C ONTENTS

L IST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

AND TABLES

Text figures

Colour plates

Tables

W riting a book is a great undertaking, and one which could have only been achieved with the help and support of my family, friends and colleagues. I would like to extend my thanks to the following individuals and organisations for making this volume possible: Dr Henry Blythe and Dr Alan Williams; John Frew for his cheerful help with sample preparation, testing and photography over the years; Barry Winfield, Heather and Owen Hazelby, and Laura Dodd.

Alan Wilkins for his help with the classical texts; Cohort Secundo Augusta and David Richardson for their generous permission to reproduce colour plates 10, 11, 15, 21 and , The Roman Military Research Society for kindly allowing the use of colour plates 16 and ; Alan Wilkins and Len Morgan for their expert advice on ballistas; the Trustees of the National Museums of Scotland for kindly allowing the use of figure ; Robin and Pat Birley and the Vindolanda Trust for generously permitting the examination of various Roman iron artefacts over the years, and for the use of colour plates 12, 13 and and figures and ; and Dr Mike Bishop for allowing the use of his collection of museum data published in the Appendix. I would also like to acknowledge the financial support for the some of the research reported here received from the Leverhulme Trust.

There are many others who have been involved in differing ways with the preparation of this book and while it has not been possible to name them all and list their kindnesses individually, their support is also gratefully recognised.

Special acknowledgement and thanks are made to the following: Dr Jamie Kaminski for his expert knowledge of the Roman charcoal industry, who has contributed the chapter on charcoal production, and additionally assisted with the preparation of the manuscript; Professor Michael Fulford for his support and guidance; and Professor Richard Chaplin for allowing the use of the facilities in the Department of Engineering.

T he inspiration for this book was the desire to produce a single volume, which covered the whole Roman-iron making process, from the first stage of finding the ore right through to the completion of the artefact. Other books have been written focusing in great detail upon some aspect or another of iron production in antiquity, and these have provided valuable sources of information. In order to keep to a manageable size, I have chosen to focus on the British iron industry, although due reference is made to the influence of the rest of the Roman empire where appropriate. Similarly, I have adopted as a theme the production of the familiar arms and armour of a Roman soldier. The basic techniques used in the production of these items will however be the same for all iron artefacts.

This book does not claim to be the final word on its topic; many aspects of the Roman iron industry are the subject of current study by experimental archaeologists, archaeologists, archeometallurgists and classicists, and new information is becoming available all the time. This study probably raises as many questions as it answers. I have highlighted the huge amount that is not known, and discuss some alternative procedures to the traditionally held views of production. It is hoped that, as well as giving information and pleasure, this book may stimulate some readers to join the group who work on this fascinating subject, and so help provide answers to the many problems that remain unsolved.

It has been difficult to strike a balance between saturating the text with references, making it unreadable in the process, and giving due credit to the many other researchers. I have aimed to be thorough and comprehensive in my acknowledgement of both early and recent work in the field, but inevitably some errors or omissions may remain. For these I accept full responsibility.

David Sim

Reading

November 2011

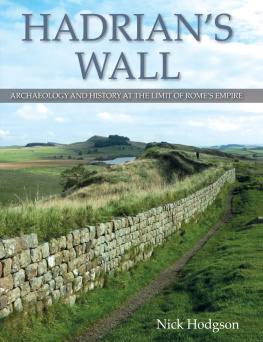

O n a warm summer afternoon in the year AD 128, just south of the great wall built by Hadrian, a Roman blacksmith is standing outside his workshop. He has just completed a full set of arms and armour, and is making a tally to check that everything he has been asked to make is accounted for. He is a legionary and a superb fighting man, but he is also proud of his skills as a blacksmith, and the sight of the equipment that he has made is a boost to his self-esteem. He has often thought that people never seem to understand either how much work goes into making things, or how important it is to be well-organised. For anything to be made, he has to make sure the iron, charcoal, tools and the other smiths are all in the same place at the same time. Nothing is left to chance; no one will ever say he forgot part of an order. On his wax tablet he marks off the following items: one helmet, one set of body armour, one shield boss, one sword, one dagger, two pila heads, one pick axe, total weight 20kg of iron. His gaze wanders over the camp and his eyes come to rest on the temple where the standard of the Legion is kept, and he remembers that day all those years ago when as a young man full of pride he swore his oath to the eagle of his Legion. His reverie is disturbed by the sight of several civilian men unloading from the mules the billets of iron he ordered. The billets are heavy, and most of the group can only manage to carry two or three at the most. One man calls out to him,

Blacksmith, whats this lot for?

And he replies: Its iron for the Eagles

In this fictional account we meet the finished product of the blacksmiths art, namely the weapons and armour that will be used by the soldiers. These items represent the end of a long story that involves large amounts of both natural resources and manpower expended to transform iron ore into the arms and armour of a Roman legionary. It is the purpose of this book to reveal the complicated and fascinating processes that have to be conducted to make such iron artefacts.

Our Roman blacksmith stands at the end of a long tradition of craftsmen, whose skills go back to the very start of mans use of metal. The first metalworkers hammered the metal to change its shape. This is the process known as forging, and copper and later bronze were fashioned in the same way. For more than a thousand years before iron was discovered, the men who forged copper and bronze were highly skilled in their art; and it was these craftsmen who were the first to forge iron, once it became available in large enough quantities. The discovery of iron, and later steel, changed everything. Steel could be made harder than any other known metal, and thus could be used to cut almost every material; even very hard stone could not resist an edge made of hard steel.

By the time of the Romans, the blacksmiths tools had reached their terminal stage of development; indeed they were in every respect almost identical to those used by blacksmiths today. Even the advent of electricity in the modern era has only meant that electric rotary fans have replaced traditional hand pumped bellows.

Quite often, iron artefacts from the archaeological record are no more than a fragile mass of corrosion products (rust), and in this condition they are neither attractive nor stimulating to those who are not enthusiasts. It is likely that this unappealing appearance has led to the importance of iron being underestimated. The lack of interest has also meant that little attention has been given to how iron artefacts came into being in the first place. Little thought has gone into considering the immense technical problems that had been overcome, and the huge amount of resources in terms of materials and man power needed to obtain a piece of iron ore (