Contents

Guide

Also by Stephen P. Kershaw

The Search for Atlantis

THE ENEMIES OF

ROME

The Barbarian Rebellion

Against the Roman Empire

STEPHEN P. KERSHAW

THE ENEMIES OF ROME

Pegasus Books, Ltd.

West 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2019 by Stephen P. Kershaw

First Pegasus Books hardcover edition January 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

ISBN: 978-1-64313-310-2

ISBN: 978-1-64313-375-1 (Ebook)

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company

In memoriam Dorothy Kershaw, AUC 26812771

Contents

I owe a tremendous debt of gratitude to a great many individuals, groups and institutions without whose help, expertise and inspiration this book could never have been written. In no particular order, I would like to express my deepest thanks to many of my fellow ex-students and the brilliant teachers from Salterhebble County Primary School, Heath Grammar School (Heathens rather than barbarians) and Bristol University, without whose enthusiasm, dedication and know-how I would never have been able to engage with the ancient Romans, Greeks and barbarians, and their languages and culture. Among the many are Richard Sanderson, Alan Froggy Guy, Frank Haigh and Big Jimmy Feesh, who ignited and sustained my interest in Roman history, and J. G. McQueen, Richard Jenkyns, Brian Warmington, Thomas Weidemann, Niall Rudd, Jim Tester, John Betts and Richard Buxton, who generously gave of their enormous knowledge. Also important to the process are my colleagues and students (both real and virtual) at Oxford University Department for Continuing Education, European Studies, and the Victoria and Albert Museum, who, in their different ways, have facilitated my professional development in our explorations of the ancient world together. Credit must also go to all the fine people at Swan Hellenic, Cox & Kings, Learn Italy and Noble Caledonia, whose cultural itineraries have allowed me to explore the physical world of the Romans and barbarians in so much style. On the publishing side I give my heartfelt thanks to Duncan Proudfoot, Rebecca Sheppard, Howard Watson, Oliver Cotton and David Andrassy for their professional excellence in putting this book together. Underlying all this is the rock-solid support that my late parents, Philip and Dorothy Kershaw, gave me throughout my career, the love and understanding of my wife Lal, and Heros faithful, and occasionally barbaric, canine companionship.

On the north wall of the Basilica in Pompeii there is a piece of graffiti that reads:

L. ISTACIDI AT QVEM NON

CENO BARBARVS ILLE MIHI EST

Lucius Istacidius: he, at whose place

I do not eat, is a barbarian to me.

Also at Pompeii, in house V.2.1, there is a metrical, but pretty well meaningless, scribbling that was probably used to teach someone how to write hexameter poetry:

BARBARA BARBARIBVS BARBABANT BARBARA BARBIS

Barbaric things bearded barbarically with barbaric beards.

But what makes Lucius Istacidius seem barbarian, and what makes things and people barbaric in Roman eyes? Are all barbarians barbaric, in the modern sense of being primitive, wild, uncivilised, uncultured, and/or violent? Can barbarians be heroic? Can highly civilised people be barbarians? Should we be drawing clear-cut binary distinctions between Romans and barbarians, and between Romanness and barbarity? Did Romans and barbarians need those distinctions to define themselves?

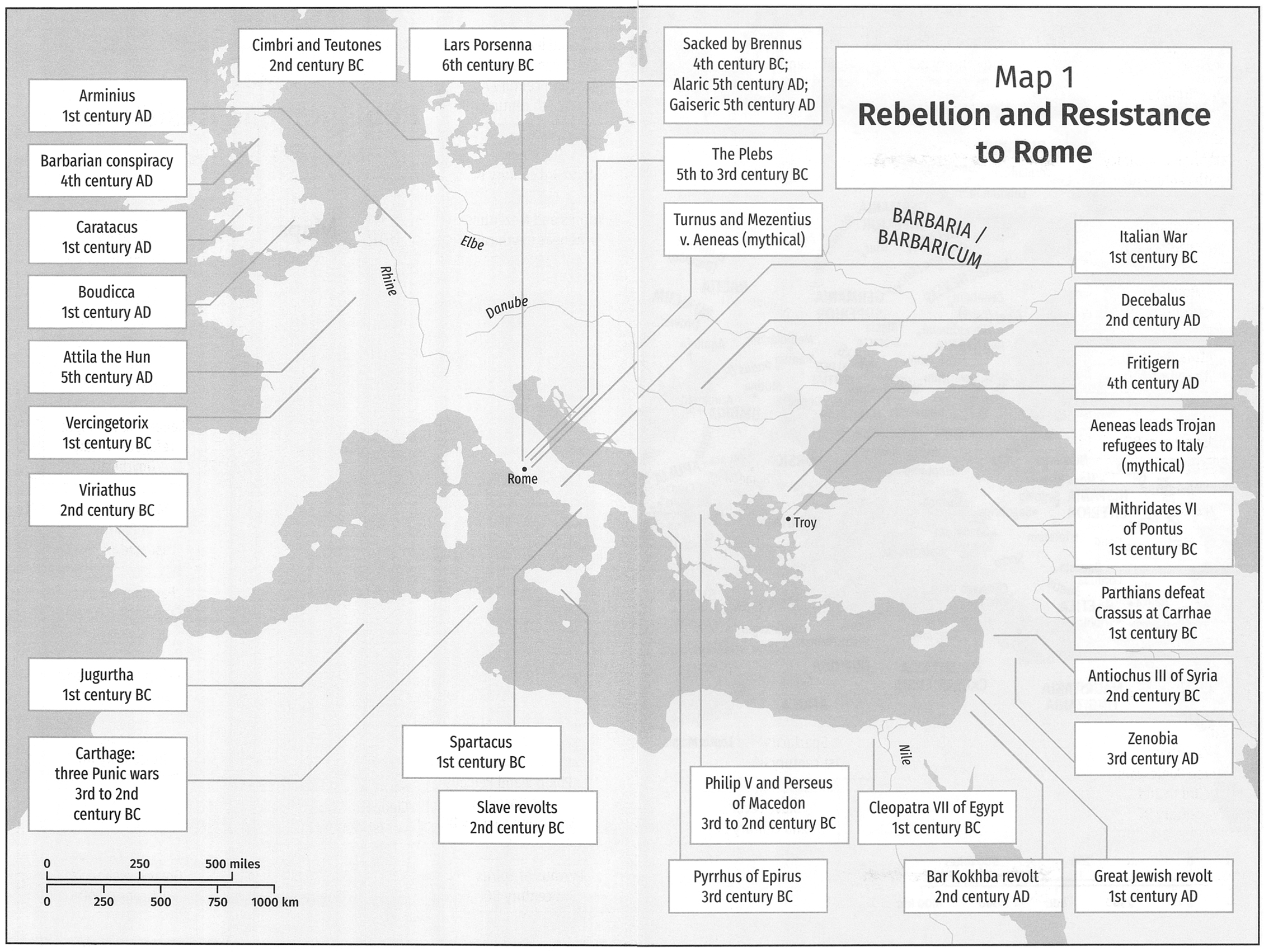

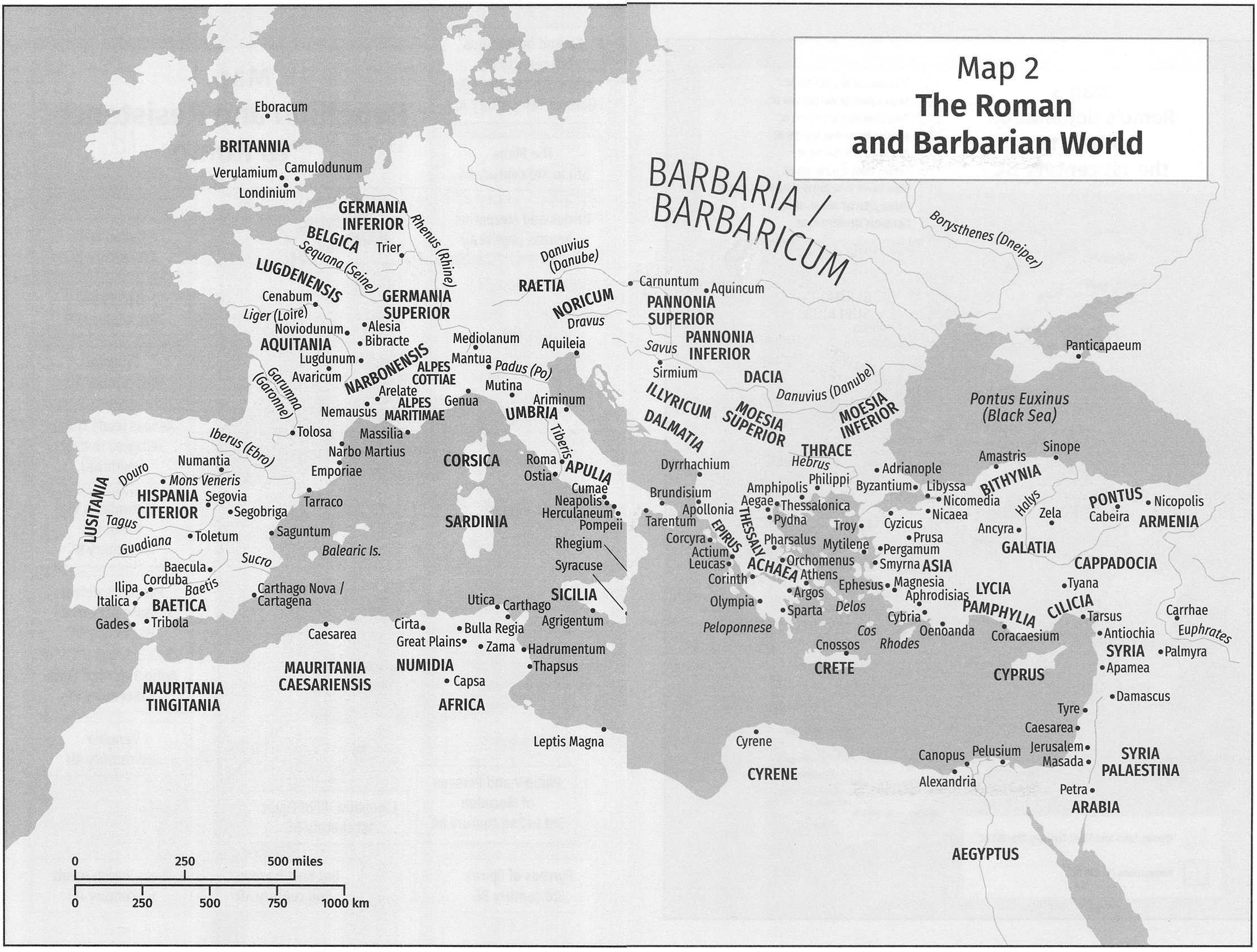

Further questions then arise: Were barbarians hostile to Rome by default? How unified were the barbarians? Was there a pan-barbarian identity? What might the import or imitation of Roman products that we find in Barbaricum or Barbaria (the area outside the Roman Empire) tell us about barbarian attitudes to Rome? Did the Romans have barbarians on their mind, and were they obsessed with barbarophobia to the extent that is often imagined? Overall, barbarity is complex, and Roman responses to it are equally so.

The Romans inherited the word barbarus , which can be a noun (a barbarian) and an adjective (barbarous), from the Greek barbaros . This may have been in use as far back as the Bronze Age, where the word pa-pa-ro is used to signify a barbarian outsider, in this case someone not from Pylos where the document was written. not because the people of Lesbos didnt speak Greek or because the island was felt to be outside the boundaries of the Greek world, but because it was hard to understand.

Other ancient languages have similar words: Babylonian-Sumerian uses barbaru for foreigner, and there are several Indo-European words for incomprehensible speech, including balbutio in Latin (= I stammer, stutter, babble, lisp, speak obscurely/indistinctly), blblati (to stammer) in Czech, and possibly baby in English. So, originally, it was speech that defined the barbarian as against the Greek: no other ancient people privileged language to such an extent in defining its own ethnicity. in other words, the barbarian is defined by the Greek, and vice versa.

The Greek attitude changed as a result of the Persian invasions by Darius I and Xerxes I in 490 and 480479 BC. The Greeks invented the idea of the barbarian

In due course, the Romans adapted the term in order to refer to anything that was non-Roman. There is irony here, in that, as far as the Greeks were concerned, the Romans themselves were technically barbarians. But the Romans chose to focus more on the behavioural than the racial implications of the word, at least when it suited them, and made a wholesale cultural appropriation of the Greek idea. To be truly civilised, you had to live not in the savagery of the natural environment on the fringes of the world, but at its centre: