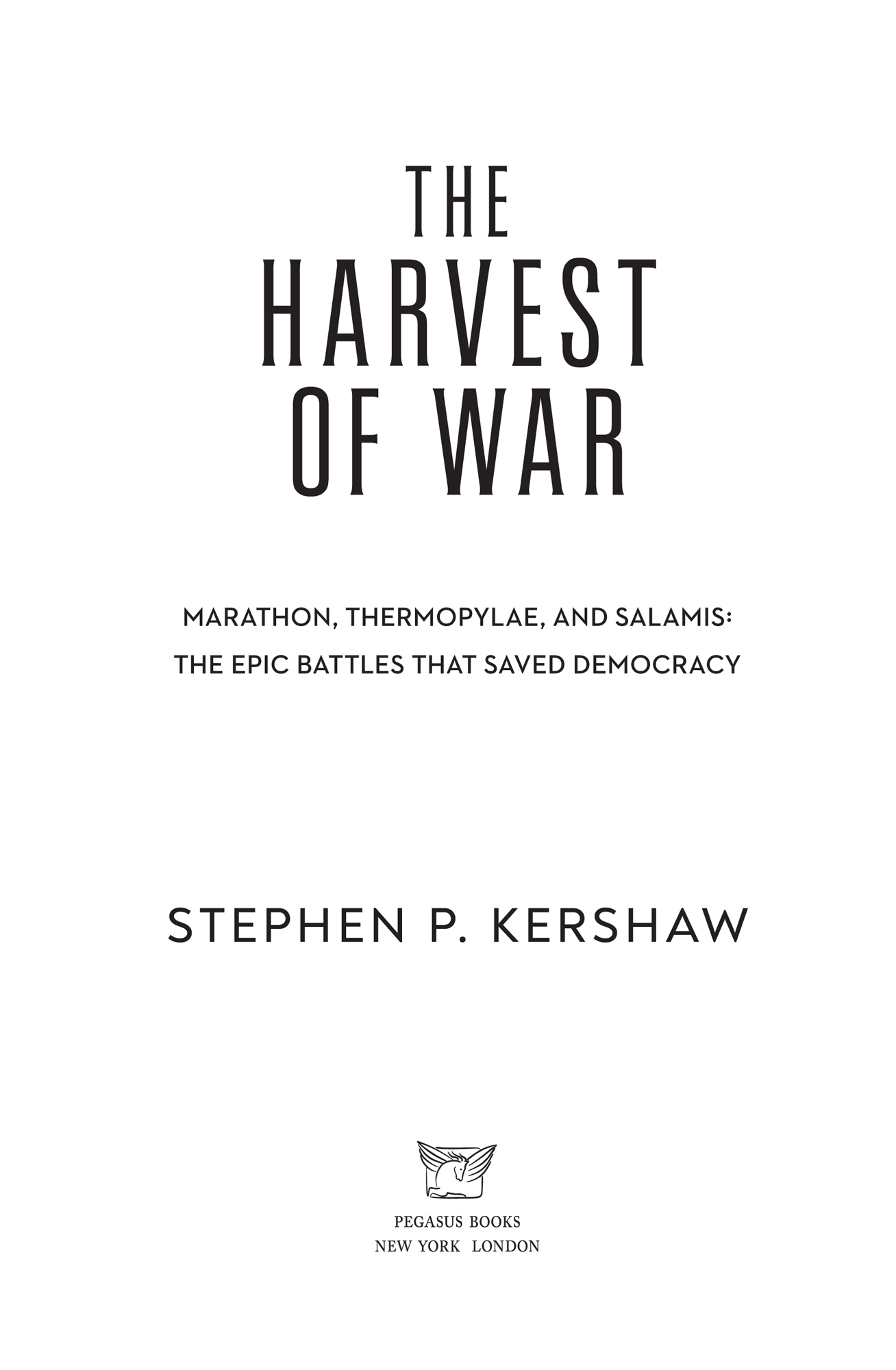

Stephen P. Kershaw - The Harvest of War: Marathon, Thermopylae, and Salamis: The Epic Battles that Saved Democracy

Here you can read online Stephen P. Kershaw - The Harvest of War: Marathon, Thermopylae, and Salamis: The Epic Battles that Saved Democracy full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: New York, year: 2022, publisher: Pegasus Books, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Harvest of War: Marathon, Thermopylae, and Salamis: The Epic Battles that Saved Democracy

- Author:

- Publisher:Pegasus Books

- Genre:

- Year:2022

- City:New York

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

The Harvest of War: Marathon, Thermopylae, and Salamis: The Epic Battles that Saved Democracy: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Harvest of War: Marathon, Thermopylae, and Salamis: The Epic Battles that Saved Democracy" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

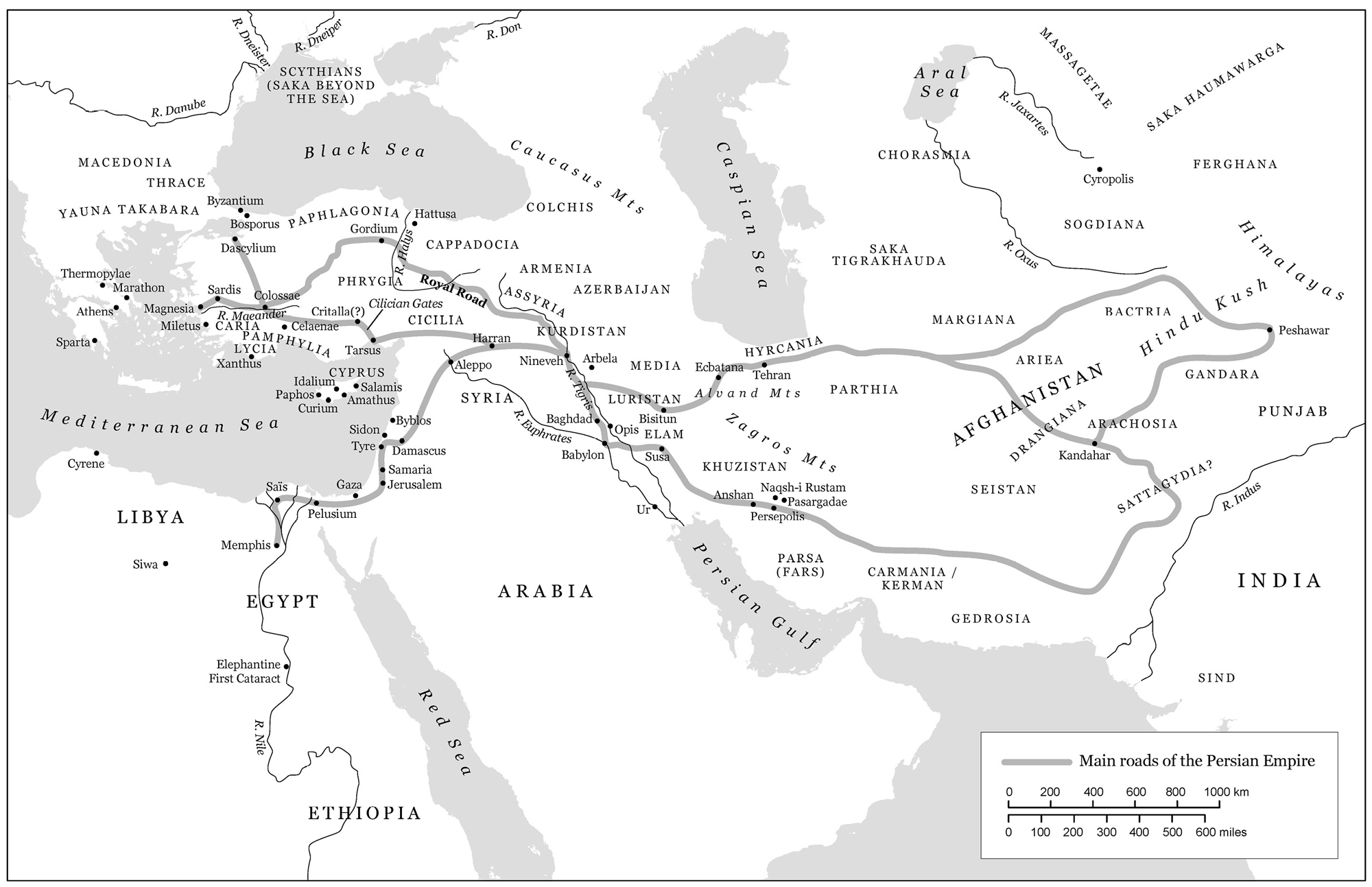

In 2022 it will be 2,500 years since the final defeat of the invasion of Greece by Xerxes, the Persian king. This astonishing clash between East and West still has resonances in modern historyand has left us with tales of heroic resistance in the face of seemingly hopeless odds. The Harvest of War makes use of recent archaeological and geological discoveries in this thrilling and timely retelling of the story, originally told by Herodotus, the Father of History.

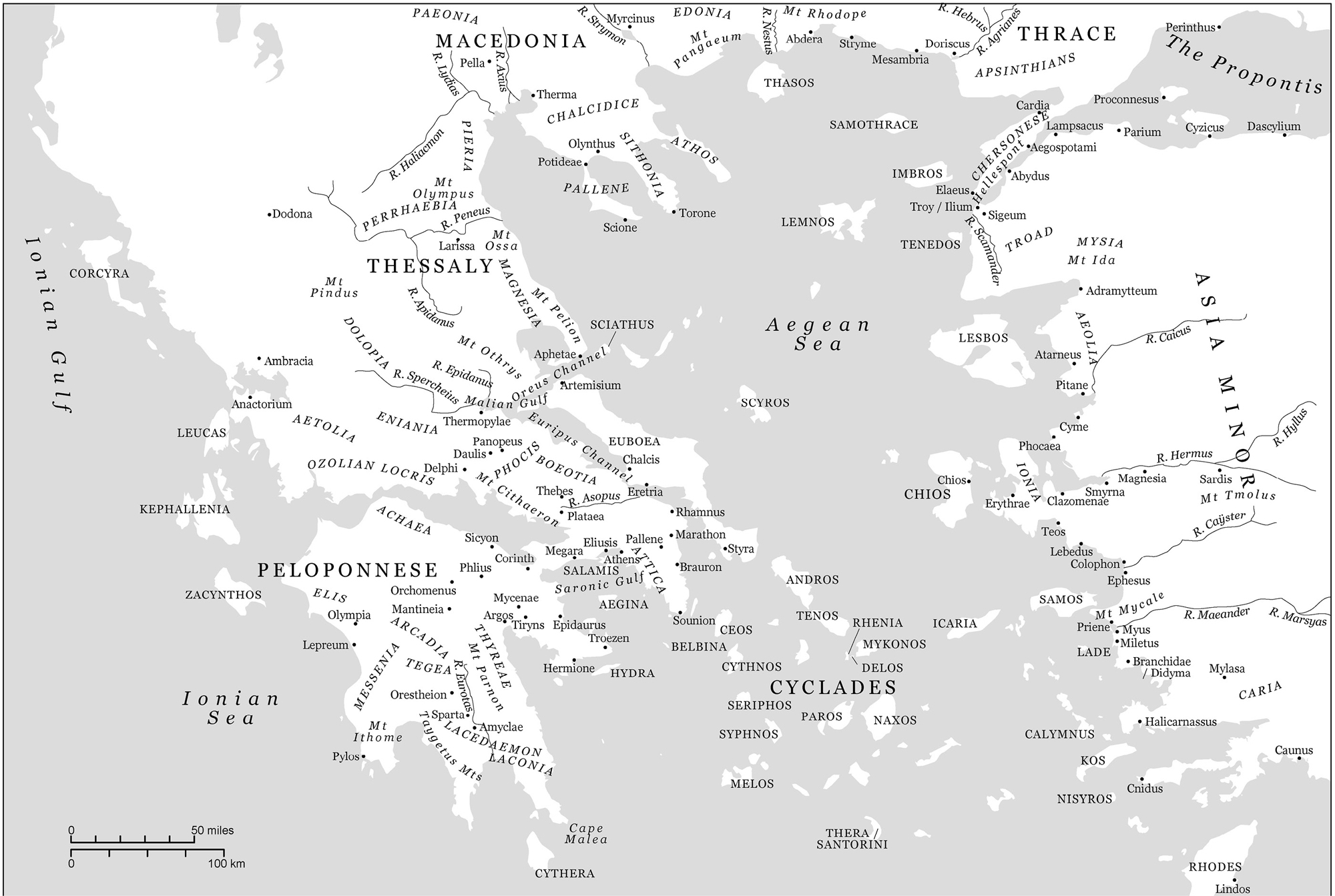

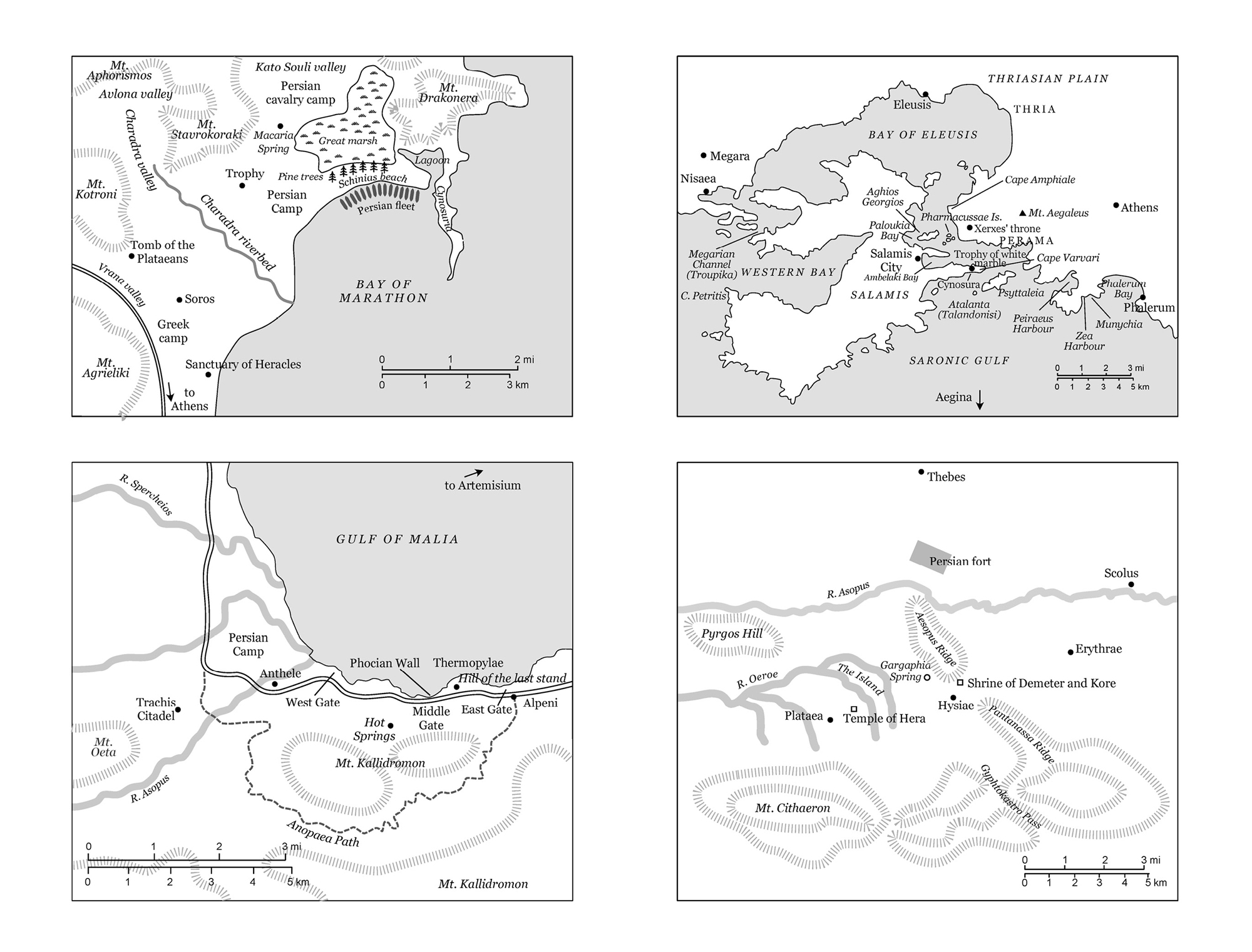

In 499 BC, when the rich, sophisticated Greek communities of Ionia on the western coast of modern Turkey rebel from their Persian overlord Darius I, Athens sends ships to help them. Darius crushes the Greeks in a huge sea battle near Miletus and then invades Greece. Standing alone against the powerful Persian army, the soldiers of Athens newly democratic statea system which they have inventedunexpectedly repel Dariuss forces on the planes of Marathon.

After their victory, the Athenians strike a rich vein of silver in their state-owned mining district, and decide to spend the windfall on building a fleet of state-of-the-art warships.

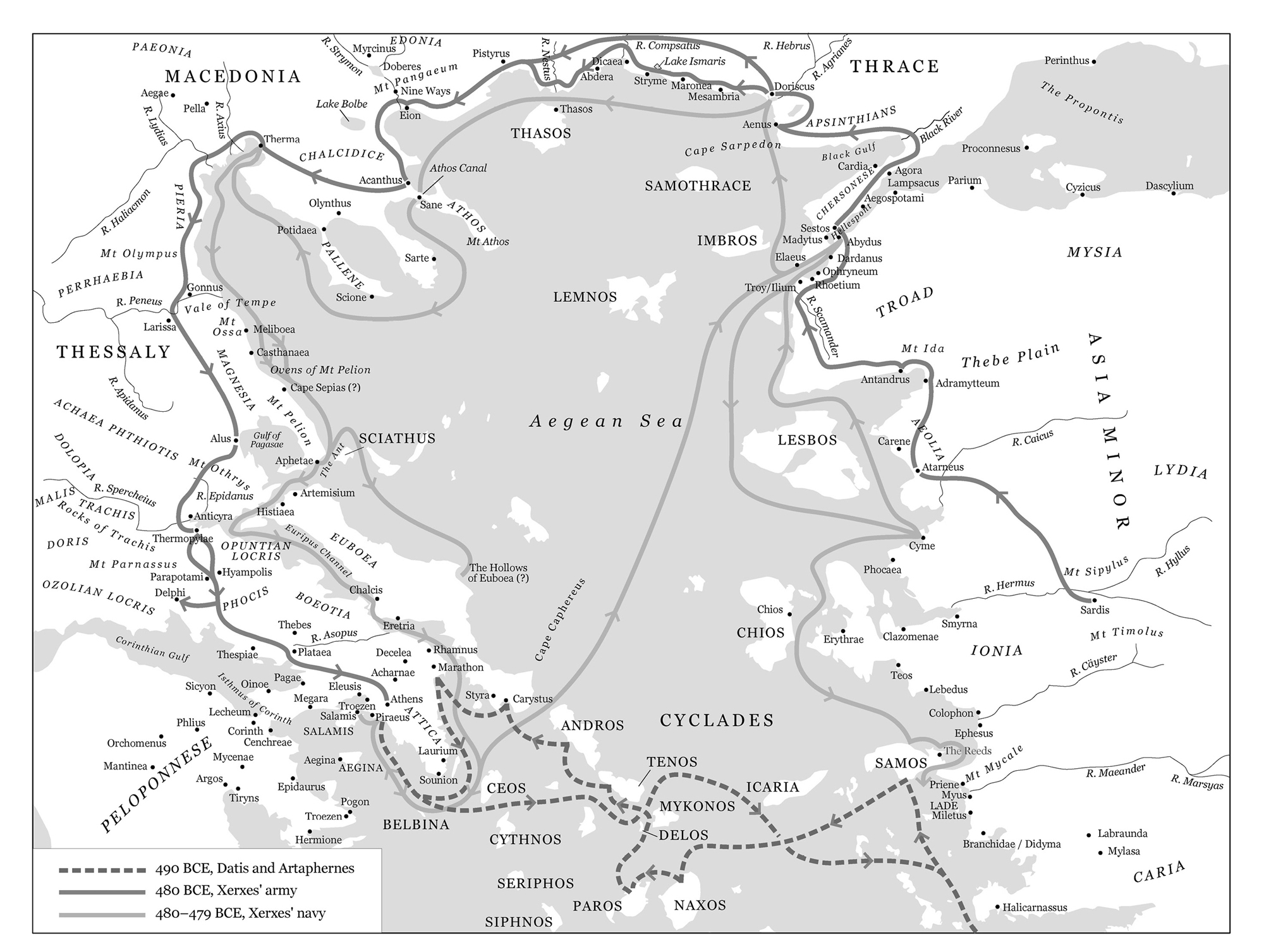

Persia wants revenge. The next Persian king, Xerxes, assembles a vast multinational force, constructs a bridge of boats across the Hellespont, digs a canal through the Mount Athos peninsula, and bears down on Greece. Trusting in their wooden walls, the Athenians station their ships at Artemisium, where they and the weather prevent the Persians landing forces in the rear of the land forces under the Spartan King Leonidas at the nearby pass of Thermopylae. Xerxess assault is a disastrous failure, until a traitor shows him a mountain track that leads behind the Greeks. Leonidas dismisses the Greek troops, but remains in the pass with his 300 Spartan warriors where they are overwhelmed in an heroic last stand.

Athens is sacked by the Persians. Democracy is hanging by a thread. But the Athenians convince the Greek allies to fight on in the narrow waters by the island of Salamis. Despite the heroism of the Persian female commander Artemisia, the Persian fleet is destroyed.

The Harvest of War concludes by exploring the ideas that the decisive battles of Marathon, Thermopylae, and Salamis mark the beginnings of Western civilization itselfand that Greece became the bulwark of the Westrepresenting the values of peace, freedom, and democracy in a region historically ravaged by instability and war.

Stephen P. Kershaw: author's other books

Who wrote The Harvest of War: Marathon, Thermopylae, and Salamis: The Epic Battles that Saved Democracy? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.