CONTENTS

C IVILISATION is a matter of perspective. Nowhere is this more clear than when comparing the literary or artistic output of particular cultures, for such works represent a discrete point of view; the defining statements of distinct ethnic groups; perspectives written about a particular society by members of that society in order to educate, satirise, entertain or inform. When examined at a very basic level, most literary works appear to be driven by three basic imperatives: where shall I live?, who will I marry? and what are we having for lunch? If you take two particular, and perhaps rather exaggerated, literary masterpieces detailing the eating habits of Mediterranean Rome and Celtic north-western Europe, then the differences cannot seem more extreme.

The Story of Mac Daths Pig, one of the most famous Irish sagas, belongs to the so-called cycle of Ulster, an epic first set down in the eleventh or twelfth century AD , but it ultimately describes (and derives from) a much earlier pre-Christian world. The story of the pig covers, as its main theme, the events surrounding a feast set within the great hall of Mac Dath, king of Leinster.

There were seven doors in that hall, and seven passages through it, and seven hearths in it, and seven cauldrons, and an ox and a salted pig in each cauldron, the anonymous author tells us. Every man who came along the passage used to thrust the flesh-fork into a cauldron, and whatever he brought out at the first catch was his portion. If he did not obtain anything at the first attempt he did not have another. Having set the scene, the narrator then describes the carving of a great, spit-roasted pig and the challenges over who was entitled to the hind leg, or Champions Portion.

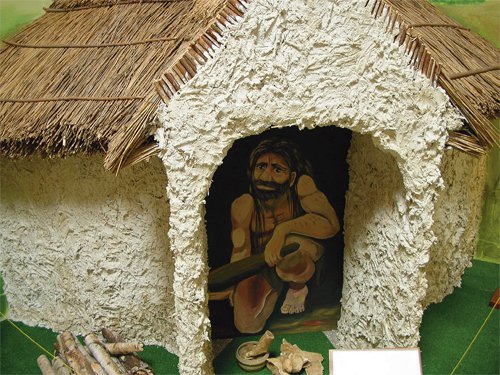

1 UnRoman. A distinctly aggressive-looking pre-Roman roundhouse inhabitant in the Ringwood Town and Country Museum, Hampshire

It shall not be, said a tall fair hero who had risen from his place, that Cet should divide the pig before our faces. Whom have we here? asked Cet. He is a better hero than you are, said everyone; for he is Angus mac Lam Gbuid of Ulster. Why is your father called Lam Gbuid? asked Cet. We do not know indeed said all. I know, said Cet. I once went eastward. The alarm was raised against me. Everyone came on and Lam came too. He threw a cast of his great spear at me. I sent the same spear back to him, and it struck off his hand, so that it lay on the ground. What could bring his son to give me combat? Angus sat down. Keep up the contest further said Cet, or else let me divide the pig. It is intolerable that you should take precedence in dividing the pig said a tall fair hero of Ulster. Whom have we here? asked Cet. That is Eogan mac Durthacht said everyone. I have seen him before, said Cet. Where have you seen me? asked Eogan. At the door of your house, when I deprived you of a drove of cattle. The alarm was raised around me in the country-side. You came at that cry. You cast a spear at me so that it stuck out of my shield. I cast the spear back at you so that it pierced your head and put out your eye. It is patent to the men of Ireland that you are one-eyed. It was I who struck out the other eye from your head. Thereupon the other sat down.

In contrast to Mac Daths Pig, is the Satyricon, an incomplete Latin work of fiction detailing the (mis)adventures of one Encolpius. This is about as far away from the smoking hearths and roasted pigs of Ireland as one could imagine. It was written in the mid first century AD by Petronius, possibly the same Petronius known to history as a fashion advisor, pleasure-seeker and general judge of elegance in the court of the emperor Nero. One of the more famous surviving sections of the work describes a banquet hosted by Trimalchio, a freedman of enormous wealth, but ultimately little taste.

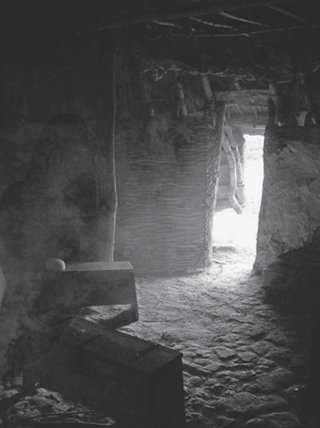

2 UnRoman interior design: inside the reconstructed roundhouse at the Cranborne Ancient Technology Centre, Dorset

All were now at table except Trimalchio, for whom the first place was reserved Among the hors doeuvres stood a little ass of Corinthian bronze with a packsaddle holding olives, white olives on one side, black on the other. The animal was flanked right and left by silver dishes, on the rim of which Trimalchios name was engraved and the weight. On arches built up in the form of miniature bridges were dormice seasoned with honey and poppy-seed. There were sausages, too, smoking hot on a silver grill, and underneath, Syrian plums and pomegranate seeds We were in the midst of these delights when Trimalchio was brought in with a burst of music. They laid him down on some little cushions, very carefully Then going through his teeth with a silver pick, My friends said he, I really didnt want to come to dinner so soon, but I was afraid my absence would cause too great a delay, so I denied myself the pleasure I was at, at any rate I hope youll let me finish my game. A slave followed, carrying a checkerboard of turpentine wood, with crystal dice and with gold and silver coins instead of the ordinary black and white pieces. While he was cursing like a trooper over the game and we were starting on the lighter dishes, a basket was brought in on a tray, with a wooden hen in it, her wings spread round, as if she were hatching At once the orchestra struck up the music, as the slaves also struck up theirs In the bustle a dish chanced to fall, and when a boy stooped to pick it up, Trimalchio gave him a few vigorous cuffs for his pains, and bade him to Throw it down again and a slave coming in swept out the silver platter along with the refuse. After that two long-haired Ethiopians entered with little bladders, similar to those used in sprinkling the arena in the amphitheatre, but instead of water they poured wine on our hands. Then glass wine jars were brought in, carefully sealed and a ticket on the neck of each, reading thus: Opimian Falernia, One hundred years old.

The contrast between the heroic and violent machismo associated with mealtime in Celtic Ireland and the effete decadence of a Roman dinner party cannot be more striking. But then thats the point. These two texts were chosen deliberately and, if and when cited in works of modern history, are noted without comment as if they were objective statements concerning the reality of ancient life. The Romans were debauched, the Celts aggressively quarrelsome. Of course, thats not the whole story, for selection of alternative texts could have emphasised the dark, violent underbelly of Roman life or the decadent exuberance of the barbarian Celt. The important thing to note here is that both the works cited above were created within well-developed artistic cultures. They are both introspective and, arguably, hugely satirical. They also demonstrate, in very different ways, the great literary heritage of Rome and the Barbarian.

Civilisation, as we said, is a matter of perspective.

T HE N ATURE OF C HANGE

In most considerations of Rome in Britain, opinion is divided as to whether the Roman Empire was or was not a good thing. The situation facing the indigenous population of first-century AD Britain is often depicted as if it were clear cut: you were either with Rome or against her. If you sided with the Romans you were either forward thinking, a visionary hoping to participate in a great social experiment and benefit from all the things that a Mediterranean-based civilisation could offer, or a quisling, a collaborator, a turncoat betraying your own people. If you took a stand against Rome, you were either a courageous freedom fighter trying to liberate your friends and family, or a squalid terrorist, living life on the run and in constant fear of arrest.

Next page