ROMES

GREATEST

DEFEAT

ROMES

GREATEST

DEFEAT

MASSACRE IN THE TEUTOBURG FOREST

ADRIAN MURDOCH

First published in 2006 by Sutton Publishing

This edition published by The History Press 2008

Reprinted in 2009, 2010, 2012

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

Adrian Murdoch, 2008, 2013

The right of Adrian Murdoch, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9455 5

Original typesetting by The History Press

For Susy

Contents

Maps

Family Trees

INTRODUCTION

This Savage Forest

B ones were all he could see. Although the German soil had reclaimed most of the traces, he was standing in the remains of what had been a marching camp. The ditches had slowly silted up and weeds had grown back over the boundaries and the forts streets. Not even the charred traces of campfires had survived. Six years previously three legions, three cavalry battalions and six auxiliary units had died around here. Some 14,000 men had been wiped out in a matter of days.

It was dangerous, an indulgence almost, to come here. It had been a brutal and gruelling year. He and his legions had been on campaign since the spring. He had first seen off the Chatti, a tribe that lived in what would become the state of Hesse, razing their capital and destroying their farmland. Then he had savaged the area around Mnster in a combined cavalry, infantry and marine assault that had paralysed the enemy.

And now, in the early autumn of AD 15, he was here. In his minds eye he could see how the surviving cavalry and infantry had formed up in the cutting rain under the barbarian onslaught, as their colleagues built some protection. He could hear the trumpets of the heralds blasting out orders and centurions shouting at legionaries as they constructed a marching fort; tough veterans trying to rally shaken groups of soldiers with that same mixture of humour and contempt common to every army, doing anything to keep their minds off what could happen. It was the might of the Roman army working like clockwork, manoeuvres that every soldier present would have practised many, many times before.

He only had four legions with him today. His deputy, Aulus Caecina Severus, was currently patrolling the surrounding area with another four legions as planned. With any luck they should have been reconnoitring for ambushes, checking the passes and making the swamps and waterways safe with bridges and causeways.

He rode on. Ahead the second redoubt the word camp was too generous spoke of dying men and of desperate and hurried construction. All that remained was a partially collapsed rampart and a shallow ditch. This could not contain three legions; it was space for hundreds, not thousands of men. This was the place for a last stand. The field was strewn with the remains of men. Some skeletons lay on their own, some in clusters, their bones now whitened and impersonal. Yet even after five German summers it was still obvious that the legionaries lay where they had fallen, some making a last stand, others caught trying to escape.

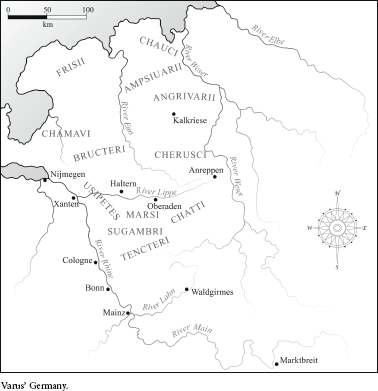

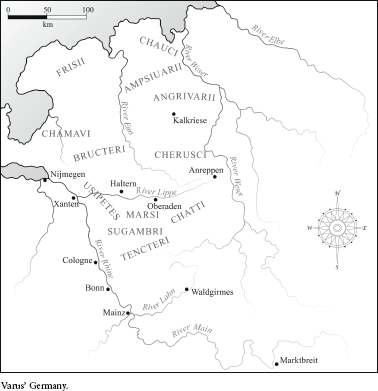

It was the perfect spot for an ambush, this unforgiving German landscape, along the main westeast road from the mid-Weser to the safety of the Roman camps and nascent towns on the lower Rhine. Near the remains of the camp he could see the 6km-long narrow pass, the via dolorosa along which Legions XVII, XVIII and XIX had marched to their deaths. The army had been funnelled along an uneven and difficult path, clogged with drifting sand and only 200m wide in places, with the oak- and beech-lined Kalkriese Mountain to one side, the waterlogged Great Moor on the other.

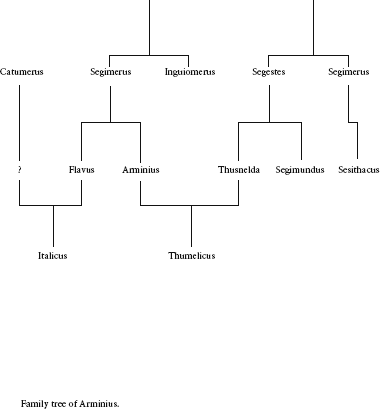

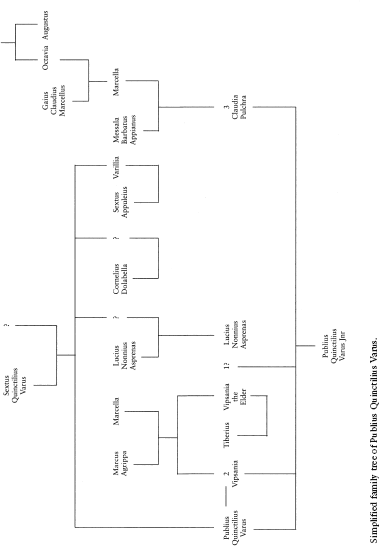

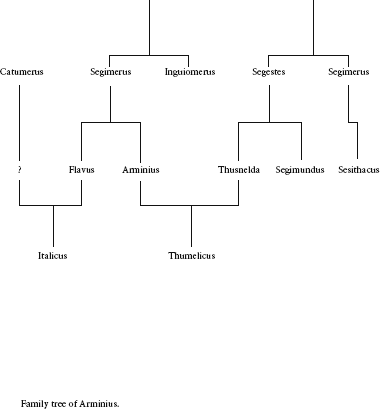

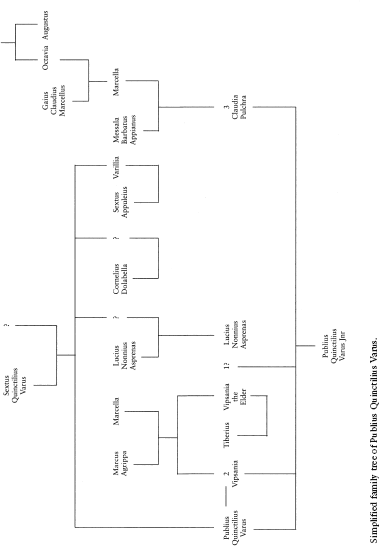

Some of the survivors of the disaster showed their commander around. They pointed out the stained and scorched altars. It was here that the Germans, under the command of the turncoat Arminius, had burned the tribunes and first-rank centurions alive. They reported, blow by blow, how the three eagles, Romes military standards, had been captured. They pointed out where senior officers had been killed. This is where Numonius Vala was cut down from his horse while trying to make a break for the river; that is where Ceionius surrendered once he realised that there was no chance for survival; over here is where Lucius Eggius was killed. And then they re-enacted Publius Quinctilius Varus final moments. This is where the architect of this disaster, the governor of Germany had first been wounded, where he had taken his own life, and finally where his adjutants had buried him.

It was his successor, Germanicus, who now stood deep within German territory. The governor of Upper and Lower Germany, commander of eight legions, adopted son of the Emperor Tiberius and heir to the Roman Empire had come on a pilgrimage, to try and lay to rest the shame of Rome, to exorcise some ghosts and to pay his last respects. The greatest emperor that Rome would never have, had to see it. His soldiers had to see it.

This expedition to the battlefield of the Varian disaster would earn Germanicus an official imperial reprimand. Romans, unlike Christians, did not sanctify death. His very presence at a mass grave, at a German sanctuary, was inappropriate and inauspicious for one of Romes most senior priests. More seriously, the remains of the makeshift gibbets from which Roman soldiers had been hanged, the pits into which still-living infantry men had been thrown, the skulls nailed to nearby trees were not an appropriate sight for Roman legionaries. It could be too much of a blow for morale and make them slow to fight. The visit was opening up old wounds that were, at any rate, barely healed.

To Germanicus and his men, the battlefield looked like the one-sided slaughter that it had been. He could see no trace of German corpses nor any of their weapons. Like the ancient Spartans, Germans came back with their shields or on them. The Germans who had fallen in battle were long since buried at home. If he had spotted it, an iron spur with a small, spiked wheel that lay on the battlefield was certainly of native design, but had the German auxiliary cavalry soldier who had lost it fought for Romans or had he fought for Arminius?

Next page