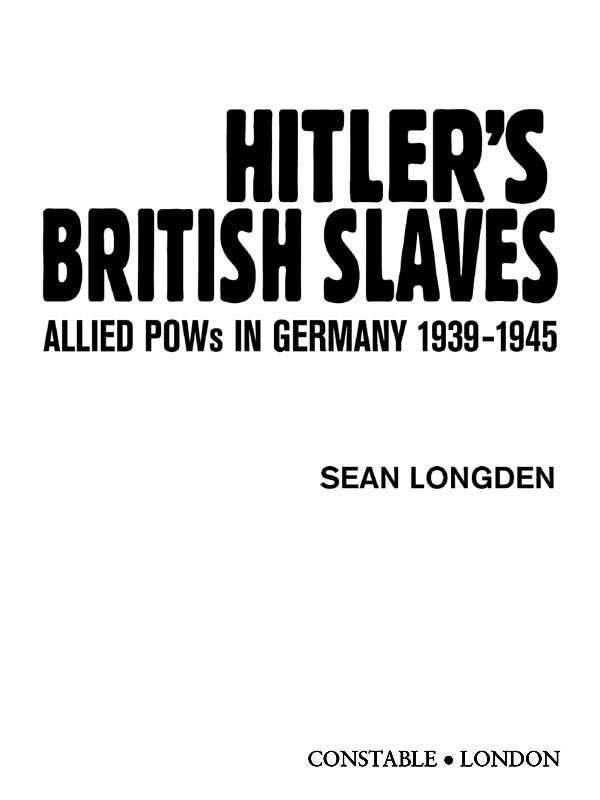

SEAN LONGDEN studied East European history at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University of London. After graduation he worked in photographic archives and press agencies. His first book, To the Victor the Spoils, will be published this year by Constable and Robinson Ltd. He is married with two children and lives in Surrey.

Also by Sean Longden

To the Victor the Spoils

Constable & Robinson Ltd

3 The Lanchesters

162 Fulham Palace Road

London W6 9ER

www.constablerobinson.com

First published in hardback in the UK by Arris Books,

an imprint of Arris Publishing Ltd 2005

This paperback edition published in the UK by Constable,

an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd 2007

Text copyright Sean Longden 2005

Map by John Taylor

The right of Sean Longden to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-84529-519-6

eISBN 978-1-47210-359-8

Printed and bound in the EU

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

List of illustrations

Acknowledgements

There are many people without whom this book would not have been possible. My thanks must go firstly to Bill Sykes, the D-Day veteran and ex-POW whose thoughtful communications from his home in California contributed much to this book. Thanks must also be given to Les Allan, the founder of the National Ex-POW Association. Les has campaigned long and hard for the sufferings of European prisoners of war to be fully recognized by the British government. I only hope this book can help contribute to a wider understanding of the subject and possibly play some small part in their sufferings being acknowledged.

Gordon Barber and Ken Willats both provided vital details about life on farms in East Prussia. Even now, sixty years later, they remain close friends and helped colour this book with so many vivid tales. Bryan Willoughby kindly shared his tales of the battles in Arnhem and his subsequent experiences as a prisoner. Thanks must also go to Sandi Toksvig for inviting me onto her radio show to discuss my previous book, To the Victor the Spoils. This resulted in Alec Reynolds contacting me to tell his tales of working in the copper mines of the Third Reich. Thanks must also go to the wives of the men I interviewed, all of whom showed such great hospitality.

My thanks go to Maurice Newey, Kenneth Clarke, James Witte and Eric Laker, all of whom gave me permission to quote from their memoirs held in the Imperial War Museum. Thanks are also due to Mrs R. Eltringham, A.J. Richardson and Anne Turner who gave me permission to quote from the memoirs of their fathers, also now held in the Imperial War Museum.

Thanks must also be given to the board and trustees of the Imperial War Museum, and to the staff in both the Department of Documents and in the photographic archive whose assistance was priceless. I must also extend my gratitude to Helen Pugh and Ipsita Mandal at the Red Cross who helped me access the albums of photographs taken by the Red Cross at the work camps and Stalags across occupied Europe. Many of these are included within this book. Bryan Willoughby, Gordon Barber and Bill Sykes also kindly allowed me to use their treasured photographs within the book. As ever the staff of the National Archives in Kew provided a highly efficient service in finding all the necessary documents. Thanks must also be given to the individual at the Ministry of Defence who decided that the POW debriefing questionnaires should finally be made available to the public. The release date was just in time for me to be able to include these documents in my research.

My thanks also go to Steve Cawthorne who contacted me following the publication of the hardback edition of this book. He informed me that his uncle William Slade was not killed whilst in captivity (originally cited in chapter 7). Instead, he and his comrades, Laurence Kavanagh and Norman Cullity, survived a firing squad. I apologise to Mr Cawthorne and his family for any hurt my error has caused and I wish to extend my gratitude to him for correcting my error.

I must also offer my gratitude to Geoff, Victoria, Bethan and Beth. Last, but not least, I must thank my wife Claire who has been so understanding when I spent so many hours sat in front of the computer.

Preface

Hitlers British Slaves? That is the correct title, its a true description. A slave is someone who is made to work under threat to his life. If a slave tries to run away he is killed. He isnt paid. He is at the will of his masters. It was the same for us. We were given a bowl of soup and some bread made from sawdust. If you didnt do as you were told you were shot. Therefore it was slavery.

Leslie Allan, founder of the National Ex-Prisoner of War Association.

There is an impression of World War Two prisoner of war camps that is forever engraved in the imagination of the public. In this mythologized version of events the camps are perceived as institutions whose atmosphere and conditions were like a mixture of a severe boarding school and a strict holiday camp. This was an image created by the books and films that emerged in the aftermath of war with their stereotypes later reinforced by television series and comedy shows. From Eric Williamss classic tale The Wooden Horse, first published in 1949, through to the 2005 television drama Colditz, the public have been fed a stream of misleading information. These were tales of heroism, evasion and escape of tunnels, expert lockpickers, forgers and masters of disguise. The image was fostered of resolutely middle class officers staging escapes with devil may care bravery, anxious to get home ready for another crack at the Hun.

In this myth incarceration was an unwanted interruption to wartime service and escaping a matter of honour to be approached with the levity of boarding school boys sneaking out of the dorm to indulge in a forbidden cigarette. Their clothes were clean, their hair groomed and their chins shaved. These were men who read books, produced plays, listened to camp orchestras, made themselves cricket nets from the string from Red Cross parcels and studied for professional exams.

This life did exist, it is part of the story but not the whole story. Missing from this story are the experiences of the vast mass of prisoners. In short, the mythical POW camp ignores all ranks except officers. Although the POW camp of fiction could be recognized by many former officer prisoners as a sanitized version of their experiences, for those other ranks unlucky enough to experience the Stalags and work camps little comparison could be made. Left out of this rosy picture of POW life are the men who toiled in the farms, factories and mines of the Reich the men who swept the streets of German cities and cleared its bombsites. These were the men who marched hundreds of miles into captivity, who survived on starvation rations and faced casual violence from their guards. These forgotten men were forced to manufacture munitions for the enemy and were used as slave labour to build the factories of Auschwitz. Twelve-hour shifts, often seven days a week, were the norm. Watery soups and hard, dry bread was their diet. Often clad in rags and shod in clogs, the prisoners of war were the forced miners, builders, farm labourers and quarrymen of the Third Reich, slaves to Hitlers dream of European domination.

Next page