Gilbert - POW : allied prisoners in europe 1939-1945

Here you can read online Gilbert - POW : allied prisoners in europe 1939-1945 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: S.l, year: 2014, publisher: Thistle Publishing, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

POW : allied prisoners in europe 1939-1945: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "POW : allied prisoners in europe 1939-1945" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

POW : allied prisoners in europe 1939-1945 — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "POW : allied prisoners in europe 1939-1945" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Pow

Allied prisoners in

Europe 19391945

Adrian Gilbert

All Rights Reserved

This edition published in 2014 by:

Thistle Publishing

36 Great Smith Street

London

SW1P 3BU

www.thistlepublishing.co.uk

To Louis, and to Rosie and Freya

Adrian Gilbert

Adrian Gilbert has written extensively on military history. Among his books are World War One in Photographs; Britain Invaded, an imaginary account of a cross-channel German invasion in 1940; The Imperial War Museum Book of the Desert War, featuring firsthand accounts from British and Commonwealth forces in North Africa, 194042; and Sniper: One-on-One, a history of sharpshooting and sniping.

Contents

Illustrations

Section One

Section Two

Photographic credits: I, Sipho; 2, US Air Force Academy McDermott Library; 3, J. H. Witte; 4, 11, Mary Tagg; 5, Marc and Francesca Vietor; 6, Linda and Rob Prouse; 7, B. A. James; 8, Mrs LeFevre; 9, 10, 16, 18, 19, 25, 26, 28, 29, 32, 34, Imperial War Museum; 12, 14, 27, H. C. M. Jarvis; 13, 15, 21, 30, Museum & Archive, British Red Cross Society; 17, author's collection; 20, C. Whitcombe; 22, 23, Jonathan Goodliffe; 24, W. Stephens; 31 American Red Cross; 33, PNA.

Preface

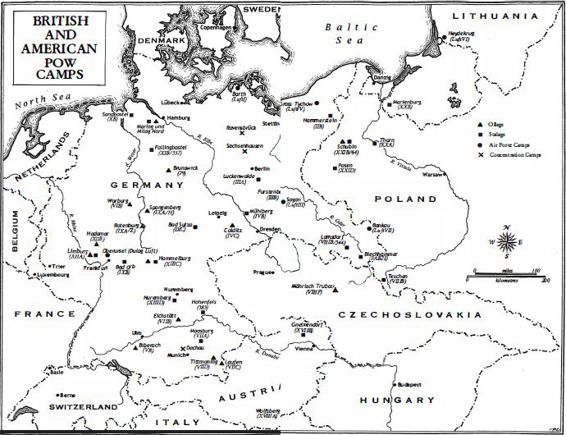

A PPROXIMATELY 295,000 BRITISH and American servicemen were captured by the Axis forces of Germany and Italy during the Second World War. A precise number for British, Commonwealth and Empire POWs in Europe seems impossible to obtain; estimates for the three armed forces and the merchant marine range from 170,000 to 200,000 men, although the higher figure seems most likely. POW figures for the United States are more certain, however: around 95,000 soldiers and airmen were imprisoned by the Axis. Whereas most American prisoners were captured relatively late in the war the majority entering captivity in 1944 the British suffered several major defeats in the first half of the conflict, with the bulk of their prisoners being captured between 1940 and 1942. Consequently, the British were the long-stay detainees who tended to set the tone of the Anglo-American POW experience.

British and American prisoners enjoyed a special status within the prison camps of Germany and Italy. Their homelands had not been overrun by the Axis unlike those of many other Allied prisoners and, as the war progressed, Britain and the United States accumulated ever-increasing numbers of enemy prisoners; the Germans and Italians were aware that the fate of their own men in captivity was largely dependent on the care of the British and American prisoners under their control.

But if the treatment of British and American prisoners was better than that experienced by other POWs, captivity was still a wretched business. The gung-ho escape narratives that came to define prison life in the post-war years give a false gloss to the drab realities of existence behind barbed wire: poor living conditions, chronic sometimes acute hunger, deadening monotony, and the misery of being beholden to the will of the enemy with no release date in sight.

Despite the fundamentally negative nature of POW life, there were positive aspects that sprang from the prisoners' own determination to make the most of their otherwise poor lot. Escape and sabotage were obvious ways of fighting back against the enemy, but there were other, more oblique, means adopted by prisoners to maintain a sense of purpose and dignity. Imprisonment provided men with an opportunity to develop their artistic and intellectual potential. One enterprising music-lover even commissioned the composer Benjamin Britten to write a choral piece for a prison-camp music festival. Others continued their education, with several thousand taking academic and professional examinations that were set and marked in Britain and the United States.

Scattered like islands across Greater Germany and Italy, POW camps were small havens of civilization and democracy within a totalitarian sea. In most camps men were elected by ballot to positions of authority and responsibility; free speech was taken for granted; books prohibited beyond the wire were read by those within, and for the first time in years the music of a banned composer like Mendelssohn could be heard in Germany. Prisoners of war displayed an inspirational fortitude in enduring and sometimes overcoming their circumstances.

For the sake of convenience I have used the term 'British' to include British, Commonwealth and Empire forces, except where a distinction needs to be made. And I have followed the POWs' practice of calling Soviet prisoners 'Russians', although many came from different nationalities within the Soviet Union. Also for convenience's sake I have used the general expression 'other ranks' to include both NCO and private ranks.

In a book that reflects the diversity of experiences of captivity in Germany and Italy, I have had the good fortune to be able to draw upon an array of source material and information held in institutions and supplied by individuals. In Great Britain I must acknowledge the invaluable help provided by the Imperial War Museum, with its treasure trove of documentary and audio materials, and the National Archive (Public Records Office) at Kew. Also of great help were the National Ex-Prisoner of War Association, the London Library, the British Library, the Second World War Experience in Leeds, the Monte San Marino Trust, and the libraries of the Wiener Institute and University College London. In Australia I would like to thank the Australian War Memorial for its help. In the United States I am grateful for the assistance provided by the US Military History Institute at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and the US Air Force Academy Library, Colorado, and to the American Ex-Prisoners of War (AXPOW) organization.

Among the individuals who helped me in my researches are A. D. Azios, Bill Bunbury, Professor Lewis H. Carlson, Cheryl Cerbone, Dr Arthur A. Durand, Dr Jerry Flack, Peter Hart, Professor Milan Hauner, Joseph O'Donnell, William O'Neill (and Jean Sax), John Reis, Pina Saccone, Brigadier S. C. Sharma (Military Adviser, High Commission of India), Peter Stanley, Martin Sugarman and Patricia Wadley. My thanks to them all.

I owe a special thanks to the copyright holders of the unpublished first-hand narratives that appear in this book. They include the Australian War Memorial (Douglas LeFevre), Squadron Leader B. A. James, A. C. Howard, Linda and Rob Prouse (A. Robert Prouse), William and Sebastian Stephens (W. L. Stephens), Mary Tagg (Revd R. G. McDowall), Francesca and Marc Vietor (John A. Vietor) and J. H. Witte.

Every effort has been made to clear permissions. If permission has not been granted please contact the publisher, who will include a credit in subsequent printings and editions.

I am grateful to the following authors, publishers and agents for allowing me permission to quote from the following works: We Were Each Other's Prisoners by Lewis H. Carlson (Basic Books); The Anti-Warrior: A Memoir by Milt Felsen (University of Iowa Press), A Crowd is Not Company by Robert Kee (Sphere, 1989), represented by David Higham Associates; A Terrier Goes to War by Jim Robert (Minerva); Wars and Rumors of Wars by Roger L. Shinn (Abingdon Press).

My thanks also to my agent, Andrew Lownie, who made this project happen, to Roland Philipps and Rowan Yapp at John Murray, and to Bob Davenport and Martin Collins.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «POW : allied prisoners in europe 1939-1945»

Look at similar books to POW : allied prisoners in europe 1939-1945. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book POW : allied prisoners in europe 1939-1945 and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.