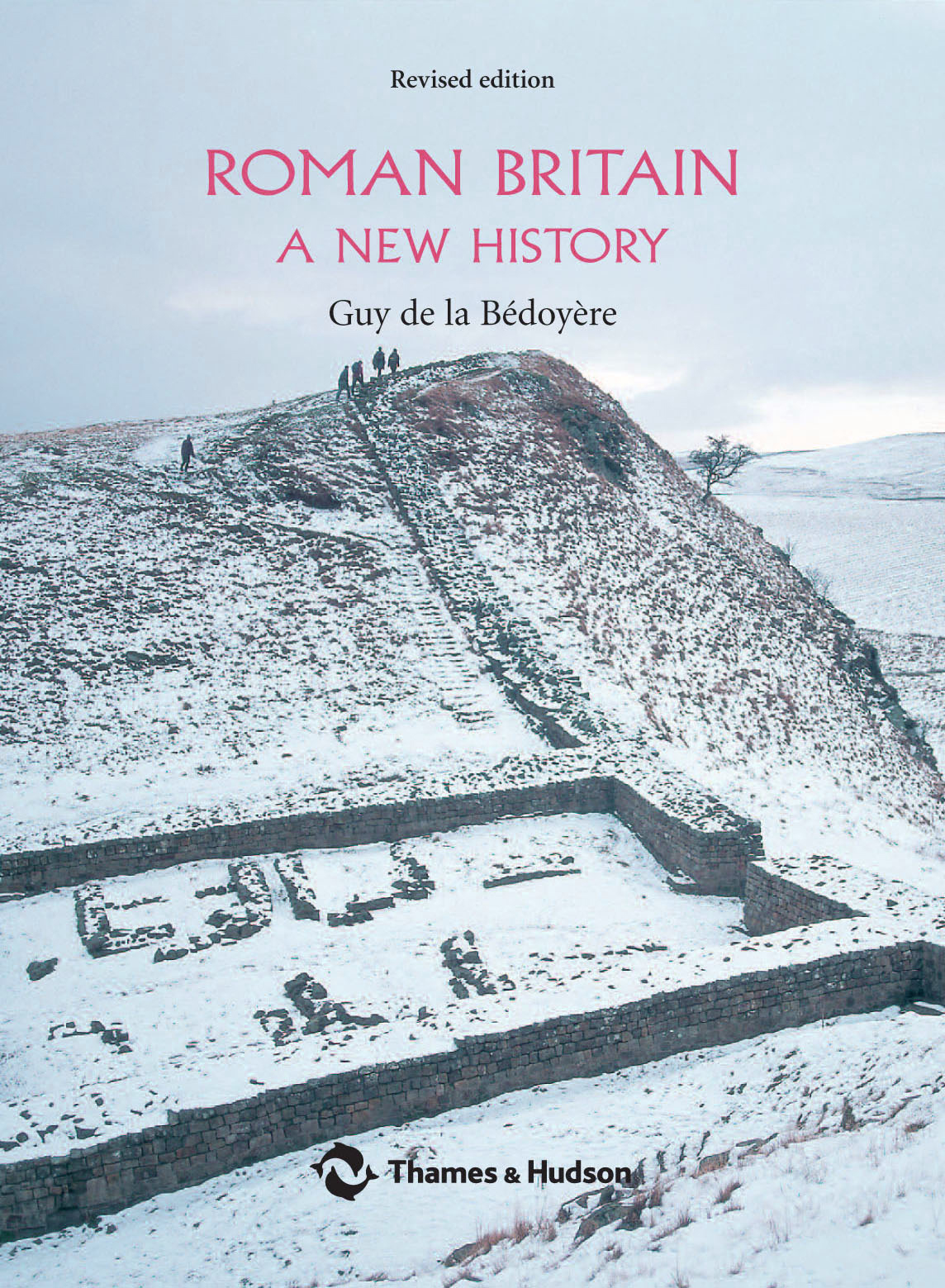

ROMAN BRITAIN

A NEW HISTORY

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Guy de la Bdoyre has become one of the public faces of Romano-British history and archaeology through his many appearances on several television programmes, particularly Channel 4s Time Team and Big Roman Dig, which he co-presented. He is the author of numerous books on the period, including Eagles Over Britannia (2011), Roman Towns in Britain (2003) and Cities of Roman Italy (2010).

Other titles of interest published by Thames & Hudson include:

Chronicle of the Roman Emperors: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers of Imperial Rome

Chronicle of the Roman Republic: The Rulers of Ancient Rome from Romulus to Augustus

The Complete Roman Legions

England: A Concise History

Legionary: The Roman Soldiers (Unofficial) Manual

The Origins of the Irish

Roman Art and Architecture

Rome in the Ancient World: From Romulus to Justinian

The Romans Who Shaped Britain

See our websites

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

CONTENTS

Roman Britain was Britains first truly historical period, and as such it has deservedly been the subject of many books, especially in the last thirty years. Today, thanks to excavations, scientific techniques and new research, we know far more about this unique mixture of classical and Celtic civilization. However, the basic history has not altered much. Instead it is the archaeology that has changed, and with it there has been a reappraisal of the architectural, material and social structure of Roman Britain. In the process, the history has become a little lost, or at any rate taken for granted.

Some of the greatest excavations of Romano-British archaeological sites were conducted in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. These included the work at Silchester and numerous digs along Hadrians Wall, and at other military sites nearby. The techniques of the time meant many features in the ground went unnoticed, whilst contemporary attitudes had their own effect. A preoccupation with the Roman army in Britain was common, and lay to a large extent in personal experience of Britains own imperial armed forces. Military documents found at Vindolanda in the 1970s show that the Roman army was far from being the rigid and predictable organization archaeologists once assumed, and probably also reflect other aspects of the way Roman Britain and other provinces were managed.

1. Gresham Street (London).

This bronze cauldron was found in a well at Gresham Street, constructed c. AD 100. After the well was destroyed by fire, it was back-filled with rubbish, including this cauldron, perhaps used initially for collecting water.

Perhaps this mirrors how our world has also changed. Equally, each generation of historians and archaeologists wants to make its mark. Part of this process is a ritual re-examination of some of the assumptions and attitudes of previous generations. An old dogma is supplanted by a new one. But just as the certainties of older scholarly attitudes now seem easy to question, we also need to bear in mind that the certainties of our own time are just as likely to be flawed. Today, dendrochronology and other modern archaeological techniques are often treated as infallible sources of objective information. Archaeologists also sometimes infer more from their excavations than the evidence can really support. The reality is that flawed historical and literary material cannot be made good by archaeology, not least because the evidence is of an entirely different kind. The two complement one another, but they are not mutual substitutes.

Even so, the archaeological record has been transformed. New techniques have made it possible to recognize environmental evidence in unprecedented detail, or to identify occupation levels that would entirely have escaped the notice of a Victorian archaeologist. Despite its usefulness, the metal-detector is regretted by many archaeologists because of the reckless way some detectorists have used it. However, some extraordinary finds have changed our view of Roman Britain forever. The fact that some finds have turned up in places that archaeologists either would not, or could not, have looked only goes to show how selective the official record can be. The Mildenhall Treasure (see ), found in the 1940s, was even thought by some at the time to have been a modern import from North Africa. Since then, the discovery of exceptional treasure hoards such as Thetford and Hoxne, along with a very large number of minor finds, have radically altered our knowledge of the sheer quantity of Romano-British sites. The remarkable coinage of the rebel emperor Carausius (28693), with its dramatic series of unprecedented mythical and literary types, was once rare. Now far more is known about this emperor from his numismatic record.

2. Crosby Garrett (Cumbria).

Found in 2010, this copper-alloy cavalry sports helmet was probably worn by an auxiliary trooper during ceremonial displays of military skills and re- enactments of legendary battles. A griffin sits atop the Phrygian cap headpiece. The helmet was sold at auction for 2.3 million in October 2010. First to third century AD.

Archaeology and history belong to their own time. Today, old certainties have been replaced by doubt, and a palpable fear for the future. A parallel often drawn today is how the increase in American power mirrors Romes rise, and how America has come to define todays world order. Now that international terrorism and environmental concerns have challenged our sense of security, it becomes easier to see what the dramatic decline of Roman power in the West in the fourth century meant for the Empires population. Likewise, an increasing focus on native identities in Roman Britain reflects an increased respect for ethnic identities in our own time. Imperialism has increasingly become condemned as a purely oppressive force, given weight by its appalling excesses in the twentieth century, and reinforced by a contemporary sense of the victim. Yet life is rarely quite so simple. The complex relationships between native society and Roman culture in Britain were just that, and evidently reached some sort of equilibrium which was surprisingly stable, and which seems to have been eventually acceptable to most of the participants. A new approach to the late Iron Age has made a very good case for the idea that some tribal aristocracies welcomed, and even coveted, Roman influence.

Archaeology has also been transformed in modern times. What was once the preserve of an exclusive few has become the everyday fare of popular television, magazines and weekend relaxation. Far more people now have access to the subject, with many seeking to further their knowledge as students. Others take part in excavations, often paying for the privilege of instruction in the field. Roman Britain is an especially popular component in this new world of archaeology. The Roman world is one that we can recognize, with its towns, roads, political structure, economy and multicultural society. Like all the most absorbing historical periods, it is at once a mirror for our own lives, and a portal into an age of mystery and intrigue.

Next page