Contents

Directors Foreword

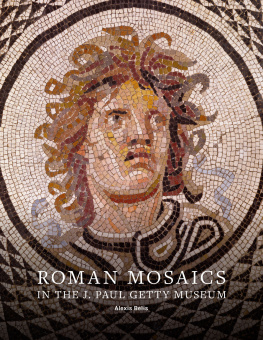

Mosaics are one of the most distinctive and widespread forms of Roman art to survive from antiquity. The majority of them covered floors and, consequently, durability was a primary reason for creating these expensive, labor-intensive compositions in colored stones and glass, imitating what could have been achieved much more easily in paint. Apart from being merely functional, floor mosaics were a significant artistic medium for the Romans. Roman Mosaics in the J. Paul Getty Museum examines several examples in the Gettys collection with detailed narrative scenes and elaborate decorative patterns that adorned reception areas and dining rooms in private villasspaces in which the owner could display his wealth, cultural sophistication, and artistic preferences. Beyond domestic settings, other significant mosaics in the exhibition embellished the interiors of a variety of public buildings, including baths, temples, and churches.

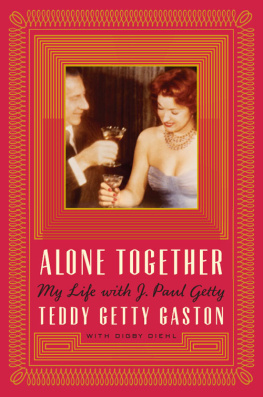

This catalogue includes all the examples of Roman mosaic art in the Gettys collection. From his earliest days of collecting antiquities in Rome in 1939, J. Paul Getty expressed an interest in this medium, commenting in his diaries on various pieces he saw in and around Rome, including those at the Musei Capitolini and the Museo Nazionale RomanoTerme di Diocleziano. He also visited the Vatican mosaic factory in Rome and, impressed by its beautiful mosaics, purchased one depicting a bowl of fruit. In his 1965 memoir, The Joys of Collecting, Getty recalls with pride how he came into possession of his first ancient mosaic, the Gallo-Roman Mosaic Floor with Orpheus and Animals (see cat. 3), in 1949. Getty was fascinated by Greek and Roman culture and, in the manner of the Romans, contracted a skilled artisan to install the mosaic over the existing floor in the Roman Room of his new museumthe Spanish Colonial ranch house in which his collection was displayed until the Getty Villa opened in 1974. Getty describes how he set one of the stones in the mosaic floor himself. Although many of the mosaics that have entered the collection over the years have been on view at the Getty Villa, some examples in this catalogue have never before been exhibited to the public or published.

Arranged geographically by regions of the Roman Empire, the catalogue entries situate each mosaic within a broad stylistic and typological framework and illuminate the context of its discovery. A number of the mosaics in the Gettys collection were included in the exhibition Roman Mosaics across the Empire, held at the Getty Villa in the spring of 2016. This publication was produced online and via print-on-demand to accompany the exhibition and make immediately available recent scholarly research on the collection. It is one of a new series of web-based catalogues of the collection of Greek, Roman, and Etruscan art at the Getty Villa. The author, contributors, and staff of Getty Publications are to be commended for realizing this innovative and accessible guide, which we hope will inspire more of our visitors to study and enjoy this important aspect of Roman art.

Acknowledgments

I extend my sincere thanks to the staff of the many departments in the J. Paul Getty Museum who were involved in the production of this catalogue, and in particular to Jeffrey Spier, senior curator of antiquities, for his support in completing this project. I am especially grateful to the other authorsChristine Kondoleon, Kenneth Lapatin, Nicole Budrovich, and Sean Leatherburywho contributed their scholarly knowledge of the mosaics in the Gettys collection, and to Judith Barr for her ongoing research on the provenance of the mosaics. I would also like to acknowledge the contributions of Andr Girod and the association of Villa Laurus en Luberon, who provided invaluable material on the archaeological site near Villelaure, where the Getty Museums mosaic of Dares and Entellus was discovered.

Special thanks are owed to the staff of the Villa Imaging Studio, especially Rebecca Truszkowski, who photographed nearly all of the mosaics for this publication, and imaging technician Benjamin Goddard, with the support of senior photographer Tahnee Cracchiola and assistant imaging technician Rosanna Chan. I extend heartfelt gratitude to Eduardo Sanchez, Jeffrey Maish, Erik Risser, Marie Svoboda, and Susan Lansing Maish in the Antiquities Conservation department, as well as conservation interns Sara Levin and Ellie Ohara, for their exceptional work in preparing the mosaics for not only photography but also display in the exhibition Roman Mosaics across the Empire. I am grateful also to Nola Butler, Greg Albers, Eric Gardner, Elizabeth Kahn, Rachel Barth, and all of the staff of Getty Publications who made this catalogue a reality.

Introduction

The mosaics in the collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum span the second through the sixth centuries AD and reflect the diversity of compositions found throughout the Roman Empire during this period. Several of the mosaics in the Getty collection can be traced to specific discoveries made in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in Italy, Gaul, North Africa, and Syria. Although the Greeks introduced the medium, using pebbles embedded in mortar, it was really the Romans, with their use of tesserae in a technique called opus tessellatum, who fully explored it as suitable ornamentation for their architecture. In fact, mosaic floors are closely aligned with Roman culture, and because of their durability they have survived in greater numbers than paintings and sculptures and testify to a lively and imaginative practice of decorative and figurative arts.

The placement of mosaics can suggest the function of the spaces they once decorated, and certain mosaic themes call on the visitor to interact with the work in a specific and intentional way. Unlike wall paintings, floor mosaics insist on movement over them and engage the viewer in a surprisingly physical experience. In order to better understand these compositions, it is critical to keep their spatial and tactile qualities in mind. Through the hundreds of visual images that survive in Roman mosaics, we can sometimes read the aspirations, anxieties, and pleasures of those who lived in the houses, towns, and cities of the Roman Empire.

The Roman architect Vitruvius, in his treatise on architecture, De Architectura, documents the techniques used for the preparation of mosaic pavements, but he does not indicate how the tesserae were gathered or cut, or how the compositions were laid out. The use of mosaic pavements followed the spread of Roman culture throughout the empire during the Imperial period (about the first through fourth centuries AD). When painterly effects were desired, the colored stones were cut into very small tesserae, and sometimes glass was used to create tones of orange, yellow, blue, and green not easily found in nature. In view of the grand pictorial works such as the Alexander Mosaic from Pompeii and the number of similar examples found throughout the empire, it is reasonable to assume that mosaicists, like painters and weavers, relied on cartoons, drawings, and sketchbooks. However, the artisans were highly skilled and clearly at liberty to be flexible and imaginative with their commissions, so no one mosaic is exactly like another.

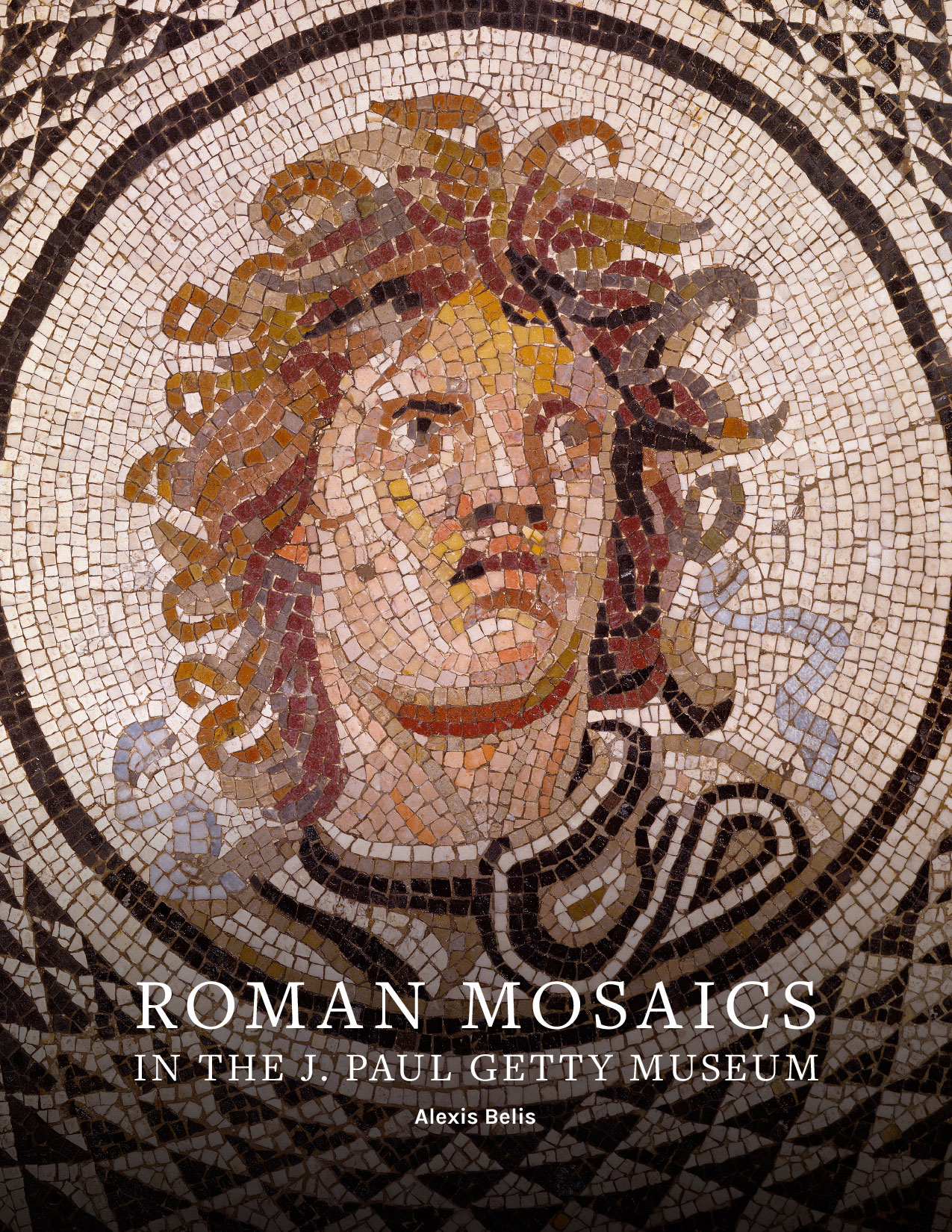

As the empire expanded, the elite increasingly displayed their wealth and Roman identity in private settings. Regional workshops developed to meet the increasing demand for domestic mosaics. The mosaics in the Gettys collection reveal a rich variety of approaches from different parts of the Roman Empire. Certain themes and organizational patterns were typical of particular regions. In Italy, for example, black-and-white style mosaics came into fashion in the late Republic (mid-second to first century BC) and remained popular well into the third century AD. The Getty Medusa (), most likely of the Hadrianic period (during the reign of the emperor Hadrian from AD 117 to 138), is largely black and white with a polychrome center featuring a frightening serpentine visage. Triangles of black and white produce a swirling circular pattern around the Gorgons head, directing the focus to the central image, which in this case was probably also the center of the room. The fact that almost all the extant Medusa mosaicsabout one hundredare set within a kaleidoscopic pattern that produces the impression of motion suggests that the ancients believed the kinesthetic effect of ornament could work in tandem with the mythic image of the Gorgon to ward off evil.