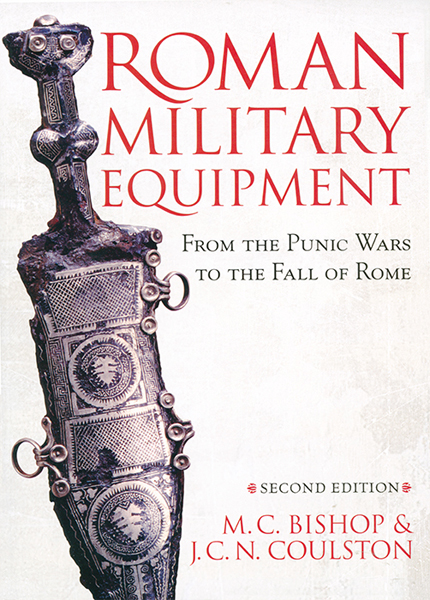

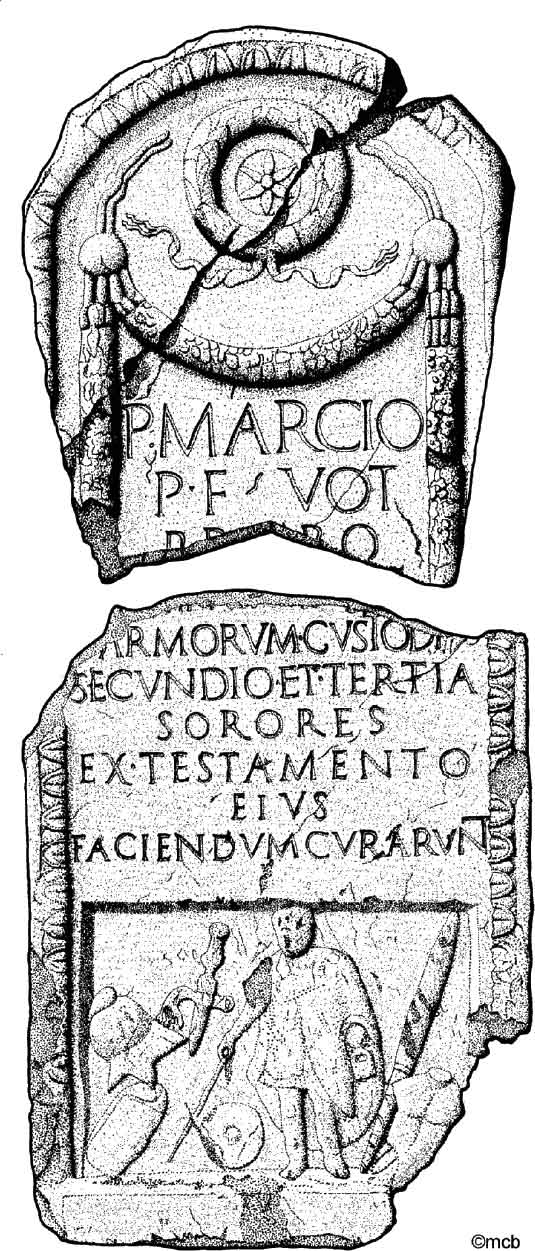

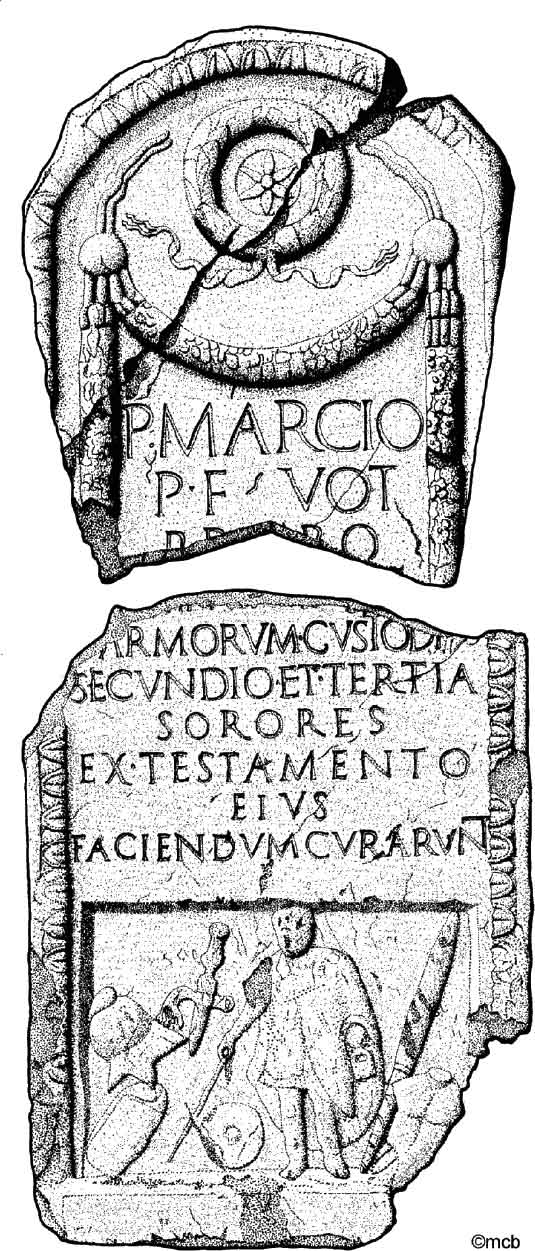

Stela of P. Marcius Probus, a custos armorum. He is shown wearing a paenula and carrying a staff of office and a book of writing tablets, both perhaps symbolic of his rank. Depicted around him are (clockwise from bottom left) a small round shield, a curved rectangular shield, a crested Italo-Corinthian helmet, a dagger and belt with straps and crescentic terminals, a bundle of shafted weapons (?), and a cuirass. Probably 1st century AD, from Bergamo, Italy (not to scale).

Second edition first published in the United Kingdom in 2006.

Reprinted 2009, 2011, 2013 and 2016 by

OXBOW BOOKS

10 Hythe Bridge Street, Oxford OX1 2EW

and in the United States by

OXBOW BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Road, Havertown, PA 19083

M.C. Bishop and J.C.N. Coulston 2006

Paperback Edition: ISBN 978-1-84217-159-2

PDF ISBN: 978-1-78570-397-3

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-78570-395-9

PRC ISBN: 978-1-78570-396-6

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset in Caslon by M.C. Bishop at The Armatura Press

Cover design by Andrew Brozyna of AJP Design

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher in writing.

Printed in the United Kingdom by Short Run Press, Exeter

For a complete list of Oxbow titles, please contact:

UNITED KINGDOM

Oxbow Books

Telephone (01865) 241249, Fax (01865) 794449

Email:

www.oxbowbooks.com

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Oxbow Books

Telephone (800) 791-9354, Fax (610) 853-9146

Email:

www.casemateacademic.com/oxbow

Oxbow Books is part of the Casemate Group

To Hazel, Martha, Oliver, and Christabel

For further details and supplementary material see www.romanmilitaryequipment.co.uk

Front cover illustration: Oberammergau dagger and sheath (photo: Archologische Staatssammlung, Mnchen)

Contents

Preface and Introduction

Before the first edition of this book, the last attempt to examine Roman military equipment from the Republic to the late Empire in a single, substantial volume was made by Couissin in 1926. Our 1989 booklet provided only a summary, within a very restricted format which precluded the use of references. Wishing to bring the field of Roman military equipment studies to a wider audience, the primary aim of the first edition of the present book was to demonstrate that the subject provides a window into the practical workings of the Roman army. Moreover, we believed that it could elucidate the place of soldiers and military institutions within Roman culture and society as a whole and thus have broad implications for an understanding of the Roman world. We have not been disappointed in this respect.

A study with the present title could either delineate and discuss separately the various classes of equipment (armour, shields, swords etc.), or it could adopt a more historical perspective. We have deliberately chosen the latter approach, not only because it enables us to explore various pertinent technological and sociological issues in their appropriate contexts, but also because it permits us to stand back and view the development of Roman equipment throughout our period.

We are aware that this is an ambitious project, but it is vital to attempt it because Roman military artefact studies have traditionally been subordinated to narrow art-historical discussions, or marginalized as typology-fodder.

It is a commonly held view that Romes rise to empire owed much to the efficiency and military skill of her armies. Often implicit in this opinion is the notion of Roman technical and technological superiority over barbarian adversaries. One of the purposes of the present book is to investigate just how advanced Roman military technology was in contemporary terms. Central to this are the origins of Roman equipment, its evolution, and the interrelationships between soldiers, the arms production industry and the wider society of which the army was just a part.

What is meant by the term military equipment? There is no general agreement amongst scholars and a definition is most easily formed in negative terms. There are grey areas within which objects could be either civilian or military, according to their context, which is only to be expected, since the Roman army included within its ranks many of the trades to be found in civilian life. Cart fittings are a case in point: soldiers used wagons and carts of various kinds, but these vehicles were not necessarily military in design. Fittings are found in both military and civilian contexts without distinguishing features.

Thus, there is little advantage in defining a rigid specification for what is, and is not, military equipment. Some readers may find our criteria to be arbitrary, but, for the purposes of the present volume, military equipment excludes the dona militaria, siege engines, draught harness and wagon fittings. Tools and clothing are only briefly discussed, whilst items of personal adornment, such as brooches, are generally omitted, except where they may act as representational evidence. On the other hand, we have sought to include standards and musical instruments for the first time, since further reflection has persuaded us that their role was fundamental to the operation of the Roman army.

The historical limits from the beginning of the 2nd century BC to the beginning of the 5th century AD accord with Romes rise to, and decline from, dominance in the Mediterranean world. They also coincide with the bulk of the published archaeological evidence: to have started earlier or continued later would have required not only more space, but also a radically different approach to the source material.

We have assumed that the reader has a basic knowledge of the Roman army and will refer to the standard texts. No apology is made for mixing modern and ancient place-names but we have endeavoured to be consistent, and the perplexed reader will find a map and topographical list immediately after this preface. In most instances, line illustrations have been used in preference to photographs because they are capable of conveying more information than a single photograph and it is easier to scale them accurately. We have been careful to reference facts wherever possible, whilst trying to keep the notes to a manageable size. We have also sought to avoid the pseudo-technical Latin terminology which abounds in publications on the Roman army.

A dozen years have passed between the publication of the first (1993) and second editions of Roman Military Equipment. This might not seem a great length of time compared, for example, with the gap between the first edition and Couissins 1926 study, but the pace of research has accelerated amazingly in recent years. It is not much of an exaggeration to assert that military equipment studies constitute one of the most exciting, dynamic and fast-changing areas within the broad field of Roman research. Eight Roman Military Equipment Conferences met before 1993, of which five were held in England; seven have been staged since 1993, no less than six of which have met on the continent. With each new national venue a new circle of archaeologists became directly involved, often realising that hitherto localised work had an extensive international audience. Each conference followed a chosen theme, such as Republican or Late Roman or barbarian equipment, but each also included sessions highlighting newly studied old finds or entirely new discoveries. Thus the conference series has been precisely geared to bring new people into a forum for new work. And the show goes on!

Next page