THE HOUSE OF GETTY

Russell Miller

Contents

Prologue

The Midas contagion

In the grounds of a white-painted hacienda overlooking the Pacific at Santa Monica there is a simple marble mausoleum, forlornly unvisited. Three names, companionable in death as never in life, are engraved on the facade: J. Paul Getty 1892-1976, George F. Getty II 1924-1973, Timothy Getty 1946-1958.

Paul Getty, once said to be the richest man in the world, last saw this place more than thirty-five years ago, when it was a tranquil oasis of lawns, eucalyptus trees and lemon groves, tucked into the lower flanks of the Santa Monica mountains. Today, traffic roars day and night along a nearby six-lane highway lined with gimcrack motels and junk-food joints. Where the mountains were once covered with chaparral, they are now covered with condominiums. Where there was once the sweet smell of the ocean, there is now the noxious stench of exhaust fumes, hamburgers and pizzas.

Even in death, the Gettys can find no peace.

The old man shares the mausoleum with the oldest and youngest of his five sons. First to die was little Timmy who, like his famous namesake Tiny Tim, was marked out from the start by the angelic nature even saintliness that so often characterises the chronically sick child. His father adored him, but saw him infrequently, since Timmy lived in New York and Getty lived in hotel suites in Europe. A few weeks before Timmy was twelve, Getty telephoned to ask the boy what he would like for his birthday. He replied: I want your love, Daddy, and I want to see you. He died in hospital a few weeks later, without seeing his father. Getty was devastated.

But there was still George, big, bluff George the only Getty of his generation to show any interest in the family business. To their fathers despair, Ronnie, Paul and Gordon were all hopeless businessmen and, one by one, they dropped out of Getty Oil. It was George who was groomed to take over, George who would ensure that a Getty remained at the helm of the business founded by his grandfather and built into an empire by his father. Then George killed himself.

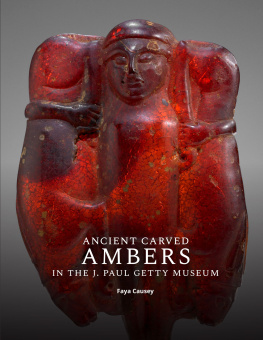

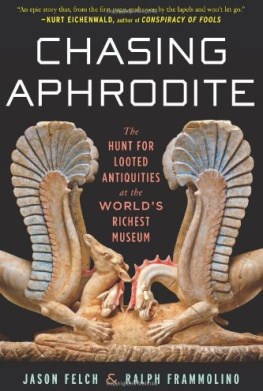

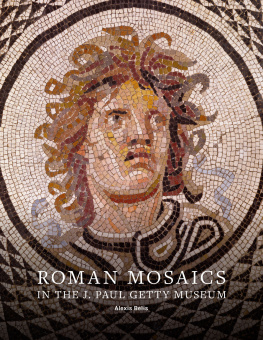

With his cherished hopes of a dynasty crushed, the old man looked to his museum for a lasting memorial, a monument to his success, and he made it into the most richly endowed foundation in the world. But money tainted his philanthropy, just as surely as it rotted the enigmatic bonds that normally bind families together. The J. Paul Getty Museum became feared for its fabulous wealth and the threat it represented to the stability of the art market. Its power became universally known as the Getty factor. Instead of a monument, the old man begat an epithet.

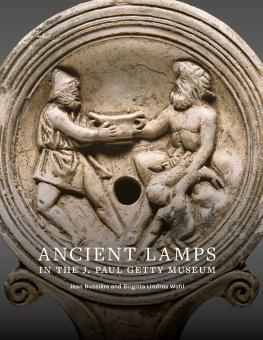

The museum is not far from its creators last resting place, just a short walk along a gravel path which winds through thickets of lustrous evergreen shrubs. It is a rich mans folly, just as ludicrous and wonderful as San Simeon: a full-scale replica, here in Malibu, California, of a Roman villa which was buried by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD. Getty never saw it, but was hurt when critics derided it as being like something out of Cecil B. De Mille.

The eldest of the old mans three surviving sons, Ronald, lives close by the museum. Just outside the gates, turn left along the Pacific Coast Highway, left again into Sunset Boulevard, then left through the wrought iron portals of Bel Air. Some of the most high-profile personalities in the world live here. Ronald Getty is not one of them. He is a failed film producer and sometime real-estate developer, a large, surly man with the appearance and demeanour of a dour bank manager, who is rarely seen in public except when he is required to make an appearance in court.

The Gettys are ferocious litigants. In the chaotic records office at Los Angeles Superior Court, entire shelves are occupied by volume after volume of yellowing documents chronicling the Getty family squabbles. Most of the time, the Gettys fight about money divided by the very stuff that was to have proved their making although Ronalds mother once filed a suit to evict her son from his house on South Beverly Glen Boulevard so that she could live there alone. Ronald professed himself to be distressed that she had chosen to air family problems in public nevertheless, when the time came, he did not shrink from nursing his own vendettas through legal channels too.

A recent long-running courtroom drama centred around payments made by a family trust to J. Paul Gettys heirs. Ronald was aggrieved, for some reason, that he received only $3000 a year from the trust, whereas his half-brothers, Paul and Gordon, did rather better, collecting around $120 million a year each. His attempts, through the courts, to obtain an equal share of the family fortune were naturally vigorously opposed by his loving brothers, who took the view that Ronalds miserly share was Ronalds bad luck. Actually, the explanation is rooted in the murky past. Fifty years ago Getty, angered by the amount he had to pay to divorce Ronalds mother, took his revenge by virtually disinheriting their son a wholly arbitrary act that effectively ensured the present feud between Ronald and his brothers.

But Ronalds suit was no more than a passing tiff when compared to the fury recently directed at the cherubic head of Gordon Getty, who was sole trustee of the $4-billion family fortune and was named in 1984 as the richest man in America. Gordon, an enthusiastic amateur composer and singer, affects the distracted mien of an absent-minded, slightly dotty, but thoroughly endearing professor. He is liable to wear odd socks, for example, or forget where he has left his car, or close his eyes during a dinner party to study opera scores. Tall and curly-haired, he lives with his wife Ann and four sons in a three-storey mansion in San Francisco with a wonderful view across the bay to the Golden Gate bridge. For a multi-millionaire, his lifestyle is unostentatious : he likes camping with his kids and watching football on television, particularly if his home-town team, the San Francisco 49-ers, is playing.

Being of a musical and artistic bent, Gordon was perhaps doubly unwelcome when he began to take an interest in Getty Oil, to the exasperation of the directors who viewed him as something of an eccentric. Irritation turned to alarm when Gordon became enamoured of the idea of following in his fathers footsteps as an oil tycoon and taking over control of the company. I didnt want to go into the office every day, he said, but I would like to have been able to call the shots.

He was never to get the chance, though. If the company directors were alarmed, his relatives were outraged at the prospect of dreamy Gordon running Getty Oil and rushed to their lawyers. Gordon was positively deluged with lawsuits: even his fifteen-year-old nephew, the exotically named Tara Gabriel Galaxy Gramaphone Getty, issued a writ. Most of the suits were aimed at clipping Gordons wings by getting a co-trustee appointed, but George Gettys three daughters (known in the family, unaffectionately, as the Georgettes) filed a suit to have Gordon declared unsuitable as a trustee and thrown out.

When it dawned on Gordon that he was not going to be able to take over the reins of Getty Oil, he declared his second preference was to sell the company. This naturally prompted further writs, but he was not to be thwarted: out of the mele there emerged the biggest corporate takeover in US history a $9.9 billion dollar deal to sell the family business to Texaco. Afterwards, one of the Georgettes fired off a bitter and angry letter to Gordon. I hope you are satisfied, she wrote, now that Getty Oil is gone.