Gen. Lesley McNair, preferred a mix of two glider and one parachute regiments. The argument over the balance of forces within the airborne was based partly on tactics and partly on economy. Parachute troops were seen as elite troops requiring more stringent recruitment practices and a much higher level of training. The regular infantry was wary of letting these units expand too much as there was the feeling that this would drain infantry units of highly motivated young troops who would otherwise serve as small unit tactical leaders in the regular infantry divisions. In contrast, glider infantry was not expected to require a high level of specialized individual training, and gliders were envisioned as cheap and reusable. From this perspective, the parachute regiment would serve as the spearhead to land and secure the landing zone, and would be followed by the glider regiments and perhaps some air-landed units as well. As a result, the first airborne divisions formed in August 1942, the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions, both had a mix of one parachute and two glider regiments. As we shall see, this issue would remain contentious through 194344.