CHANNEL ISLANDS INVADED

This edition published in 2015 by Frontline Books,

an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street, Barnsley, S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS

Copyright Simon Hamon, 2015

The right of Simon Hamon to be identified as the author of this work has been

asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-47385-159-7

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-47385-160-3

PRC ISBN: 978-1-47385-161-0

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or

introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means

(electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior

written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act

in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil

claims for damages.

CIP data records for this title are available from the British Library

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Typeset in 10.5/12.5 Palatino

For more information on our books, please email: ,

write to us at the above address, or visit:

www.frontline-books.com

Contents

Acknowledgements

The following individuals have been of tremendous help to me whilst compiling this book, and without their help it could never have been completed. Although the list is not exhaustive, those who have been of particular help are: John Goodwin, for his patience in having to listen to my progress, in offering advice, guidance and knowledge and in sharing his extensive research and knowledge on air activity over the Channel Islands and the arrival of the occupying forces; Richard Heaume MBE for his advice, guidance and encouragement throughout the project; David Kreckeler for permitting reproduction of some of his work on the known escapes from German-occupied Guernsey and Alderney; to Pierre Renier for allowing us to use his research into Red Enigma, Boniface and the Y Service events of 27 June to 1 July 1940; and to both Pierre Renier and Steve Powell for access to their research on the government files relating to the invasion and occupation of the Channel Islands; to Michael Ginns OBE for kindly allowing reference to his research on Operation Green Arrow; Maggie Tablot-Cull for access to her fathers (Bill Greens) records; to Mrs. Bell, widow of the late William Bill Bell, for permission to reproduce excerpts from his books; to Sally Falla for permission to reproduce excerpts from Frank Fallas excellent book Silent War; to both Ken Tough and Paul Le Pelley; to the Committee of The Channel Islands Occupation Society Guernsey in allowing me to reproduce excerpts from their reviews and access to the Societys formidable archive; to the Island Archive Services, Guernsey; to Malcolm Woodland; to John Grehan at Frontline Books for his unstinting help and advice whilst compiling information for this book; to Martin Mace, my Publisher, for his guidance, encouragement and enthusiasm for this project; and to my family and friends for all of their support. Lastly, my thanks go to those who took the time to record daily life on the Channel Islands during the Second World War.

Introduction

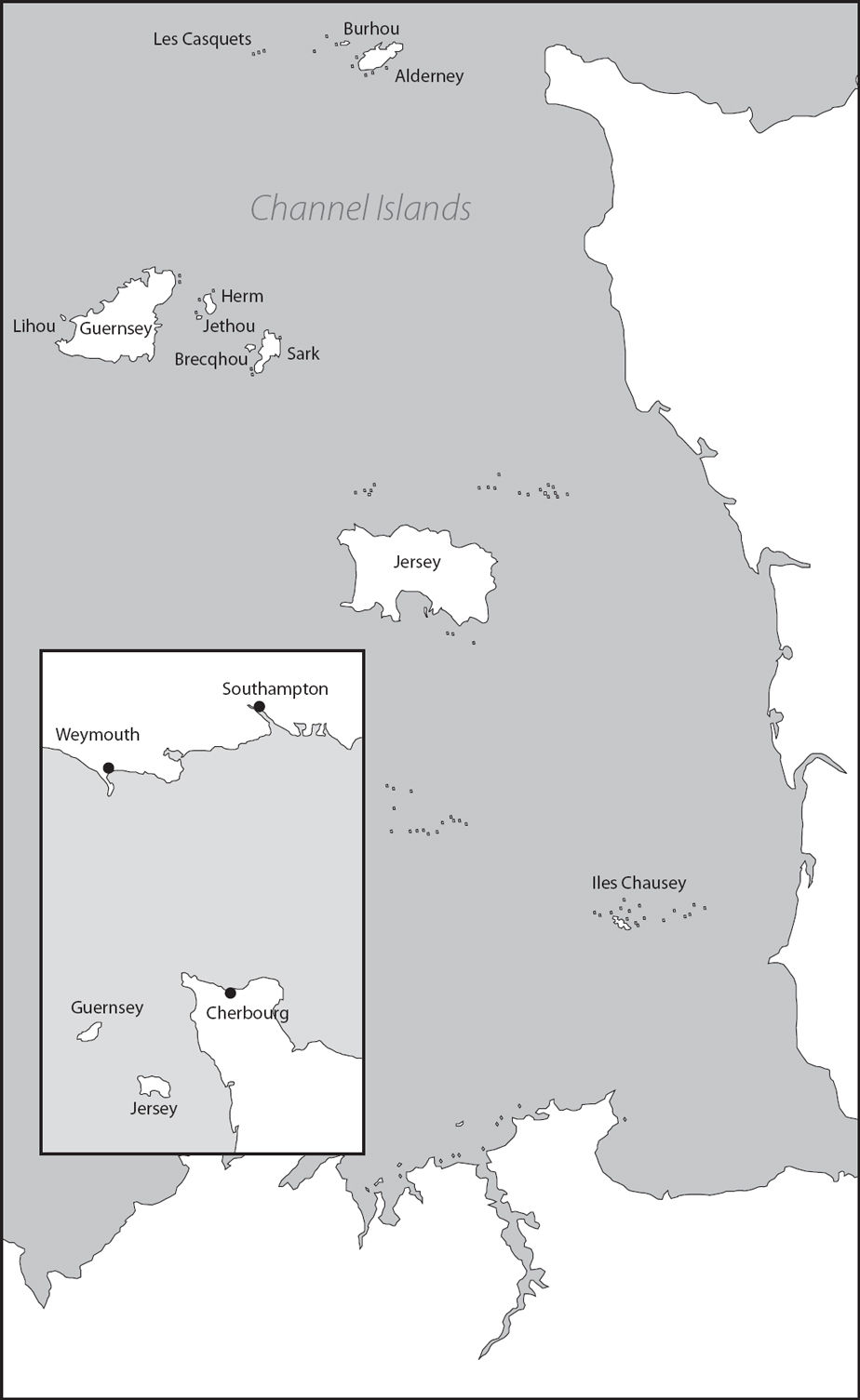

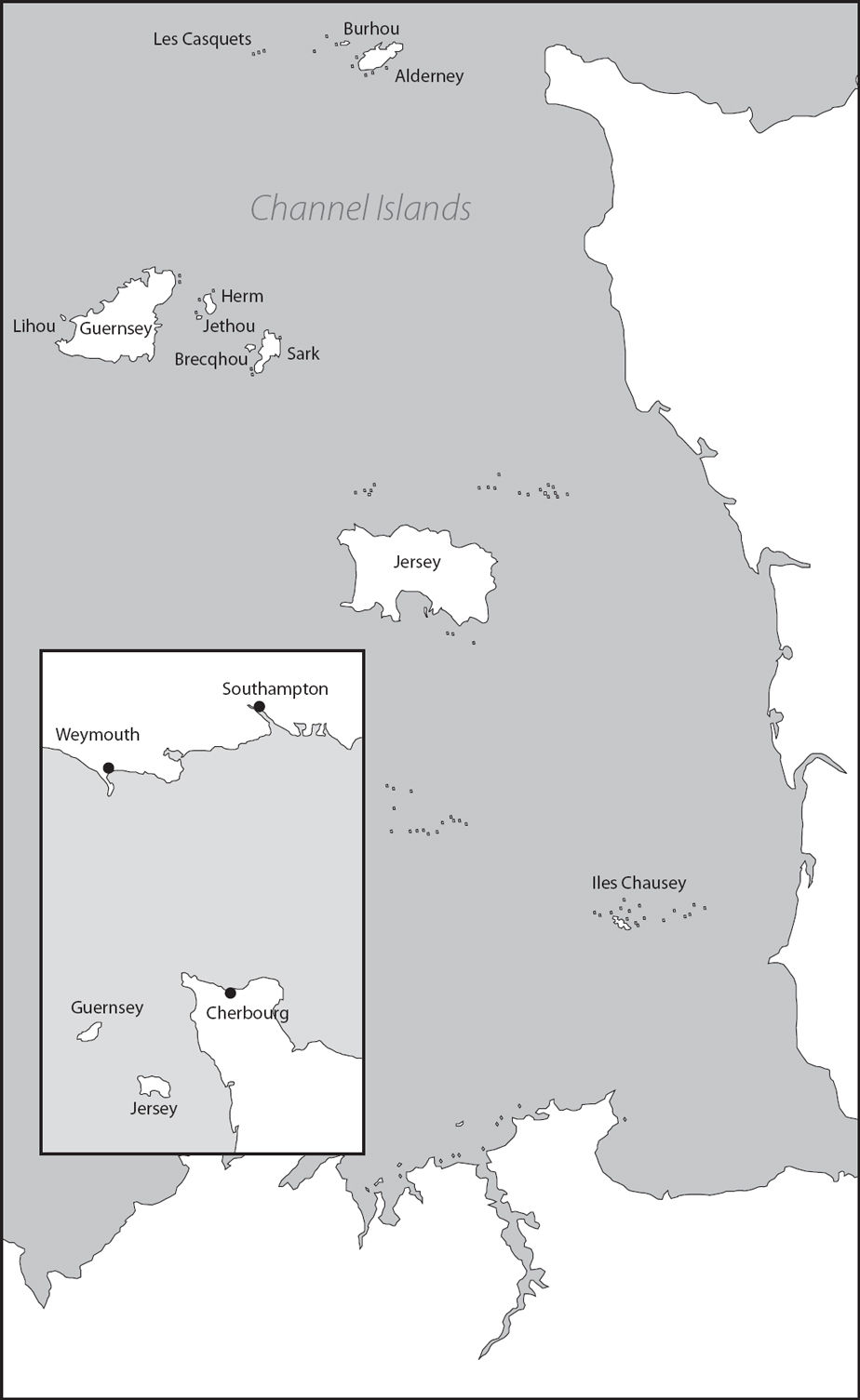

I n the summer of 1940 the British Isles stood isolated and alone facing the might of a seemingly unstoppable German war machine that had compelled France to submit and had driven the British Expeditionary Force off the Continent. Never before had the United Kingdom been in a state of such uncertainty and possible peril. Fortunately the full breadth of the English Channel held back Hitlers armies, and his ambition. Not so for the Channel Islands which stand just a few miles from the French coast.

The British Army and the RAF had lost heavily in the Battle of France. Every man and machine that had escaped back to the United Kingdom would be needed for the defence of mainland Britain. What then would happen to the Channel Islands?

This was the dilemma that confronted the newly-appointed Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, and his War Cabinet. To abandon British territory to the enemy was unthinkable, yet its defence was impracticable, if not impossible. Furthermore, if the Germans attempted an invasion and British troops resisted, the islands would be turned into a battleground, wreaking death and destruction upon the civilian population.

Should, therefore, the islands be completely demilitarised in the hope that the Germans would simply leave the strategically unimportant archipelago alone? But what if they didnt? What would happen to the tens of thousands of Islanders? Could Britain stand aside and watch these people whose lands had been Crown Dependencies for centuries be subjugated by the Nazi regime?

The alternative would be to evacuate the islands and transport their people to the UK. Yet, with a combined population of nearly 100,000, could this actually be done? Would this mass of evacuees then become more useless mouths to feed, joining the thousands of others who had already fled from the Blitzkrieg on Continental Europe for the relative safety of Britain. These were difficult questions and decisions that had to be faced and made by the UK Cabinet, Island Governments and every man and woman in the street and, in those dark days of May and June 1940, they needed to be made quickly.

For the Islanders themselves, the main conundrum was whether they should stay and hope for the best. If the Germans did arrive, what could they expect? The official guidance when it came, perhaps confusing at times, or simply confused through the nature of the prevailing situation, was to keep the islands running, but also, to safeguard the future, that women, children and men of military age were to evacuate. This, though, led to even greater heart-wrenching dilemmas. How could parents send their children away, husbands their wives, and wives their husbands? Conversely, how could they afford not to? Truly difficult times.

The Luftwaffes bombings of the two principal islands followed and left no one in doubt as to their fate the enemy was on the doorstep and about to kick the door wide open! How would these foreign troops treat the population on the first, and, as it transpired, only, bit of British soil to be captured?

This for me as a Guernseyman was an important story to be told and for many outside the Islands is a little known story. I myself grew up with a very keen interest in history which was sparked by my grandfather who was the first president of the Guernsey Ancient Monuments Committee, a position he held for thirty-three years. Visits to military installations and museums were a regular occurrence for me. In the 1980s I joined the Channel Island Occupation Society, through which I came to discover what I would describe as living history. I consequently spent many hours talking with people who lived during the German Occupation of the Channel Islands, and from that time I set out to research and record the Second World War history of this part of the British Isles.

There are many scores of books that have been written on this subject and although that history is being expanded and modified as our knowledge increases, the basic story remains unchanged. That story came from the mouths and pens of those who lived through the occupation, the ordinary men and women whose everyday lives were suddenly and irrevocably changed; through the politicians who had to make the, inevitably, invidious decisions and through the newspaper reporters who could freely comment and criticize.

Next page