PRAETORIAN

Copyright 2017 Guy de la Bdoyre

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publishers.

For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, please contact:

U.S. Office:

Europe Office:

Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd

Printed in Great Britain by Gomer Press Ltd, Llandysul, Ceredigion, Wales

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016958591

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 2379), known to us as Pliny the Elder, author of the Natural History, has been a personal inspiration for years. His belief that to be alive is to be awake, and that everything is of interest and everything worth exploring, combined with a relentless and unassailable curiosity, made his life the model for open-mindedness and enquiry without any sense of boundaries. Todays world of education could learn a great deal from him.

I would also like to dedicate this book to my first grandchild, Eleanor (Nell) Rose de la Bdoyre, born at exactly the time it was finished in the early summer of 2016, and to my mother, Irene de la Bdoyre, whose love of history was always an inspiration and who died in July 2016 at the time this book was delivered to the publisher.

CONTENTS

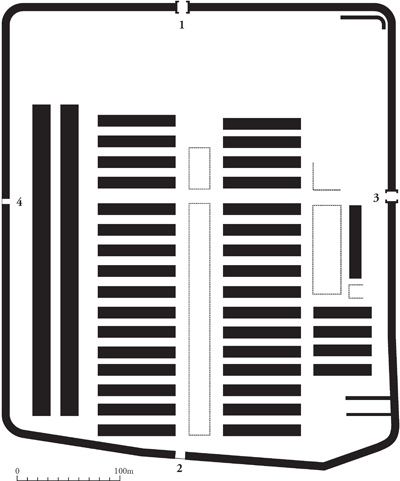

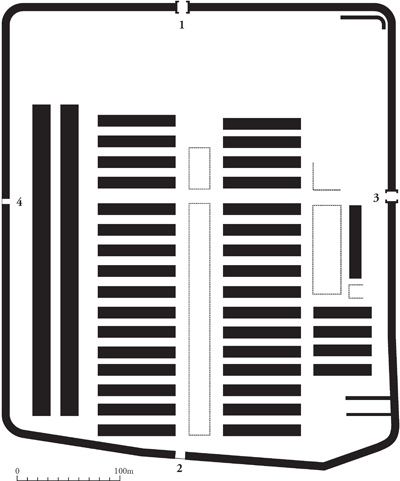

Plan of the Castra Praetoria

The area of the praetorian camp was 41.2 acres (16.72 hectares). The west and south walls were demolished by Constantine along with the west and south gates. Their exact positions are now only hypothetical. The main road through the camp, the Via Principalis, ran between the north and south gates. The kink in the south wall is explained by the need to conform to existing road alignments. Only fragmentary traces of barracks have been identified, so the blocks shown here are largely hypothetical, too. Even this incomplete plan shows the marked difference from a conventional fort because of the apparent lack of major buildings such a headquarters premises (principia) and commandants house (praetorium). Blank areas are only zones where nothing has yet been found due to lack of exploration; they are not indicative of open areas in antiquity.

1. Porta Principalis Dextra (north)

2. Porta Principalis Sinistra (south)

3. Porta Decumana (east)

4. Porta Praetoria (west)

1. Camp gate.

Fragment of marble relief now close to the Portico of Octavia, depicting a stylized fort with gates. The way the fortifications have been used as a wreath surrounding a victorious eagle atop the globe symbolizes the Roman states militarized identity. It is possible it represents the Castra Praetoria, but may well be of earlier date.

2. Philippi Praetorian coin.

Of uncertain date and purpose, but probably struck between 27 BC and AD 68, this bronze issue produced at Philippi appears to commemorate the battle of 42 BC. It also seems to honour the praetorians either at the battle or as settled veterans in the colony established by Augustus. The coin depicts three praetorian standards and the legend COHOR PRAE PHIL.

3. Castra Praetoria north gate.

The Castra Praetorias north gate Porta Principalis Dextra, filled in probably by Maxentius, is still quite easily visible from across Romes Viale de Policlinico. Like the east gate, and probably also the south and west gates, it was single-portalled. Three filled-in windows are noticeable in the gate tower. The remains are of multiple periods including the Tiberian lower walls, the gate tower of c. 238 and the upper sections from c. 2705.

4. Castra Praetoria north wall.

Close-up view of a section of the Castra Praetorias north wall showing how the original 3.35-metre wall with crenellations was subsequently raised to 5 metres by the simple expedient of filling in the crenellations and building upwards. The walls exhibit evidence of numerous modifications, repairs and heightening.

5. Castra Praetoria NE corner.

The Castra Praetorias north-east corner retains its tower and also evidence of the precautions taken by the Tiberian builders of the original structure. A weight-relieving arch is clearly visible at the bottom, designed to help stabilize the wall on unreliable patches of ground.

6. Sejanus coin, Bilbilis.

Bronze coin of Tiberius issued at Bilbilis, Spain. On the reverse, the names of the two consuls in Rome for the year 31 are given, in this case the emperor and also Lucius Aelius Sejanus, the then praetorian prefect. This is a unique instance of a serving praetorian prefect being recorded this way.

7. Temple of Apollo, Palatine Hill, Rome.

These fragments are all that is left of the Temple of Apollo on the Palatine Hill. It was here, on 18 October 31, that the senate was gathered when Sejanus was tricked by Macro into attending, in the belief that he was to be promoted. As Tiberius speech was read out, it became clear he was in fact being publicly denounced.

8. Temple of Concordia Augusta, Rome.

The foundations to the right mark all that remains of the Temple of Concordia Augusta. Shortly after the arrest of the praetorian prefect Sejanus on 18 October 31, this was where the senate met and condemned him to death. Behind is the Tabularium (record office), now part of the Capitoline Museum, and, to the left, the remaining columns of the Temple of Vespasian and Titus.

9. Tombstone of Agrippina the Elder.

The tombstone of Agrippina the Elder, granddaughter of Augustus, daughter of Agrippa, wife of Germanicus, and mother of Caligula. Beloved by the army, when she returned to Italy with her husbands ashes in 19 she was met by two praetorian cohorts at Brundisium, who accompanied her to Rome. She died in 33. Her ashes were deposited in the Mausoleum of Augustus, from which this stone comes.

Next page