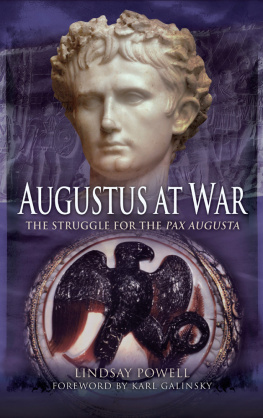

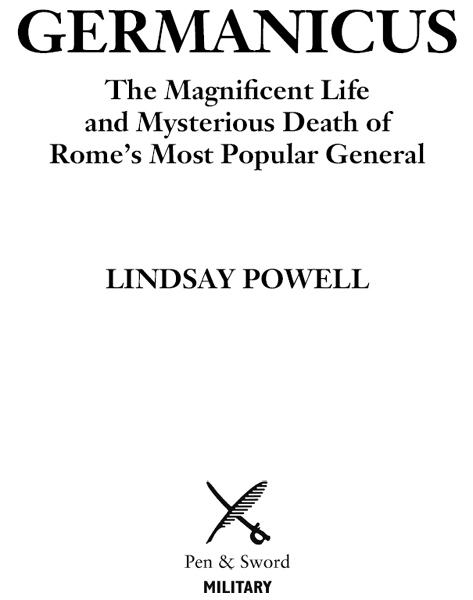

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by

PEN & SWORD MILITARY

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Lindsay Powell, 2013

HARDBACK ISBN: 978-1-78159-120-8

PDF ISBN: 978-1-47383-093-6

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-47382-692-2

PRC ISBN: 978-1-47382-648-9

The right of Lindsay Powell to be identified as the author of this work has been

asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in

any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying,

recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without

permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset by Concept, Huddersfield, West Yorkshire.

Printed and bound in India by Replika Press Pvt. Ltd.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation,

Pen & Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military,

Pen & Sword Discovery, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe True Crime,

Wharncliffe Transport, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics,

Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and

Frontline Publishing.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

For my Mother,

Valerie Powell.

Fin caru ti .

Contents

by Philip Matyzsak

Foreword

by Philip Matyzsak

The early years of the Roman empire constitute one of the most fascinating periods in history. There exists almost no other period before the early modern era where we have so much information about a particular society. And the thing about the early modern era is that (almost by definition) many of the values and viewpoints of western society were coming into alignment with those of today.

This is not the case with the early imperial period. Here we find a society largely untouched with ideas of chivalry, Judeo-Christian ethics, and even concepts such as romantic love which form the background to our emotional lives, just as technology and medicine have changed our material lives. Yet despite the huge cultural gap between ancient Rome and that of the modern west, we find ourselves drawn to the emotion, pathos and epic drama which filled the lives of the early Caesars. The stories from this era are timeless. They deal with ambition, betrayal, family feuds and violent twists of fortune, often mixed with mystery, intrigue and flamboyant sexuality.

Of the above, all that detracts from the story of Germanicus is the fact that unlike his adoptive father Tiberius all that is reported of the sex life of Germanicus is that he was happily married to a loving wife who blessed him with a regular supply of offspring. (Many of whom did not survive tragically, childhood in antiquity was more dangerous than military service.)

In fact there is little in the life of Germanicus that would not make an inspiring tale in one of the Boys Own magazines of a century ago. Our man was heroic, yet compassionate, intelligent yet sympathetic and if charisma could be bottled, Germanicus would have had enough to corner the entire Mediterranean market. The ancient sources tell us of his energy on the campaigns which he commanded with flair and success. Of how Germanicus personified vengeful Rome after the treacherous destruction of three Roman legions in the Teutoburg forest, and how he stopped a mutiny of the Rhine army by the sheer force of his personality.

Then there is the tragedy of the young heros mysterious death in the east. Was he killed by illness or malice? Did misfortune or a devious plot bring the career of Romes most promising general and politician to its abrupt halt? Here at last we find the whiff of scandal which this dramatic tale has heretofore been lacking.

Yet something else has been lacking from the story of the best emperor that Rome never had and that is a critical examination by a modern historian. There was indeed another side to the legend of Germanicus had anyone cared to look for it, and by the standards of today that side is pretty dark. After the massacre of the legions in the Teutoburg forest, the problem for a Roman general was not to defeat the Germans in battle, but to bring them to fight that battle in the first place. Germanicus achieved this by conducting vast punitive operations over the Rhine which spared neither age not sex. In other words, Germanicus massacred women and children in the hope of provoking their menfolk into fighting.

Nor were those operations without cost to Rome. Gambling that his armies could be transported by sea despite the proven failure of Roman naval technology in that regard, Germanicus repeatedly and recklessly rolled the dice that put his men at peril upon the sea and finally lost most of his army. Many of the promises made to the (justifiably) mutinous Rhine legionaries were broken or quietly forgotten afterwards.

For reasons such as these, the life and strange death of Germanicus require reexamination by an impartial historian today. Impartiality is needed for another reason that the most factually trustworthy historian of the Roman empire, Cornelius Tacitus, blatantly and viciously slanted those facts against Tiberius, the adoptive father of Germanicus. In the works of Tacitus, one seldom reads of Tiberius acting except through selfishness, jealousy or ruthless political calculation. From a reading of the Annals , one is forced to the conclusion that Tiberius bitterly resented the brilliance and popularity of his appointed successor, and schemed to limit and tarnish these at every opportunity. From Tacitus, one might assume that the jealousy and conservatism of Tiberius were largely to blame for the failure to assimilate Germania into the Roman empire, and Germanicus was yanked from his command just as the realization of that objective appeared possible.

It is a dramatic story but is it true? At a distance of almost 2,000 years it takes painstaking research to separate fact from fiction, and drama from reality, and all too often the effort is futile. This is particularly true of the Julio-Claudians, a family who combined for contemporaries the modern cult for pop and film celebrities and the enduring fascination with the private life of royalty. One can read descriptions of senatorial debate, and inscriptions which survive on buildings, dedications and statuary, yet the decisions which affected the course of the Roman empire and the fate of its leaders were generally taken in private chambers and closed family discussions. It is impossible to know what was said on such occasions, but that did not stop ancient writers from guessing. And where the facts failed, they did not shy away from wholesale invention.

For all these reasons a modern, impartial study of the life of Germanicus is not only timely but overdue. For, apart from the enduring mystery of his death, Germanicus did come as close as anyone in the attempt to re-establish Roman rule from the Rhine to the Elbe. Had he succeeded, the history of the Roman empire and therefore of subsequent ages would have been greatly different. It is worth examining how and why the attempt failed, and learning more about the man who made it.

Philip Maty Matyzsak