For Nuala

INTRODUCTION

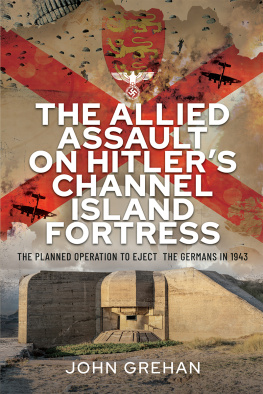

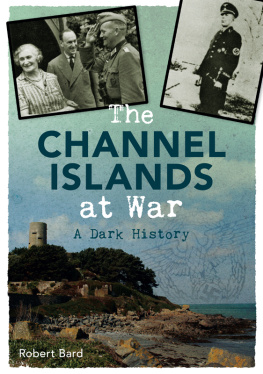

CUT OFF FROM THE MAIN

W HITEHALL

Wednesday 19 June 1940

Repugnant!

The prime minister spat out the word, glowering at the small group of men seated around him. Give up British territory to the enemy without a fight? It was unthinkable.

After just over a month in the top job, Churchill had grown accustomed to fierce arguments with the members of his war cabinet. Only three weeks earlier, he had seen off an attempt by his foreign secretary, Lord Halifax, to open peace negotiations with Germany using Mussolini as an intermediary. Then, a combination of dogged determination, inspired oratory and wily political manoeuvring the PM had summoned an impromptu meeting of his entire, twenty-five-man cabinet to provide a more responsive audience for a typically barnstorming speech had carried the day.

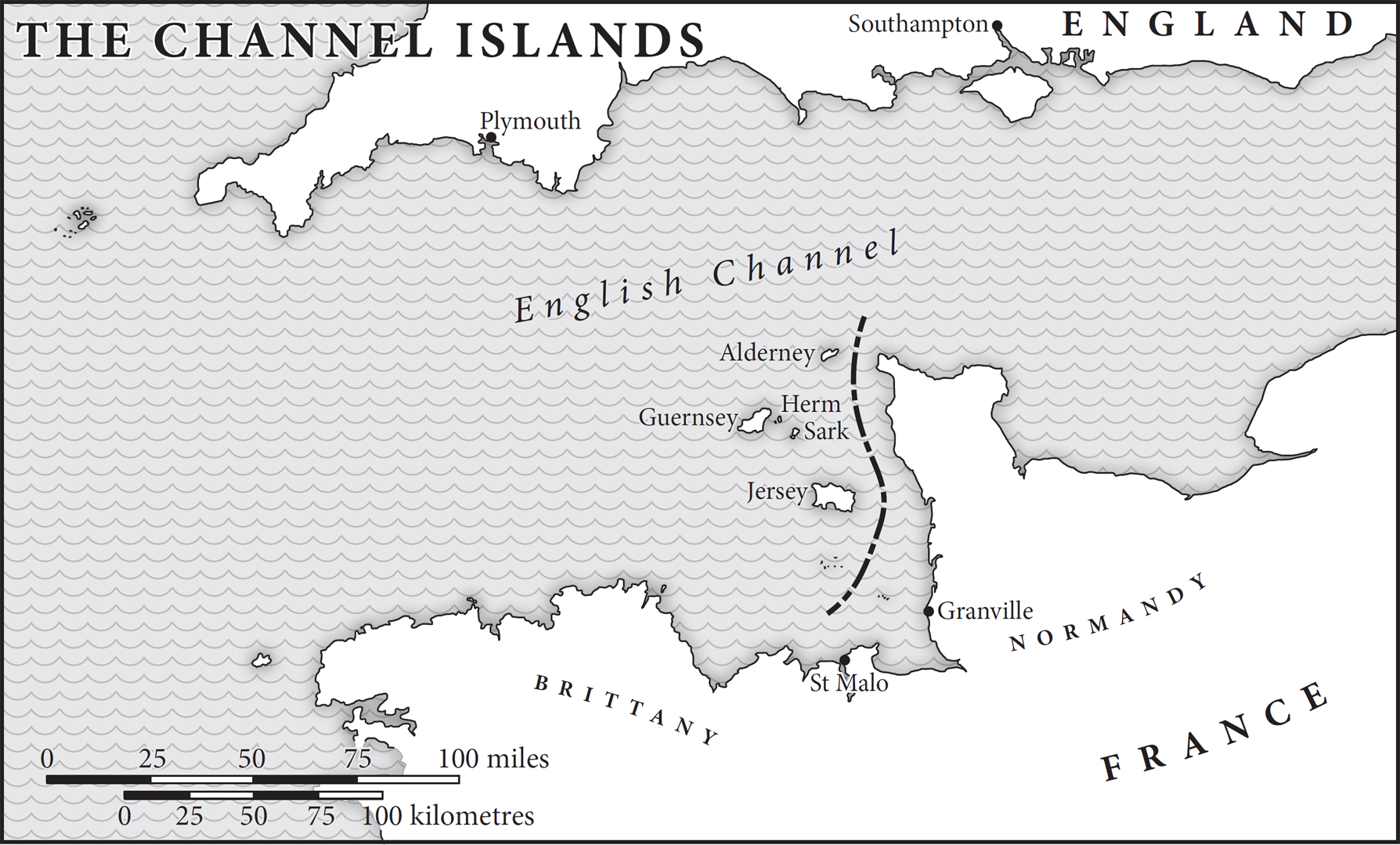

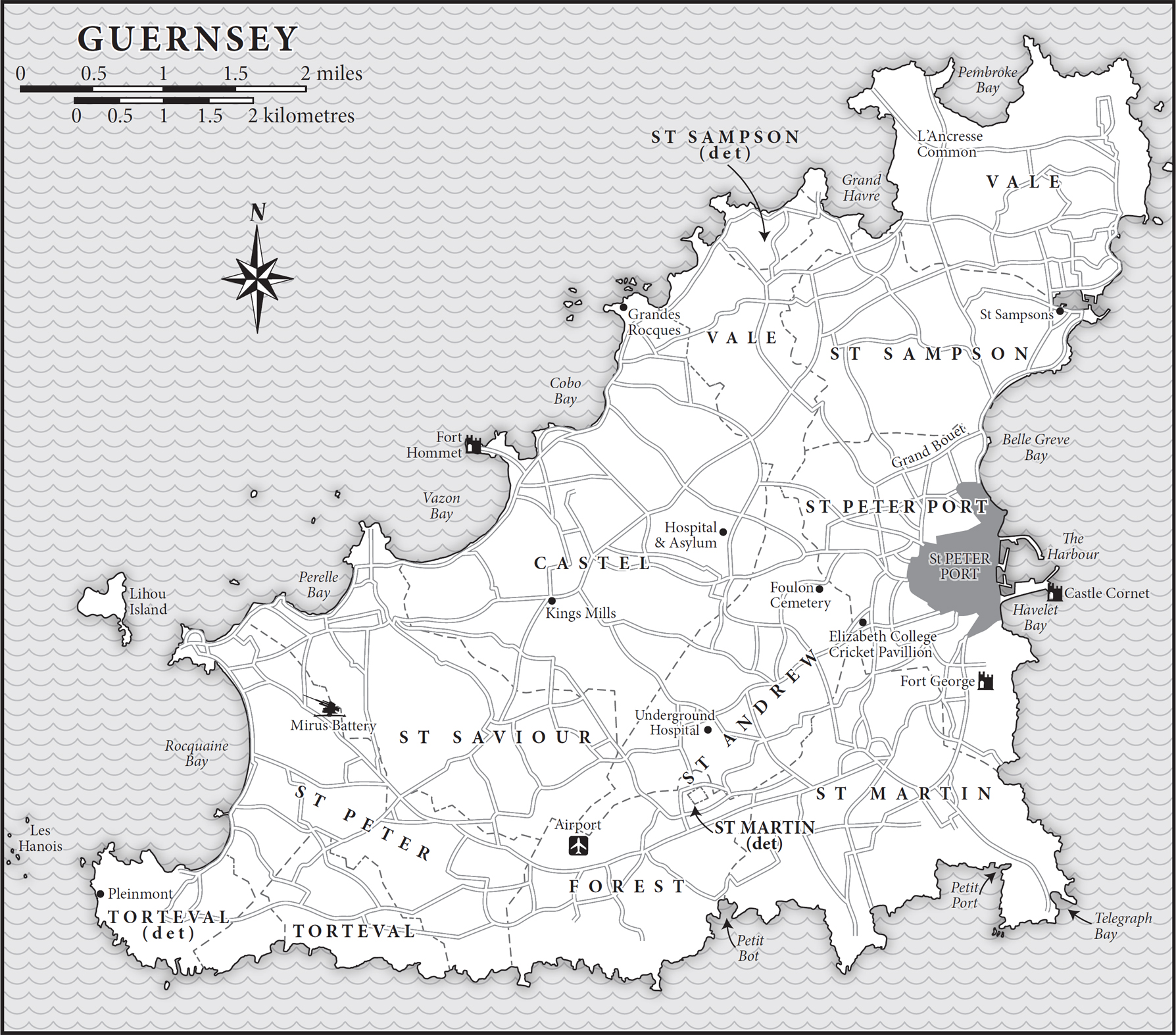

This time it was the Chiefs of Staff who had brought Churchill a distinctly unappealing proposal. With the German Army now occupying the coast of France, the time had come, they believed, to withdraw their forces from the Channel Islands, an archipelago off the coast of Normandy that was home to more than ninety thousand British subjects. The islands were, they concluded, not of major strategic importance, and defending them was more trouble than it was worth.

Churchill was horrified. The Channel Islands had been dependencies of the Crown for the better part of a thousand years. Whatever their strategic value or lack of it as far as he was concerned, holding onto them was a matter of principle. After all, wasnt he the man who had promised to fight on the beaches and never surrender? The prospect of German jackboots falling on British soil and without a single shot being fired hardly chimed with that impassioned pledge.

Before becoming prime minister, Churchill had spent five years as First Lord of the Admiralty. Surely, he declared, the Royal Navy ought to be able to defend the islands from the enemy. If there is a chance of offering a successful resistance, he argued, we ought not to avoid giving him battle there.

But the response from the vice-chief of Naval Staff was not encouraging. The islands were too far away from the British mainland, and too near to enemy bases at Brest and Cherbourg, for naval forces to adequately protect them, he explained. Added to which, the necessary material simply wasnt available if anti-aircraft guns and fighter aircraft were deployed to the islands in the numbers required, it would leave the coast of England vulnerable to attack. To put it bluntly, the Channel Islands could only be defended at grave risk to the security of the mainland.

Put that way, there was really no choice. Whether the islands were expendable or not was no longer the issue. They simply werent worth losing the war over.

That summer, losing the war was looking like a very real possibility. The blitzkrieg, or lightning war, unleashed on France, Belgium and the Low Countries had more than lived up to its name. In six blistering weeks, the Wehrmacht had swept through Europe, bringing nation after nation to its knees. Only two days before the war cabinet meeting on the Channel Islands, France had joined Belgium, Holland and Denmark in requesting an armistice, well aware that this would mean long-term occupation by the Germans.

With every one of her former allies now under the Nazi yoke, Britain alone remained in the fight against Germany and the odds were not in her favour. She had an army less than a third the size of the enemys, and a population only half as large from which to draw new recruits. There was no doubt that an invasion of Britain was already in Hitlers sights, and short of outright surrender, there seemed little chance of avoiding it.

Since the British Expeditionary Forces scramble to safety from the beaches of Dunkirk a fortnight earlier, the British public had caught their first glimpse of what a German invasion might mean. In the wake of the exhausted, demoralised and bedraggled soldiers who stepped off the little ships came a stream of pitiful refugees tens of thousands of ordinary civilians whose homes had been overrun by the German Army, and whose lives had already been destroyed thanks to the apparently invincible war machine. Many of those who saw them couldnt help wondering if the wretched state of the new arrivals was a premonition of what was to come when the Germans finally landed on their own soil.

On both sides, preparations for the expected invasion were beginning to get underway. The German Army, Navy and Air Force had been discussing possible strategies since the previous December. Now, following the fall of France, the German High Command began to draw up more definite plans, under the code name Operation Sea Lion. I have decided to prepare for an invasion, Hitler wrote in his Directive No. 16, intended to eliminate England as a base for carrying on the war against Germany and, should it be required, completely to occupy it. Once the RA F had been pummelled into submission by the Luftwaffe, the plan was for over a quarter of a million men to be landed in a matter of days enough to seize the country for the Fhrer, and put an end to the war once and for all.

In Britain, ordinary people were readying themselves for the expected onslaught. Almost half a million men aged from seventeen to sixty-five had already enrolled as Local Defence Volunteers (not yet rebranded as the Home Guard) and were practising making Molotov cocktails to hurl at German tanks. Up and down the country, temporary roadblocks had been prepared using tree trunks, abandoned cars and carts full of builders rubble, and fields where enemy aircraft might land had been peppered with obstacles too. The Petroleum Warfare Department was looking into ways of repelling an enemy fleet by setting the sea itself on fire.

The day before the war cabinet meeting on the Channel Islands, Churchill had told the British people to prepare themselves to face the whole fury and might of the enemy, and to brace themselves for a battle that would be remembered for a millennium as the nations finest hour. As the prime minister delivered his speech in Parliament, government printing presses were rattling off 1.5 million copies of a leaflet entitled If the Invader Comes, to be distributed up and down the country over the next few days. Think always of your country before you think of yourself, it declared firmly.

Privately, many civilians were starting to wonder how they would cope if the Germans came knocking on their door. Some resolved to commit suicide, ideally taking a few of the invaders down with them a wealthy lady in Buckinghamshire planned to invite a group of officers in for champagne laced with weed killer. Others felt they could do their bit by depriving them of valuable supplies. The government had advised homeowners to hide maps, bicycles, petrol, even food. At a Dorset branch of the Womens Institute, there was a spirited debate about how to prevent their large stock of home-made jam from falling into enemy hands. Some members felt that every jar should be smashed to smithereens, others that merely hiding them under the floorboards was sufficient.