To Esther (again)

You remain

My power, my pleasure, my pain

First published in Great Britain in 2010 by

Pen & Sword Military

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Nic Fields, 2010

ISBN 9781844159703

Digital Edition ISBN 9781848847040

The right of Nic Fields to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in 10 on 12pt Times New Roman by Acredula

Printed and bound in England By CPI

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation,

Pen & Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military,

Wharncliffe Local History, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics,

Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Acknowledgements

When our thoughts turn to Carthage we automatically think of suicidal Dido and her fatal love affair, and, of course, the unlucky Hannibal and his elephants. Didos relationship with Aeneas is one of the best-known love stories of all time and countless writers, poets, painters and composers have been inspired by it. Similarly, Hannibals passage of the Alps, along with the charge of the Light Brigade and Custers last stand, has stirred the imagination of humankind. They were, however, only two dramatic details on a much larger canvas of historical (mythical) events. And for that discovery, I am forever indebted to John Lazenby and his stimulating teaching.

I offer my sincere thanks to Philip Sidnell of Pen & Sword Books for his Herculean patience with my extreme (glacial, in truth) slowness and philosophical peculiarities. I am grateful, as well, to Elizabeth James for her careful and helpful reading and for her understanding of the finer points of the Latin language. I should like to offer a big thank you to Graham Sumner and Ian Hughes; the first for his artwork, the second for his mapwork. This volume is far richer as a result of their artistic talents and labours. Finally, trite though it may seem, my greatest thanks (as ever) go to Esther, who, once again, has been with me on this project all along the (rocky) way.

Maps

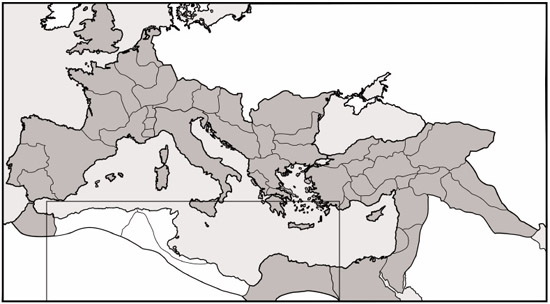

L IST OF M APS

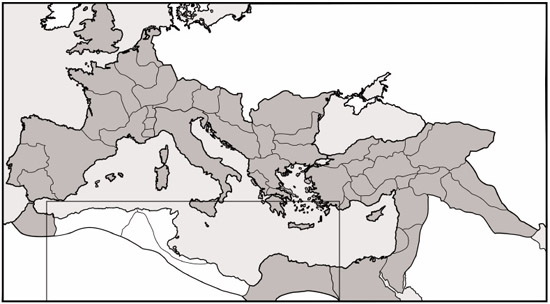

The Roman Empire at its greatest extent, with the area covered in this volume highlighted.

List of Illustrations

Prologue

R OME AND THE REST

Let us begin our story with an amusing anecdote. As the armies were deploying to commit themselves to the lottery of battle, it is commonly said that Antiochos of Syria turned to Hannibal Barca, the luckless but bewitching Carthaginian general who accompanied his entourage, to enquire whether his army, its ranks gleaming with silver and gold, its commanders grandly arrayed in their heavy jewels and rich silks, would be enough for the Romans. Indeed they will be more than enough, sneered Hannibal, even though the Romans are the greediest nation on earth.

If we were lucky enough to be able to ask the citizens of ancient Rome how they saw their empire, then almost certainly the view of the Augustan poet Virgil would probably cover the vast majority of current feeling: an empire with no limits. We, in our post-Cold War world, readily deplore the craving of conquest and the cruelty of conquerors. Imperialism, that ageless human concept of acquisitiveness, implies a conscious desire to take and possess, and if it is to carry weight in the historical balance, it must lead to some spectacular and abiding achievement. As westerners we tend to associate, by tradition, Rome with the superior aspects of Latin culture, namely the legacy still with us today in law, administration and language, while those of us who live in Europe, the Levant or North Africa have the added bonus of being surrounded by concrete reminders of its former grandeur. The Roman Empire at its zenith, and at its most confident (roughly, 27 BC to AD 235), covered vast tracts of three continents, Europe, Africa and Asia, encompassed countless cultures, languages and climates, and included nomads and farmers, tribesmen and urbanites, brigands and philosophers. Rome was anticipatory of a world composed of the most diverse elements and people, and its empire would be synonymous with that world at peace.

The idiomatic expression pax romana was borrowed from the elder Pliny, the learned Roman admiral who perished during the terrible eruption of Mount Vesuvius in the year AD 79. When he penned it, he was reflecting upon the flora now available to the botanist from all the corners of the world, thanks to the boundless majesty of Roman peace. In Plinys time, peach and apricot trees had just arrived in Italy, the former probably originating from China and the latter from the land we know now as Turkestan. Walnut and almond trees from the east had only recently arrived, as had the quince bush from Crete. Naturally all this talk of seeds, cuttings and grafts ignores the fact that empire had to be bought with the coin of human degradation: murder, brutality, starvation, dispossession.

Repugnant though this is, the pax romana is not to be sniffed at, more so if we consider the terrible plight of our own world today, where universal peace appears to remain a mere will o the wisp. Conflict is as much a part of the contemporary world as ever, and we are all, either through actual experience or through mediated experience, the children of war. Though certainly not as happy and prosperous as the supposed golden age of Edward Gibbon, the population of the Roman Empire, despite notable exceptions, was at least to enjoy relative quiet for two-and-a-half centuries. This was something new, as yet to be repeated, to the human condition. Even so, there is something else. Empires are not acquired in a fit of absence of mind, but through a conscious policy of expansion.

In its broad outline, the manifest destiny of Rome was devastatingly simple. The mood of the time, if correctly reflected in the literature of the day, leans unmistakably toward irresistible expansion beyond the confines of the Italian peninsula on the grounds of mission, decreed fortune, and divine will. Romes greatest orator, Cicero, gave it an air of the miraculous when he blustered that Romulus had from the outset the divine inspiration to make his city the seat of a mighty empire.

Next page