Pagebreaks of the print version

The Long War for Britannia, 367664

The Long War for Britannia, 367664

Arthur and the History of Post-Roman Britain

Edwin Pace

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by

Pen & Sword Military

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright Edwin Pace 2021

Extract from Anglo-Saxon Chronicle copyright 1990

by G.N. Garmonsway reprinted by permission of

The Orion Publishing Group, London

Extract from Nennius copyright 1980 by John Morris and

Gildas copyright 1978 by David Winterbottom reprinted

by permission of Phillimore Book Publishing, West Sussex

ISBN 978 1 39901 375 8

eISBN 978 1 39901 376 5

mobi ISBN 978 1 39901 376 5

The right of Edwin Pace to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Croydon, CR0 4YY.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail: Uspen-and

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

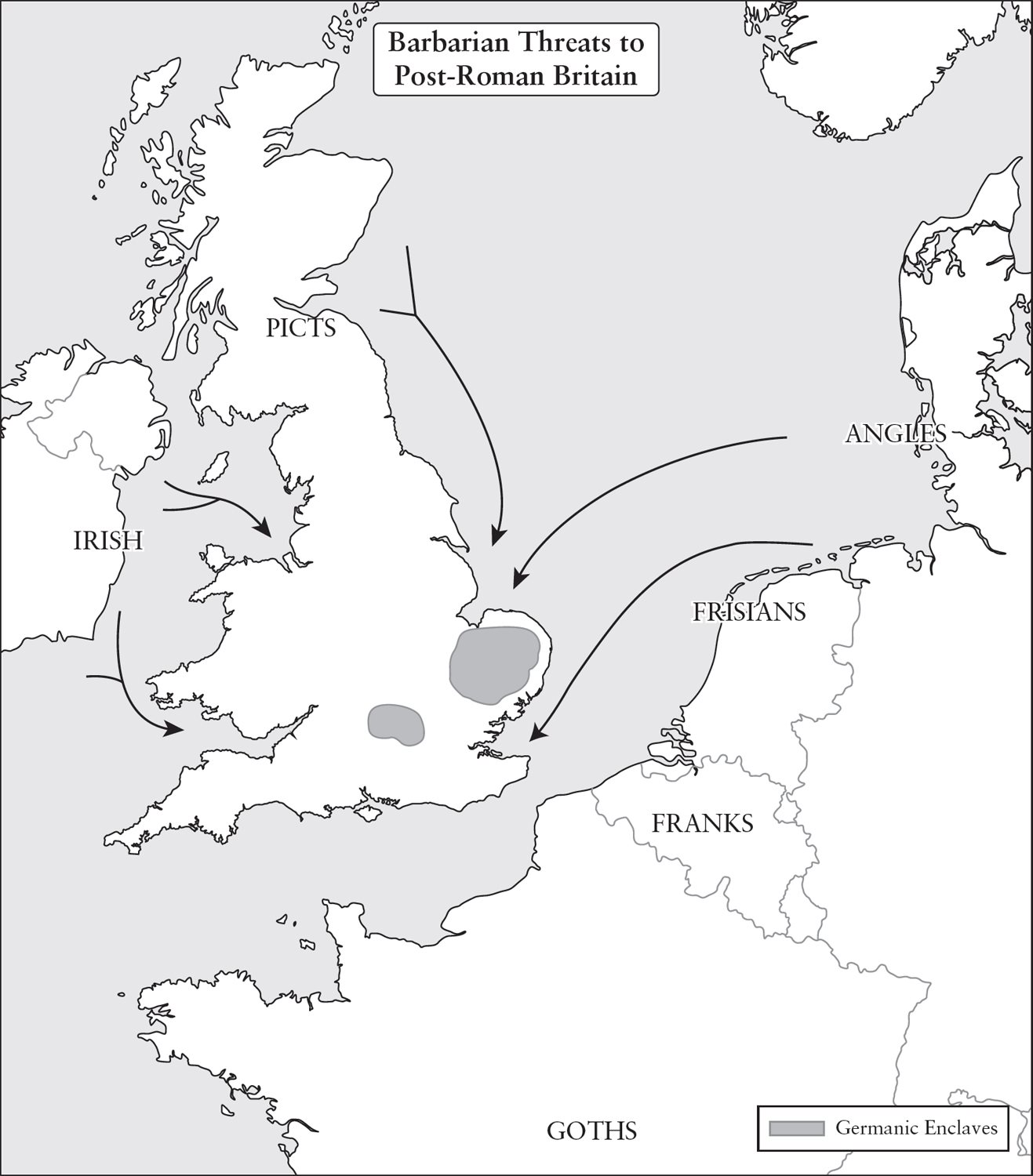

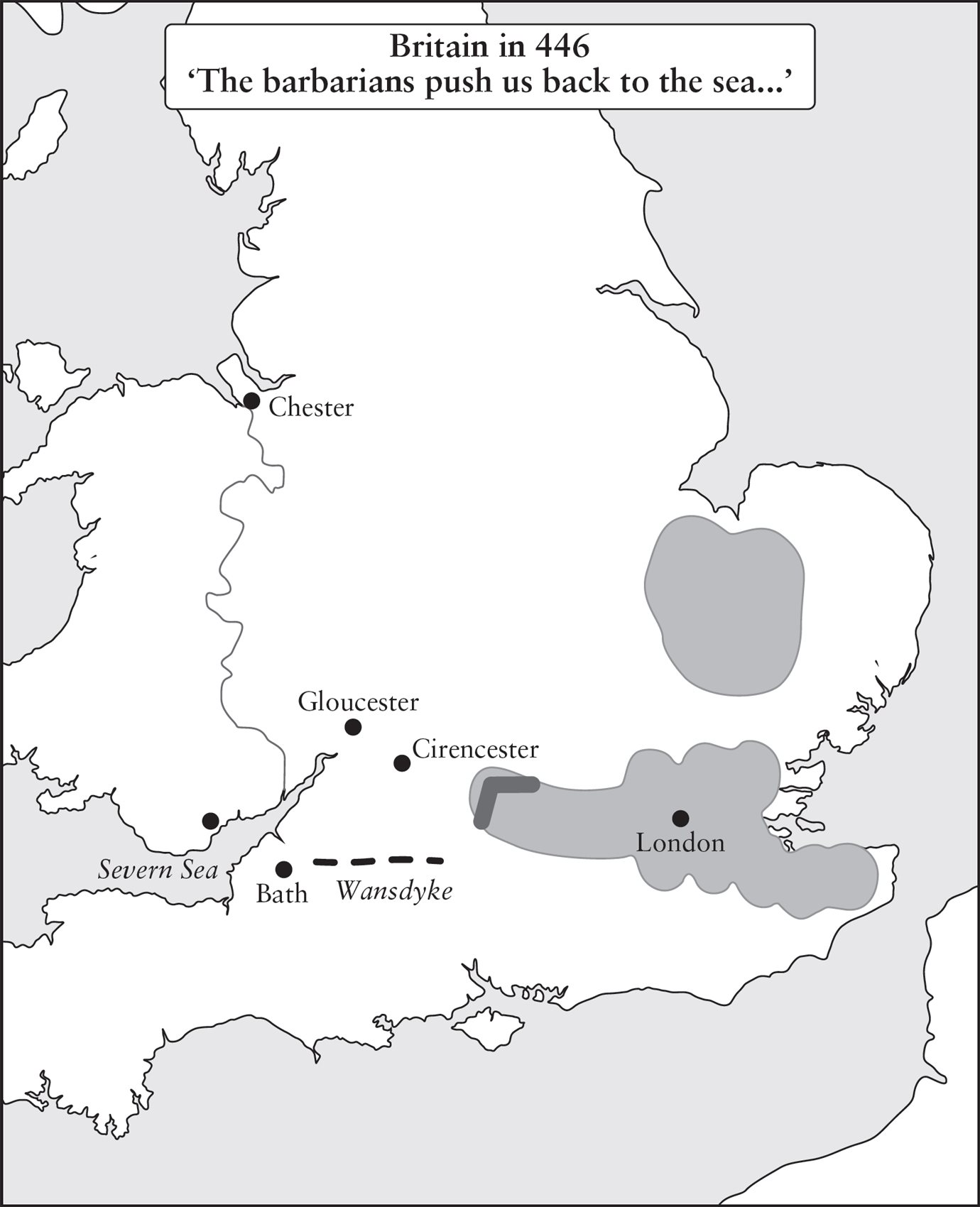

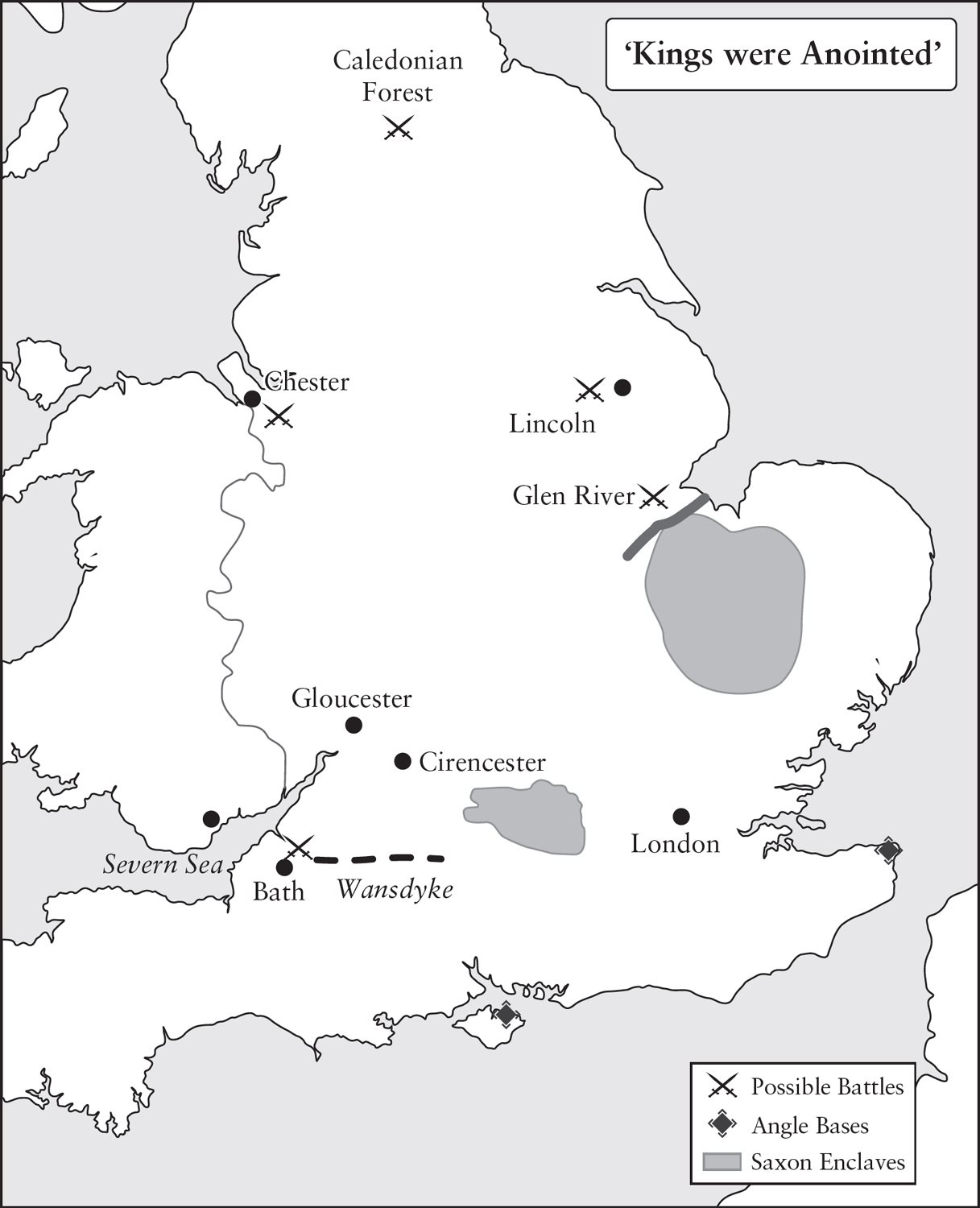

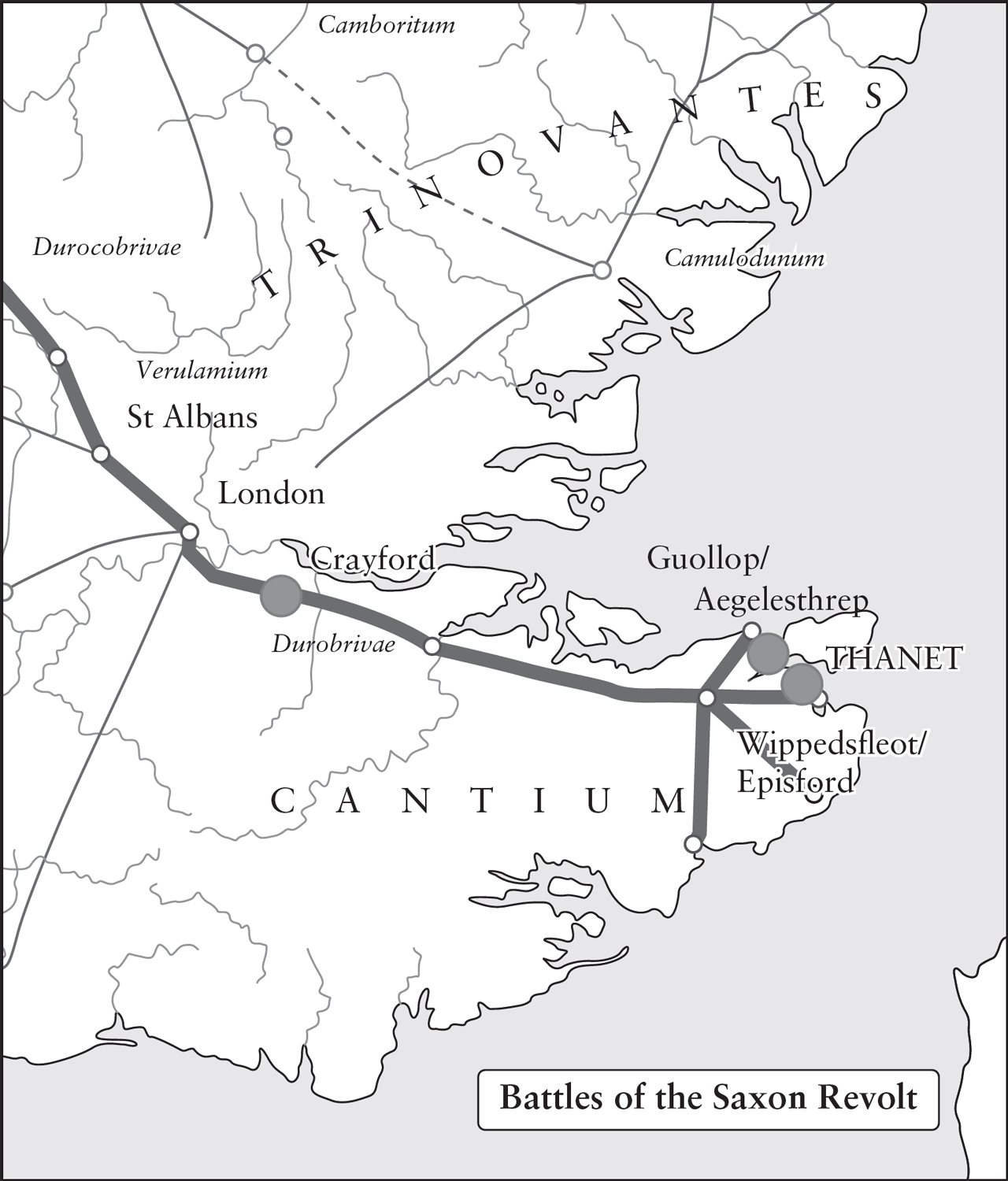

Maps

Fake News and King Gormand

T his book tells the story of a radical transformation. In the fourth century AD , Britanniae was an integral part of the Roman Empire. Latin was spoken in every corner of the diocese, Romes army stood watch on Britanniae s borders and goods flowed in from the far ends of the empire. But by the seventh century, the Romans were gone and almost every aspect of life had changed. Roman buildings were in ruins, while the island was divided into a dozen petty kingdoms. Latin disappeared as a living language, replaced by early forms of Welsh, English and Irish. The outlines of the modern states of Wales, England and Scotland were already apparent.

The written records for this story are scanty. More to the point, they provide a picture of this period that few historians now accept. We will call these early narratives the historiography of the island of Britain. Many scholars dismiss them as fake news, the most notorious of these alleged fakes being Geoffrey of Monmouths The History of the Kings of Britain .

One example illustrates the problem and points to a way forward. This is Geoffreys story of Gormand the African. Sometime after the death of King Arthur, Geoffrey claims that an African ruler called Gormand led an army of 120,000 Africans to the island of Britain. Strangely, however, these supposed Africans sailed in from Ireland. They then occupied Cirencester. After a year, they are said to have fanned out across Britain, plundering both Briton and Saxon. Geoffrey claims that it was Gormands Africans who destroyed what remained of Arthurs kingdom.

We have every right to reject this narrative as pure fiction. Indeed, one well-regarded scholar has argued that it all comes from just three words in the earliest historical work for the period. Geoffrey is supposed to have playfully expanded it into the vivid narrative now found in his History . This seems a reasonable conjecture: while we have no direct proof that Geoffrey created a complex narrative out of just three words, what other explanation is there? In current academic parlance, the doubt about Gormand is a valid discourse.

Or is it? If we actually examine the evidence, a very different picture emerges:

The ninth-century Viking Great Army, under its leader Guthrum, did indeed devastate large parts of England and Wales;

many of these Vikings came from Ireland, just as Gormand did;

all but one of the seven English kingdoms succumbed to the invaders;

Guthrum occupied Cirencester for a year;

English, Irish and Welsh sources from the ninth century call Guthrums Vikings black pagans, easily misunderstood as Gormands Africans;

finally, the ninth-century English name for Guthrum was Gurmund.

In other words, every element of the Gormand story is consistent with genuine records from ninth-century Britain. Geoffreys source has gravely misunderstood the context of the story; Gormand has been placed in the wrong era and much of the evidence is distorted. But Gormand is not a tall tale. It is not fake news. In fact, it is not even new. In 1895, the German scholar Rudolf Zenker gave the most plausible identity for Gormand, noting William of Malmesburys testimony that the English name for the Viking leader Guthrum was Gurmund. He reported how what are termed Insular sources often called Danish Vikings black pagans. But scholars were so fixated upon Geoffreys supposed duplicity that Zenkers testimony was ignored.

This emphasizes something more fundamental: that a narrative can be entirely authentic, but when placed in the wrong context it ceases to be historical. This is particularly true with regard to chronology. If Waterloo and Gettysburg were both misdated to 1840, we would have false impressions of both the Napoleonic Wars and the American Civil War. Since they would inevitably contradict other evidence for this period, scholars might even argue that the two conflicts never occurred.