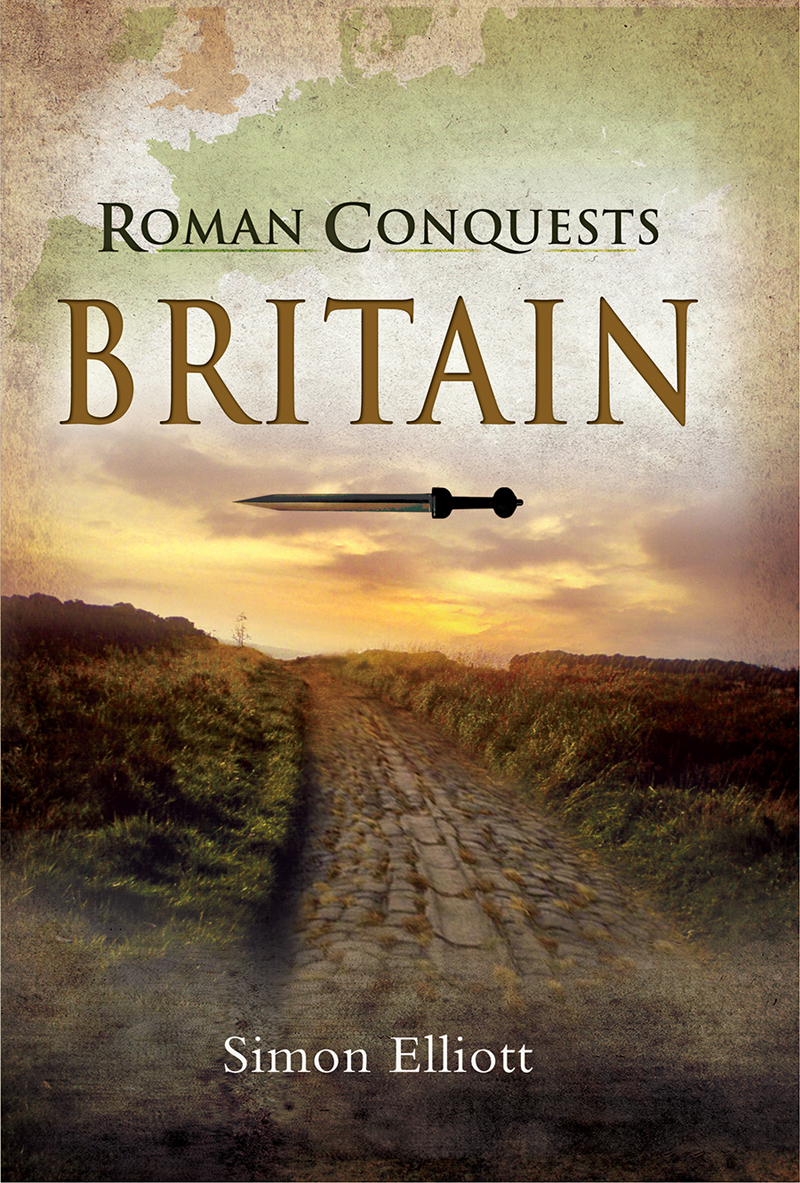

Roman Conquests: Britain

Roman Conquests: Britain

Simon Elliott

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by

Pen & Sword Military

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

YorkshirePhiladelphia

Copyright Simon Elliott 2021

ISBN 978 1 52676 5 680

eISBN 978 1 52676 5 697

Mobi ISBN 978 1 52676 5 703

The right of Simon Elliott to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

List of Tables

Table 1: The Legions of the Roman Principate

Table 2: Known Auxiliary Cohorts and Alae of the mid-late 2nd century AD

Table 3: Regional Fleets of the Roman Principate

By the same author:

Sea Eagles of Empire

Empire State: How the Roman Military Built an Empire

Septimius Severus in Scotland

Roman Legionaries

Ragstone to Riches

Julius Caesar: Romes Greatest Warlord

Old Testament Warriors

Pertinax: The Son of a Slave Who Became Roman Emperor

Romans at War

Roman Britains Missing Legion: What Really Happened to IX Hispana?

Denotes titles in print with Pen & Sword Books/Greenhill Books

Introduction

O f all the conquests made by the Roman Republic and Empire, Britain was the least successful, specifically because of the way the territory was conquered (or not in the case of the far north and Ireland). This meant it required an exceptionally large military presence that, twinned with its distance from Rome, later made it a hotbed for usurping would-be emperors. To the Romans, Britannia truly was the wild west of the Empire. This sense of difference was then firmly cemented in place by the shattering way Britain left the Roman Empire in the early 5 th century AD, an event so dramatic that it still resonates in the world we live in today.

Britain provides one of the starkest examples of the legacy of the Roman Empire. Today many believe it is a place of difference in Western Europe when compared to its continental neighbours. However, few realise this perceived sense of variance dates back directly to the period of Roman rule. Before the arrival of Rome in northwestern Europe, many British tribes had strong political, economic and cultural links with continental Gaul, to the extent that some actually shared the same name. Not so once Caesar had conquered Gaul in the 50s BC, cutting Britains La Tne cultural umbilical with the continent. The later creation of the province of Britannia by Claudius in AD 43 should have rectified this, integrating Britain into the Roman Empire. However, to a large extent it didnt.

The way that Britain was conquered by the Roman Empire also left very specific legacies in the British landscape today. This was again because of the way the campaigns here were fought. Caesar conquered Gaul in a comparatively short eight years, with the territory there quickly incorporated into Republican Roman provincial territory. A key reason regarding the speed of the latter was the sheer scale of slaughter and destruction as Caesar scoured Gaul again and again, often returning to conquered territories to stamp out rebellion.

However, the story of conquest in Britain was very different. It was a difficult place to invade in the first place, a terrifying land of which the Romans knew little, across fearsome Oceanus as the Romans called the northern seas. Caesar himself failed (if his intention was to stay, this is unlikely) in 55 BC and 54 BC, and the great Augustus and mad Caligula both planned but abandoned conquest. Even the Aulus Plautius-led invasion of Claudius was problematic. Here, the troops were again wary of making the crossing until shamed into boarding the invasion fleet by one of the emperors senior freedmen. Though this invasion was successful, and the new province of Britannia created, from that point progress to expand Imperial territory was often slow, painful and bloody, ultimately taking 60 years before the highpoint of Gnaeus Julius Agricolas campaigns in the far north. This was the only time the Romans could claim to have conquered the whole main island of Britain, and then very briefly if they did so.

Meanwhile, because of the need to physically lock down newly occupied areas with fortifications large and small, the legacy of Roman conquest here is physically written across the landscape. Many of todays leading cities and towns in England and Wales were originally Roman legionary fortresses or vexillation forts, and their canabae or vicus civilian settlements. Meanwhile, to service the campaigns of conquest and then maintain order, the province was threaded with a well-built system of military trunk roads. Today these remain the template for much of Britains pre-motorway A-road network.

A further legacy in Britain of the Roman campaigns of conquest is the modern political settlement of the islands here. Firstly, the Romans never invaded Ireland, though Agricola briefly considered it. Therefore it never became part of the Roman Imperial project and has remained a separate political entity to this day. Secondly, despite Agricolas best efforts and those of Septimius Severus (see below), the Romans never permanently conquered the far north, it too remaining a separate political entity (or entities), today in the form of modern Scotland. As to why the whole archipelago was never fully conquered, James (2011, 144) makes the case that this was the result of a failure of the open hand alongside sword strategy that had underwritten much of Romes early Imperial growth. He says this required an elite sophisticated enough in newly conquered territories to buy into the Imperial project once conquest had taken place. He adds such an elite was singularly lacking in what is now Ireland and Scotland until later in the occupation of Britain, by which time the Romans didnt have the political will or means to carry out campaigns of conquest there.

Most people associate the Roman campaigns of conquest in Britain with those of Caesar, Claudius, and the warrior governors of the mid- and later 1 st century AD. However, there were many others. For example, for a short time in the mid-2 nd century AD the northern border was driven northwards from the line of Hadrians Wall to a new frontier along the Clyde-Forth line, today called the Antonine Wall. Then, in the early 3 rd century AD, Septimius Severus launched his two enormous campaigns to conquer the far north, gathering the largest ever military force to campaign in Britain. Later in the same century Constantius Chlorus mounted the fourth and final Roman maritime invasion of Britain to defeat the North Sea Empire established by the usurper Carausius. Even in the 4 th century AD, as we near the end of the Roman occupation, we have intense military campaigning in Britain as the likes of Comes Theodosius and Stilicho (even if not in person) strove to defeat multiple threats from Ireland, the far north and modern Germany. All are considered here.

Next page