Contents

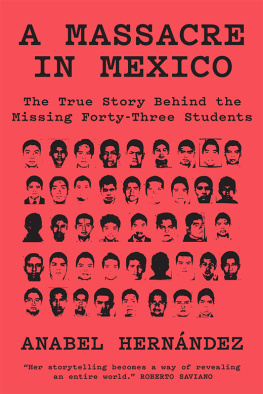

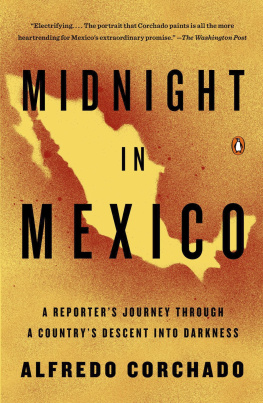

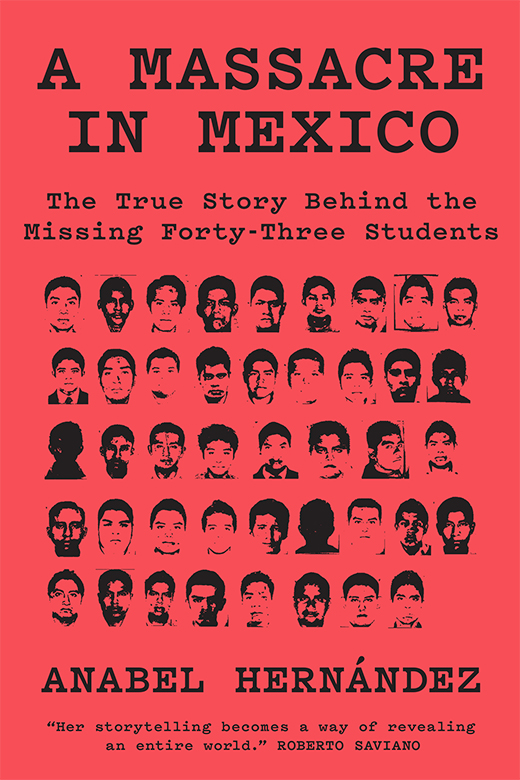

A Massacre in Mexico

A Massacre in Mexico

The True Story Behind

the Missing Forty-Three Students

Anabel Hernndez

Translated with an Introduction by John Washington

First published in English by Verso 2018

First published as La verdadera noche de Iguala. La

historia que el gobierno quiso ocultar 2017

Vintage Espanol 2017

Translation John Washington 2018

Introduction John Washington 2018

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-148-5

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-536-0 (EXPORT)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-151-5 (US EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-150-8 (UK EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the

Library of Congress. The LCNN is 2018016253

Typeset in Fournier MT by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed in the US by Maple Press

To all the victims of that interminable night: those who were disappeared, the survivors, the tortured, and the witnesses who had the courage to speak out.

To Roberto Scarpinato, whose capacity to fall in love with the destiny of others is a source of inspiration and hope.

They sought to bury them, not knowing that they were seeds

Anon.

Contents

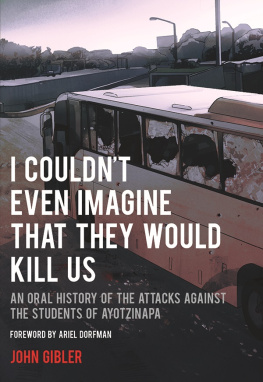

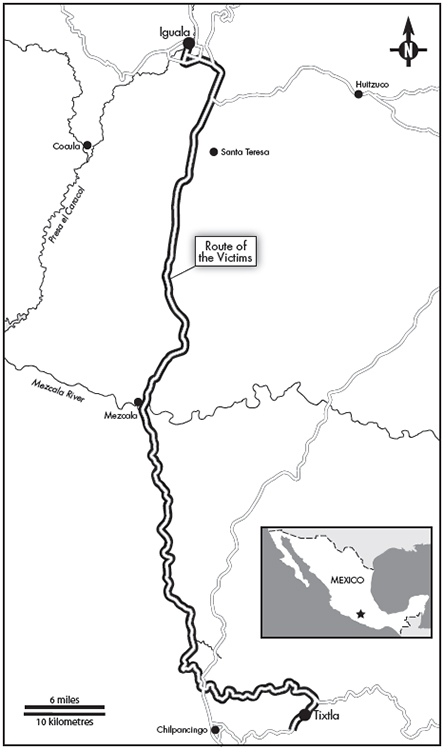

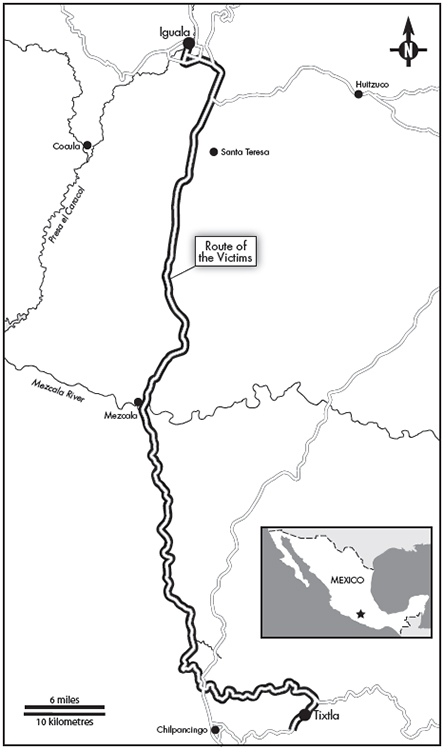

W ith no clear end, and no obvious beginning, this is a story that bleeds beyond linear timelines or basic geography. In the fall of 2014, a group of students from the Ayotzinapa teacher training school, mostly in their early twenties, commandeered passenger buses in the small city of Iguala, Guerrero. They took the busesan established, if, to some locals, annoying practiceto travel to Mexico City to commemorate the 1968 Tlatelolco Massacre, in which Mexican soldiers and police gunned down hundreds of innocent protesters. On that fall night in 2014, following a standoff earlier in the day, local, state, and federal security forces hunted down the unarmed students, shot and killed six people, injured dozens, and disappeared forty-three, all under the watchful and directive eye of the Army. After the disappearanceas news of the slaughter began to break across the worldthe government tampered with evidence, fabricated stories, lied to the international press, and brutally tortured the innocent men and women on whom it tried to pin the attacks. Tens of thousands of Mexicans took to the streets, chanting Fue el estado!

They were right, it was the state, and the demonstrations pushed the administration to the brink of collapse. Four years later, after weathering the storm with obfuscation, hollow promises, and a distracting onslaught of other scandals, the government remains in contempt of truth and in contempt of life. This is the endlessness of the story, the unhealing wound: no clarity, no justice. And every time or place you think youve found the beginning of the threadtracing the story back days, weeks, or decadesyou come across another tangle. Anabel Hernndez doesnt unsnarl all these shambles; rather, she presents the facts and history such that we glimpse an institution of cruelty and injustice that reaches far beyond that single night.

The massacre and disappearance of the students was different from other state-enacted slaughters of civilians only in degree, not in kind. Just months before the students were hunted down, twenty-two people were summarily executed by soldiers in Tlatlaya, in the state of Mexico. Their deaths stood out from the over 200,000 people killed in the decade of the drug war, as, despite government claims they had died in a standoff, the Army lined the victims up against a wall and shot them point-blank. They then tortured the sole surviving witness. Later, information was leaked that the soldiers hadnt merely been acting in wrath, they had been following orders.

Follow the thread, prod at another tangleblood feeds into Guerreros fertile soil. 2011: two Ayotzinapa students killed by police during a protest. 1995: the Aguas Blancas massacre, at least seventeen farmers slaughtered as they protested, among other things, for their right to clean water and against the disappearance of one of their leaders. These sorts of cold-blooded killings became common practice during the Dirty War, during which, from the late sixties to the eighties, the government killed and disappeared thousands, most notoriously in the 1968 Tlatelolco Massacrethe crime that the students were planning to commemorate in Mexico City. The violence seems to feed off itself, but thats not how violence works. Theres always someonein this case, el estadoholding, aiming, and firing the gun.

The students killed and disappeared that night were normalistas, studying at the Ral Isidro Burgos Normal Rural School in the small community of Ayotzinapa, in Guerrero state. The system of Normal Rural schools, based on pedagogy developed in seventeenth-century France, was initiated after the Mexican Revolution to train teachers in remote and mostly indigenous areas that the government had long neglectedand continues to neglect. Situated in areas of extreme poverty, with little to no infrastructure and high infant mortality rates, the Normal schoolsoffering free tuition and boardstand out as enclaves of opportunity and empowerment. The Normal schools afford alternatives to the local youth, those who want to remain in their communities.

The other options, which are few, include succumbing to the centripetal maw of Mexico City, signing up as pawns in the drug trade, or crossing the Arizona desert into el otro lado, where they would become prey for another violent paramilitary organizationthe US Border Patrol. For decades, Mexicos normal schools, though underfunded, politically undermined, and occasionally shuttered by the state, have been struggling to continue offering self-empowerment, indigenous pride, and the basic staples of education and community ethics to populations often relegated to cultural and economic attrition. It wasnt only those students who were attacked that nighttheir way of thinking, being, and even speaking have been tyrannized by the state for decades.

In the late sixties, Lucio Cabaas, the most famous alumnus of the Ayotzinapa Normal School, after witnessing and suffering multiple assaults from the police and the military, joined a nascent guerrilla group and ended up forming the Party of the Poor. As Omar Garca, a third-year student at the school and survivor of the 2014 attacks, explained, Cabaas and the others didnt think it was enough, because teachers shouldnt only care about what goes on in class. A teacher needed to see what the whole community was struggling with, get involved in the issuesnot ignore the kid who comes to school with rags for pants, underfed, belly bloated from hunger. We need to get involved in the issues, thats the essence of the rural normal schools.