To Sheppard Frere (19162015)

Romanist, Scholar, Academic, Historian and Archaeologist par excellence

Thank you to: Mark Hassall and Richard Reece, inspirational tutors on so many aspects of Roman archaeology at the Institute of Archaeology, University College London; Ernest Black, not only for many discussions concerning Bignor Villa over the years (especially concerning its phasing and the possible impact of historic events such as plague and civil insurrection) but also for his extensive help with this book (particularly his significant contribution to chapter 6); and to the Tupper family for their continued commitment to the care, interpretation and preservation of Bignor Villa. Without them all, Romano-British archaeology would be much the poorer.

Thank you to all the staff, students and volunteers who helped with the UCL excavations between 1985 and 2000. In particular, thanks are due to Luke Barber who supervised the 19902000 excavations.

Special thanks must go to: Lisa Tupper, for her considerable and enthusiastic help at all stages in the preparation of this particular work; Justin Russell, for producing the excellent site plans at (very) short notice; and all at The History Press, especially Cate Ludlow and Emily Locke, for their belief that, however many deadlines were missed, this book would eventually see the light of day. Thank you also to Mary, Benjamin, Bronwen, Megan and Macsen for cheerfully coping with the impact of Romano-British archaeology for so long.

This book is respectfully dedicated to Sheppard Frere whose book Britannia: A History of Roman Britain , first published in 1967, shaped so many minds and whose excavations at Bignor between 1956 and 1962 so completely changed our understanding of the villa.

C ONTENTS

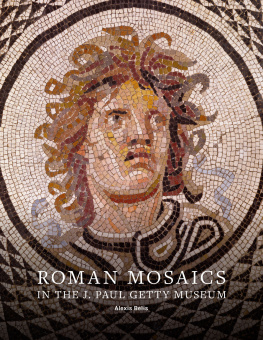

The physical manifestation of Roman cultural life, or Romanitas , in the countryside, and indeed the most well-known and popular aspect of Roman Britain today, is the villa. Some archaeologists and historians have noted their dislike of the term villa due to its connotations of luxury holiday or retirement home combined with its apparent inappropriateness when comparing British sites with those grand Roman-period villas found across Italy and the Mediterranean. The trouble is, thats just what most Roman villas appear to represent. A villa, in the context of Roman Britain, was a place where the nouveau riche spent their hard-earned (or otherwise acquired) cash. It is true that the majority of villas in Britain were at the centre of working, successful agricultural estates profits generated from the selling of farm surpluses and local industrial enterprises such as stone quarrying, pottery manufacture and forestry, presumably providing the necessary financial resources for home improvement, but lots of villas are as far away from normal working farms as one could expect.

Many villas, whether in Britain or elsewhere in the Roman Empire, possessed elaborate bathing suites, ornate dining rooms and generally had a high level of internal decor. In contrast, working farms possessed more basic, functional domestic accommodation with easy access to pigsties, cow sheds, grain stores and ploughed fields. In this respect, the earliest Roman-period villas of lowland Britain can perhaps be better compared with the grand estates, country houses and stately homes of the more recent landed gentry of England, Scotland and Wales. These houses represented monumental statements of power designed to dominate the land and impress all who passed by or who entered in. As the home of a successful landowner wishing to attain a certain level of social standing and recognition, the seventeenth-century stately home or country house was the grand, architectural centrepiece of a large agricultural estate where the owner could enhance his or her art collection, entertain guests of equal or higher standing, develop business opportunities, dispense the law and dabble in politics. In this respect the larger Romano-British villas were probably little different.

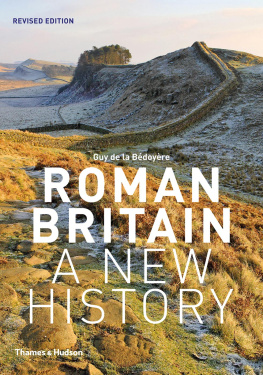

Villas are useful components in the archaeological record of Roman Britain, for they act as indicators of the relative success of the adoption of Roman culture in the province, especially in the countryside. These were not structures created by the state for ease of administration (towns), nor subjugation (forts); they were not forced upon the native population, rather they were developed by those who were, or who wanted to be, culturally Roman. They were all about show and social standing. Given that the population of Britain at this time was predominantly rural, the distribution of villas across the British Isles should provide an idea of the relative take-up of Roman fashions from the late first century AD to the collapse of central government authority in the early fifth century. Similarly, places where villas are absent might, in theory at least, be reflective of areas where the population did not desire, acquire nor even aspire to so many of the cultural attributes of Rome.

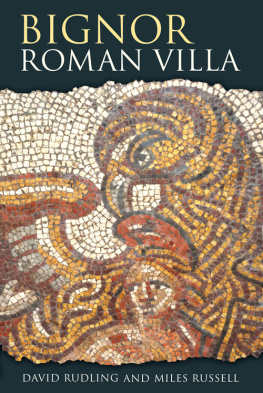

The villa of Bignor in West Sussex, southern England, is justly famous for being one of the best-preserved rural Roman-period buildings in the country. Discovered during ploughing in 1811, the villa complex was extensively explored and, for the time, well recorded with meticulous plans, isometric drawings and some artefact illustrations. Unfortunately, as was usual with early antiquarian fieldwork, these investigations were generally lacking with regard to both stratigraphic observations and the retention of all but the most interesting of finds. During this time, a series of reports on the excavations were published together with a set of detailed engravings. Although far less objective than the archaeological plans, elevations and technical drawings compiled by archaeologists today, these hand-coloured images are highly evocative, providing a wealth of information concerning the state of the villa at the time of first investigation.

Protective buildings were erected over the mosaics by George Tupper, who farmed part of the site, and by 1815 it had become a popular tourist attraction. Fortunately the Tupper Family, who now own all of the site, have never lost interest in Bignor and today it is one of the largest villas in Britain that can be visited by the public. To enter the independently thatched cover buildings and gaze down at the mosaics is an undeniably uplifting experience. The site is, of course, important, not just because of the visitor experience that it represents, but because this is one of the best understood of all Romano-British rural power houses. Whilst much of the site was exposed during the early nineteenth-century excavations, large areas were thereafter backfilled and returned to arable cultivation, and thus also exposed to further plough damage. Subsequent research at Bignor has included several episodes of re-excavation, limited investigation of new areas, geophysical survey and fieldwalking as well as an extensive re-analysis of previous discoveries.

The book before you now is an attempt to explain one of the best-preserved and certainly more famous of Romano-British villas in Britain; described by its first explorer as the finest Roman house in England. We will, therefore, take you on a journey, from the moment of first discovery on that fateful morning in July 1811, through the subsequent history of site exploration and excavation. We will then examine the remains preserved on site today and explain how our understanding of site phasing and developmental evolution has changed over the years. An opportunity will also be made to put the villa in context: who lived in it, how was it used and what did it all mean in the context of Roman Britain, before attempting to explain how in its final form this luxury residence with strong classical overtones, nestling below the grass-covered South Downs, came to an end.

Next page