Barrett - Agrippina: mother of Nero

Here you can read online Barrett - Agrippina: mother of Nero full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: London, year: 2005;2011, publisher: Routledge;B. T. Batsford, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

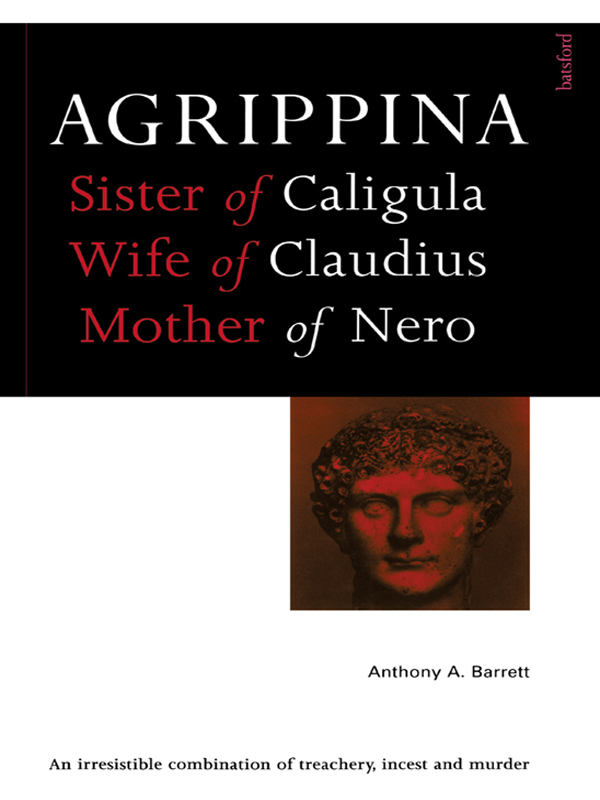

- Book:Agrippina: mother of Nero

- Author:

- Publisher:Routledge;B. T. Batsford

- Genre:

- Year:2005;2011

- City:London

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Agrippina: mother of Nero: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Agrippina: mother of Nero" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Agrippina: mother of Nero — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Agrippina: mother of Nero" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Anthony A.Barrett 1996

First published 1996

This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005.

To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledges collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission from the Publisher

Published by B.T. Batsford Ltd

4 Fitzhardinge Street, London W1H 0AH

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 0-203-48106-2 Master e-book ISBN

ISBN 0-203-78930-X (Adobe eReader Format)

ISBN 0 7134 6854 8 (Print Edition)

The jacket illustration shows a sculptured head of Agrippina (Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen).

Through some perverse and mysterious quirk of nature, the villains of history, rather than the saints, are what excite the popular imagination. Characters like Rasputin, Dr Crippen, Vlad the Impaler are undoubtedly evil, but they are also so colourful and so alluringly sinister, that they fascinate at the same time as they repel. At first glance Agrippina the Younger clearly deserves membership in this select company. She plotted against her brother Caligula (as well as sharing his bed), she murdered her husband Claudius with a deadly mushroom, and she tried (unsuccessfully) to cope with a rebellious teenage son, Nero, by sharing his bed too. She was finally eliminated by that same Nero through a scheme as ingenious and outlandish as any in the history of crimean irresistible combination of treachery, incest and murder. Or so tradition has it. Whether these things actually happened is another matter altogether. At one level it makes hardly any difference, since historical reputations are a product of perception, not of reality. But at another level the issue is an important one. The complete truth about Agrippina may be unobtainable by now, but the serious reader is entitled to hope for a version that comes as close to that truth as the evidence allows, rather than a string of entertaining but dubious anecdotes. That kind of sober reappraisal of the evidence is the objective of this biography.

Time has certainly not been kind to Agrippinas memory. She suffers one accidental disadvantage, essentially trivial but often a curse on posthumous reputations. She had a parent of the same name, not as famous (infamous in her case) but prominent enough for the activities of mother and daughter to be occasionally confused. Far more serious, Agrippinas sordid popular image has eclipsed her more significant accomplishments. Along with Livia, the wife of the first Roman emperor, she represents a political paradox of the early Roman empire, the woman who managed to exercise great power and influence in a society that offered no constitutional role to powerful and influential women. It is this achievement, to be empress in an empire that allowed only emperors, that makes her accomplishments interesting and worthy of serious study. But not to the Romansthey saw the elevation of women like Agrippina as an inversion of the natural order, and the preoccupation of the ancient writers with the evils of female ambition all but blinded them to any admirable qualities they might have possessed.

Modern scholars, of all national backgrounds, have with very few exceptions treated Agrippina no less harshly than did their ancient counterparts. In the first monograph devoted to her, Agrippina die Mutter Neros, written in German over a century ago, the distinguished writer Adolf Stahr accepted the hostile ancient testimonia uncritically. More recent treatments have maintained this tradition. Syme calls her violent, truculent and merciless, corrupt but vigorous and speaks of her robust criminality. To Dudley she is a Clytaemnestra of a woman. Mellor considers her loathsome and treacherous, and complains of her murderous immorality. Fabia calls her dure, vindictive, impitoyable. Lackeit, in the entry on Agrippina in the influential Paulys RealEncyclopedie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft, portrays her as a depraved and power-hungry monster, who exercised a demonic influence over her husband and son. The excellent brief study by Werner Eck, Agrippina, die Stadgrnderin Klns, is on the whole more balanced, but he still portrays her as an essentially ruthless woman. Modern scholars generally share the revulsion felt by the ancients towards a woman who presumed to be ambitious and was therefore greedy for power (Dudley), driven by orgueil ambitieux (Fabia) or ehrgeizigen Streben (Domaszewski).

The actual record, however, suggests very strongly that both ancient and modern writers offer a lop-sided portrait, at best. Agrippinas presence seems to have transformed the regime of her husband, the emperor Claudius. Only a secure ruler can be an enlightened ruler. She appreciated that such security depended on the loyalty of the troops, especially the praetorian guard garrisoned in Rome. This much, admittedly, involved no great insight, but her cleverness lay in recognizing that it was not enough to control their commander, who might be removed peremptorily; she also hand-picked the middle officers, and through them kept a secure grip on the rank and file. In addition, she understood that, while senators in Rome might not command armies, they did, more than any other group, represent the pride and traditions of the old republican Rome. Coercion and force could make them servile, but also sullen and dangerous, while diplomacy and tact would mould them into helpful collaborators. Similarly, the one colony founded under her sponsorship, Cologne, stands out as a remarkable instance of co-operation between the Romans and the local population. The evidence suggests that after her marriage to Claudius, Agrippina inverted the normal progression of a monarchical regime, changing it from a repressive dictatorship marked by continuous judicial executions to a relatively benign partnership between the ruler and the ruled. Also, the ascendancy she enjoyed after her son Neros accession coincided with the finest period of his administration, and her final departure from the scene seems to have removed the restraining check to his descent into erratic tyranny.

Thus Agrippinas contribution to her time seems on the whole to have been a positive one. This does not mean, of course, that she was a paragon of virtue and a woman of sterling character, worthy of the devout and unstinting admiration bestowed on her by her one major apologist, Guglielmo Ferrero. Writing at the beginning of this century, Ferrero portrayed her as a splendid heroine of duty. In fact, the evidence, honestly and fairly evaluated, seems to suggest that she was a distinctly unattractive individual. But in her defence it might be pointed out that politically ambitious people tend not to be appealing at the very best of times. And politically ambitious people who have to make their way in a monarchical system can generally succeed only through behaviour that is by most norms repellent. If we add to this formula a politically ambitious woman in a monarchical structure that had no formal provision for the involvement of women, the odds are almost insurmountable in favour of her being, by necessity, rather awful. It is when Agrippina is judged by her achievements, rather than by her personality or character, that she demands admiration.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Agrippina: mother of Nero»

Look at similar books to Agrippina: mother of Nero. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Agrippina: mother of Nero and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.