First of all I would like to thank the leaders, staff and members of the vast majority of the movements in this book for their cooperation, their willingness to answer my questions and their permission to quote them. Thanks also to the writers and copyright holders of all the books, essays, lyrics, magazines, booklets and websites I have quoted.

The staff at the British Library, the British Library of Political and Economic Science, the Wellcome Library and Inform, the research centre for new religious movements at the London School of Economics, have, as always, been helpful and efficient. The website http://www.sacred-texts.com is also a splendid resource for any writer on religion.

Most sociologists and anthropologists see participant observation as an invaluable research tool. By spending time with members of movements one can gain not just knowledge but understanding, not just facts but insight. Over the last decade or more the London esoteric scene has made me welcome and has included me in many of its activities, knowing that I am a researcher and writer and not a member of any esoteric movement myself. Over the same period I have benefited greatly from listening to and questioning other researchers and speakers, and also from questions, comments and criticisms from the audience when I have been the speaker, both at academic seminars and conferences and in meetings in upstairs rooms in pubs. All of these have been immensely valuable; I owe a lot to them.

The seminars include Inform conferences and many postgraduate seminars at the London School of Economics, and also at Goldsmiths College, Kings College, Senate House and the School of Oriental and African Studies, all parts of the University of London. The meetings include, in alphabetical order, London Earth Mysteries, the Moot with No Name, Pagan Federation conferences and open rituals, Research into Lost Knowledge Organisation, Secret Chiefs, Skeptics in the Pub, the South East London Folklore Society, Talking Stick and UnConvention.

There are also a number of people, many of them friends and colleagues and a few I have never met, whom I would like to thank by name. Between them, in conversation and by email, they offered invaluable suggestions and criticisms on my text, and/or were willing to give up their time to talk to or email me about their beliefs and practices for the What I Believe panels. In alphabetical order: Dolores Ashcroft-Nowicki, Geraldine Beskin, Dr Jenny Blain, Dr William Bloom, Philip Carr-Gomm, Chic and Tabatha Cicero, Ina Csters-van Bergen, Terry Dobney, Ken Eakins, Dr Dave Evans, Jack Gale, Dr Graham Harvey, Professor Ronald Hutton, Stuart Inman, Professor Jean La Fontaine, Gareth J. Medway, Mani Navasothy, Dr Paul Newman, Dr Christina Oakley Harrington, Phil Parkyn, Jon Randall, Dr William S. Redwood, Emma Restall Orr, Steve Wilson, Dr Michael York and Oberon Zell-Ravenheart. My thanks also to Howard Watson for his excellent copy-editing of the text.

Between them they have helped make this book much better than it would otherwise have been, but they are not responsible for any remaining faults.

For anyone who writes about the variety of religious movements it is dispiriting that a decade into the new millennium it is still necessary to point out that Wiccans are not Satanists.

Journalists writing an attention-grabbing story equating witches with black magic with Satanism either havent done their homework, or dont care why let the facts get in the way of a good story?

Fundamentalist Christians who do the same have a different reason: any belief which is not of Christ must necessarily be of the Devil He that is not with me is against me (Matthew 12:30) so all Neo-Pagans are by definition Satanists, whether they think they are or not. The fact that the same logic would also apply to Buddhists and followers of every other religion is usually ignored.

Christians in particular shy away from the word occult as though it must have devilish connotations. In fact, the word simply means hidden or secret (see p. 13), and since many of the traditional occult teachings are now widely available indeed, many of the esoteric or occult schools now have websites explaining their purpose the term no longer really applies.

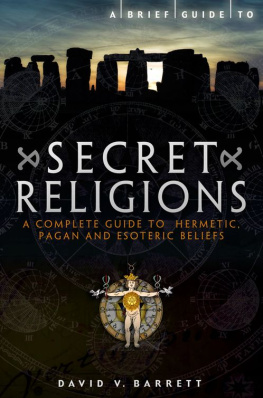

This book is in many ways a companion volume to my A Brief History of Secret Societies, But they are all alternative religions, outside the mainstream, and many of them keep their beliefs and practices to themselves.

One of the books main aims is to dispel many of the popular misconceptions about New Age, Hermetic and Neo-Pagan beliefs and their believers.

I entitled an earlier book on new religious movements The New Believers

As with all my books I aim to bring a scholarly approach to the content, while avoiding the dryness of far too many scholarly books; this book is written for anyone with an interest in these religions, whatever their academic background.

The monotheistic religions in general have problems with religious pluralism; they believe that there is not only one god but one truth, and that each one of them alone has it. In contrast, esoteric religions, again in general, tend to think in terms of paths; someone may choose one path for himself, but will not only respect the right of other people to choose their own paths, but also accept the validity of those other paths. Many occultists and Neo-Pagans are polytheists, but even those who focus on one god are most likely to be henotheists, following one god but happily accepting the existence of others.

Esoteric religions do not enjoy the same respect from others that mainstream religions usually do. In religiously conservative America a Republican Senate candidate in the 2010 mid-term elections felt that she had to begin a political advertisement with the words Im not a witch because in 1999 she had said in a TV chat show, I dabbled into witchcraft. (see p. 248, p. 280).

It is partly to counter such inflammatory remarks that this book has been written. It covers a large number of movements and a large number of beliefs. It does not assume that any one of them is right and all the others are wrong; that is the antithesis of most esoteric thinking, particularly in Britain and Europe. It does not judge the spiritual truth of any of the movements though it may sometimes question their histories.

The book does not set out to be an encyclopedic directory of all esoteric movements; that would be impractical and unwieldy, if not impossible to do. Neither is it an apologia for the groups included, though some might have wished it to be so.

It is instead an overview of a wide range of esoteric movements , describing their origins and history, their beliefs and practices, and sometimes their controversies. One of the themes running throughout the book, for example, is the uncertain provenance of many groups and the uncertain backgrounds of some of their founders (see p. 1834, p. 197, p. 3001). The book aims to help readers to distinguish between factual history and mythic history in a number of cases.

Although the song The Age of Aquarius, from the 1967 musical Hair!, promised the Sixties ideal of peace and love, with harmony and trust, the reality of New Age, Hermetic and Neo-Pagan movements has often been anything but, with schisms, accusations, recriminations, lawsuits and sometimes outright deceptions. These are all part of the colourful tapestry woven by esoteric movements not just in the last few decades but over more than a century though they are, of course, not unique to esoteric religions.