For my parents

Thanks are due to Tony Morris for the inspiration to return to my Roman Republican roots, and to Rob Boddice, Michael Fronda, Marianne Goodfellow and Stephanie Olsen for reading drafts and offering their advice and corrections.

Copyright notices

Thank you to the following for their excerpts used in this text:

Polybius, Books 18: reprinted by permission of OUP from Polybius, Histories , trans. Robin Waterfield with introduction and notes by Brian McGing (Oxford, 2010).

Polybius, Books 915: Polybius, The Histories , vol. 4, Loeb Classical Library 159, trans. W.R. Paton, rev. F.W. Walbank (Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press 2011).

Appian, Book 10: Appian, Roman History , vol. 2, Loeb Classical Library 3, trans. H. White (Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press 1912).

Diodorus, Book 29: Diodorus Siculus, Library of History , vol. XI, Loeb Classical Library 409, trans. F.R. Walton (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press 1957).

Plutarch, Life of Pyrrhus : Plutarch, Lives , vol. 9, Loeb Classical Library 101, trans. B. Perrin (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press 1920).

Loeb Classical Library is a registered trademark of the President and Fellows of Harvard College.

All other translations are by the author.

Contents

Please note: all dates are BC , unless otherwise stated.

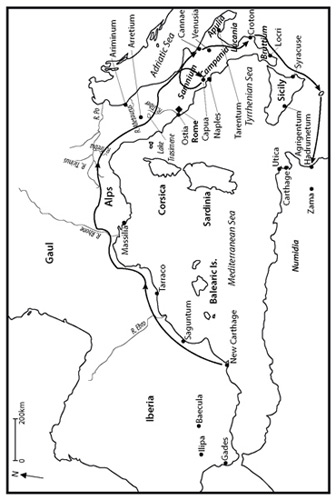

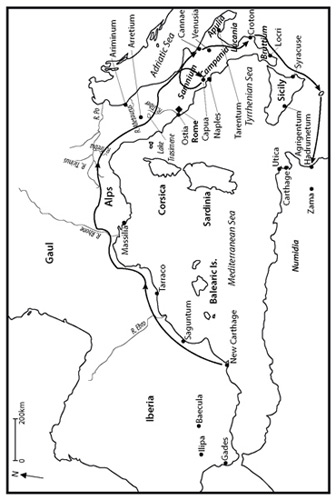

The western Mediterranean in the time of the Hannibalic War. The arrow marks Hannibals journey. (Illustration by Aaron Styba)

Romans

The Scipio Family

(1) Publius Cornelius Scipio, consul 218, father of Scipio Africanus

(2) Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio, consul 222, brother of (1)

(3) Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus, consul 205 and 194

(4) Lucius Cornelius Scipio Asiaticus, brother of (3)

(5) Publius Cornelius Scipio Aemilianus, grandson by adoption of (3), patron of Polybius

It is anachronistic to call (3) Africanus before 201; to avoid confusion (1) and (2) are called the elder Scipios or the Scipio brothers and (3) the younger Scipio.

Other Leaders

Aemilius Paullus, consul 216

Cato the Elder, enemy of the Scipios

Claudius Nero, consul 207

Crispinus, consul 208

Fabius Maximus, dictator in 217

Flamininus, conqueror of Macedonia

Flaminius, consul 217

Fulvius Flaccus, general

Laelius, lieutenant of Africanus

Livius Salinator, consul 207

Marcellus, killed 208

Marcius, Roman commander in Spain

Minucius, Fabius second in command

Sempronius, consul 218

Servilius, consul 217

Silanus, lieutenant of Africanus

Tiberius Gracchus, son-in-law of Africanus

Varro, consul 216

Carthaginians

The Barcid Family

(1) Hamilcar Barca, father of Hannibal; died in Spain, 228

(2) Hasdrubal The Fair, son-in-law of (1); killed 221

(3) Hannibal, son of (1), invader of Italy

(4) Hanno, nephew of (3)

(5) Hasdrubal, brother of (3), general; killed 207

(6) Mago, brother of (3), general; died 203

Other Leaders

Bomilcar, general

Hanno, anti-Barcid politician

Hasdrubal, son of Gisgo

Marhabal, lieutenant of Hannibal

Other Major Figures

Antiochus III The Great, King of Syria

Archimedes, mathematician

Edeco, Spanish nobleman

Eumenes II, King of Pergamum

Hieronymus, anti-Roman King of Syracuse

Indibilis, rebellious Spanish chief

Mandonius, rebellious Spanish chief

Massinissa, Numidian king

Philip V, King of Macedonia

Prusias I, King of Bithynia

Pyrrhus of Epirus, Greek warrior king

Syphax, Numidian king

Introduction

I am about to tell the story of the most memorable war of any ever fought the war that the Carthaginians, under the leadership of Hannibal, waged against Rome.

Livy, 21.1

For nearly all of its 500 years in existence, the Roman Republic was at war. The most famous of all these conflicts was the marathon struggle for supremacy with Carthage between 264 and 146 BC . The principal act of this rivalry was the so-called Hannibalic War or Second Punic War (218202), which was dominated by two generals: Hannibal Barca of Carthage and the Roman aristocrat Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus.

Carthage, a Phoenician (in Latin, Punic) colony, was based around the city of the same name, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Tunisia. At various times Carthage commanded broad swathes of territory across the North African coastline and extended its influence to the islands of the Mediterranean. The Roman Republic, created in c. 509 when the last king of Rome was ejected, had emerged from its humble beginnings as a small village to dominate most of the other communities of Italy. Both states had a powerful aristocracy, and both possessed a formidable military reputation.

The Hannibalic War was Romes first major Mediterranean conflict. Its generals, soldiers and diplomats saw action over a vast area, including Spain, Macedonia, Greece, Africa, Italy and Sicily. Narrowly escaping extermination in 216, the Romans finally emerged triumphant in 202 after one of the most improbable revivals in military history. This resurgence showed the Mediterranean world the power of Roman arms, laying the foundation for one of the most critical events in world history; with Carthage humbled, Rome steadily conquered the Mediterranean and built an empire that lasted, in various guises, for well over 1,000 years.

The Hannibalic War is filled with courageous deeds, disastrous exhibitions of hubris, and larger-than-life characters. A number of Roman generals, such as Marcellus, Fabius Maximus, Claudius Nero and the elder Scipios, helped Rome to recover from the depths of despair. On the other side, Hannibals brother Hasdrubal and another Hasdrubal, son of Gisgo, together with a number of others, won important victories and earned the praise of the historians who chronicled their deeds. Despite the existence of all of these great figures, Hannibal and Scipio have remained the most famous actors in the story. The second-century BC historian Polybius called the Romans true athletes of warfare, Scipios successes on the battlefield gave him an unrivalled military reputation, and his contributions in Spain made Romes triumph possible.

Hannibal and Scipio are examples of great individuals: those who, by sheer force of character, their ability to lead and understand the men around them, and their self-belief, courage and political stamina, change the course of history. They have left an indelible impact in the annals of human endeavour as illustrations of the heights of success that personal determination can bring. Their effect on history can also be measured in the way they inspired others. Hannibals tactics encouraged generations of military leaders, including such luminaries as Napoleon Bonaparte. Scipios place as the most famous Roman hero of the Republican era later earned his name a place in Italys national anthem and (less enviably) as a poster boy in Mussolinis revival of Italian power in the 1930s. In the film Scipione lafricano (director C. Gallone, 1937), Scipio (played by the suitably named Annibale Ninchi), triumphing over the African Carthaginians, was used to justify Italian imperialist ambitions in Africa. Both men have often been taken out of their historical context and used for a whole host of purposes, a feat made possible only by the brand recognition they earned from their deeds in antiquity.