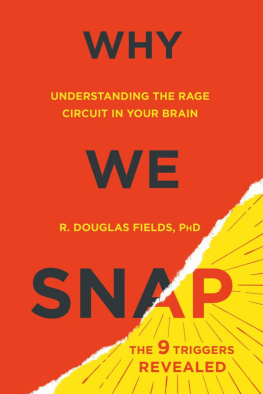

Copyright 2015 by R. Douglas Fields

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

DUTTONEST. 1852 (Stylized) and DUTTON are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Names: Fields, Douglas.

Title: Why we snap : understanding the rage circuit in your brain / Douglas Fields.

Description: New York : Dutton, 2016. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015016464 | ISBN 9780525954835 (hardback) | ISBN 9780698194311 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Anger. | Violence. | Neurosciences. | BISAC: SCIENCE / Life Sciences / Neuroscience. | MEDICAL / Research.

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, Internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

1

Snapping Violently

Rage is a short madness.

Horace, Book 1, Epistle ii, line 62

Y ou mustnt say things about Melanie, he warns her.

Who are you to tell me I mustnt? she snaps back, vibrating in anger. You led me on. You made me believe you wanted to marry me!

Now, Scarlett, be fair, he pleads, trying to calm her fury. I never at any time

You did! Its true! You did. She cuts him off. Ill hate you till I die! she screams. I cant think of anything bad enough to call you!

Sobbing in rage, she suddenly slaps her lover across his face. As he retreats she grasps a vase and hurls it across the room. The delicate porcelain shatters against the wall.

Later the jilted woman sobs desperately as the second man in her lovers triangle walks out on her: Oh, Rhett! Rhett, Rhett! Rhett... Rhett, if you go, where shall I go? What shall I do?

He faces her calmly and delivers these enduring words: Frankly, my dear, I dont give a damn.

Gone with the Wind, the 1939 film classic based on Margaret Mitchells novel, captures the paradoxical moment of snapping that is familiar to us all, but inexplicable. Why smash a treasured vase? Why slap a lover across the face? The immediate aftermath brings regret and shame, and upon reflection bewilderment. The explosive impulse of destruction is driven by a powerful righteous rage, overwhelming but pointless.

Who has not lost self-control in a blind rage, smashing a dishor worse? We all wish to believeneed to believethat we are in control of our behaviors and actions, but the fact is that in certain instances we are not. Something unexpected in our environment can unleash an automatic and complex program for violence, destruction, and even deathall of it an unconscious pre-established program.

Rage explodes without warning. Overpowering judgment, compassion, fear, and pain, the fiery emotion serves one purposeviolence, both in words and actions. While this human response has been vital to our survival since our species evolved, rage simultaneously puts ones life at risk. And it seems there is no escaping the rage circuit once it has been activated. So if rage is an automatic reflex, are you really in control of your fate? That flare-up with your partner or child or friend or even a complete stranger can change your life in an instant, forever.

Despite the essentially peaceful lives most of us lead most of the time, killing is programmed into the human brain. This is because, as with most animals, individuals in the natural world must be able to defend themselves and their offspring. Moreover, carnivores must kill other living creatures for food. These behaviors are hardwired in the brain, not in an area where consciousness resides but instead deep in the core of the brain where other powerful impulses and automatic life-sustaining behaviors (feeding, thirst, and sex) are programmed. Each of these behaviors, just like the complex rage behavior, is automatic once triggered. The question is, what triggers this deadly switch for violence and killing?

Late one summer night in a torrential downpour, my daughter and I threaded our way through the dark cobblestone back alleys of Paris, hungry and lost. Like most scientists, I travel the world to lecture and collaborate with other scientists, and I almost always travel alone. This night my seventeen-year-old daughter was with me. The springtime of proms, graduation ceremonies, and anxious anticipation of leaving high school behind had cleared a momentary opportunity for a father and daughter to share time together. It was wonderful seeing Kellys eyes open to the world. Soaking wet, we leaped over puddles and escaped into a steamy one-room restaurant. No one spoke English. Kelly applied her high school French to order from one of the three frantic middle-aged women who shared the burden of all the cooking and serving.

Suddenly in exasperation the woman jabbed at the menu, scolding Kelly. She had not ordered a glass of wine for herself. The idea that anyone would enjoy a fine dinner without the requisite glass of wine was unthinkable. For Kelly, underage for drinking alcohol in the United States, this was a revelation. Not everywhere in the world is necessarily the same as the place in which you were reared.

After Paris we traveled to Barcelona for my next lecture at an international meeting of neuroscientists. The morning before the meeting began we made a quick visit to the Gaudi cathedral. Ascending the steps out of the dingy subway station smelling of concrete dust and sweat, we emerged into the brilliant Barcelona sun. The crowd of passengers pressed upon us in a gray blur.

Suddenly I felt a sharp tug at my pant leg. As if swatting a mosquito I slapped the zippered pocket above my left knee. My wallet was gone!

My left arm shot back blindly. In a flash I clotheslined the robber as he pivoted to hand my wallet to his partner and flee down the steps. As if swinging a sledgehammer I hurled him by his neck over my left hip and slammed him belly first onto the pavement, where I flattened him to the ground and applied a head lock.

Splaying my legs for hip control like a wrestler pinning an opponent I yelled for help. Fifty-six years old, 130 pounds, with wire-rimmed glasses and graying hair, I have no martial-arts training, no military experience, no background in street fighting. Drawing on junior high school wrestling moves from forty years ago, I found myself applying an illegal choke hold. The street-smart hoodlum struggling in my arms was in his late twenties or early thirties.