For Fang Fang

and William

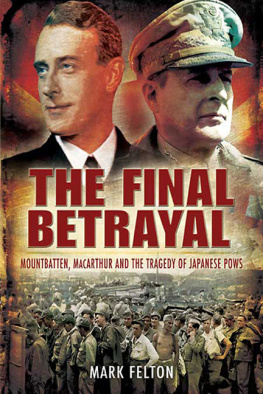

First published in Great Britain in 2012 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Mark Felton, 2012

9781783032624

The right of Mark Felton to be identified as Author of this Work

has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical

including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and

retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in 11/13pt Palatino by

Concept, Huddersfield, West Yorkshire

Printed and bound in England by

CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CRO 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword

Aviation, Pen & Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen &

Sword Military, Pen & Sword Discovery, Wharncliffe Local History,

Wharncliffe True Crime, Wharncliffe Transport, Pen & Sword Select,

Pen & Sword Military Classics, Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press,

Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Acknowledgements

I should like to express my gratitude to the following individuals, institutions and organisations who have given so freely of their time in answering my questions and aiding my research for this book. Many thanks to Lieutenant-Colonel Jonathan Knowles of the Royal Army Ordnance Corps Association; Justin Saddington of the National Army Museum; Michael Hurst, MBE, the Director of the Taiwan POW Camps Memorial Society; Rod Suddaby and Simon Offord at the Imperial War Museum in London. My particular thanks go to Pat Wang and the Mukden Prisoner of War Remembrance Society which has managed to preserve the remnants of the Mukden Camp as an excellent and informative museum with the assistance of the Chinese authorities in Shenyang. Shelly and Sue Zimbler of the Mukden Survivors & Descendants Group have been wonderful, and I should like to thank them very much. The assistance of Ron Taylor and the Far East Prisoners of War Association has been, as usual, invaluable during the course of researching this book, and both you and your organisation have my warmest gratitude. Many thanks also to Maurice Christie, author of Operation Scapula. My wife Fang Fang has acted as a brilliant research assistant and translator during the course of this project, enabling the Chinese side of the Unit 731 debate to be more fully explored, and Chinese academics and writers consulted. She did all of this in the midst of her busy career as well as finding the time to listen to my many ideas and theories, and has helped me to stay focused during the gestation of this book. Many thanks to Shirley Felton who has acted as an unpaid research assistant in Britain and tracked down innumerable published sources and very kindly sent so much material to me in Shanghai. Finally, my warmest thanks to Brigadier Henry Wilson, Matt Jones for all their hard work on this project and the excellent team at Pen & Sword Books, and my editor Sue Blackhall.

Introduction

We removed some of the organs and amputated legs and arms. Two of the victims were young women, 18 or 19 years old. I hesitate to say it but we opened up their wombs to show the younger soldiers. They knew little about women it was sex education.

Unit 731 veteran Akira Makino, March 2007

With their breath streaming like smoke into the freezing air, a small group of American prisoners bundled up in winter coats and caps, stacked the bodies of their comrades like cordwood in a long wooden hut. The bodies had been wrapped in dirty sheets and taken directly from the camps rudimentary hospital to the storeroom. There they would reside for the remainder of the harsh Manchurian winter and be denied a Christian burial on the orders of the Japanese camp commandant. Something unseen was stalking the prisoners at Mukden Camp, a collection of dilapidated Chinese barracks that had been turned into a temporary prisoner-of-war camp by the Japanese in 1942; an as yet unidentified disease that was carrying off American inmates with horrific regularity. Each day the senior British officer in the camp, Major Robert Peaty, concealed himself quietly inside his bunk and carefully recorded the numbers of deceased, normally between one and three young men a day. The men had all developed severe diarrhoea, had sickened and died quickly. Peaty had also noted the strange visits to the camp by teams of Japanese doctors, and the barrage of hypodermic injections all the nationalities inside the camp had received.

Come the spring, and the same team of American prisoners who had gently placed their dead comrades bodies into winter storage on the orders of the Japanese, were now told to bring the defrosted cadavers out of the hut and place them carefully on to a table that had been set up under the crisp spring sunshine. The naked bodies were unwrapped and carefully examined by murmuring Japanese Army surgeons. Without preamble, incisions were made, organs removed and samples carefully marked, as the Allied prisoners stood silently watching this final desecration of their dead. Once the autopsies were complete, the bodies were finally released for burial and the Japanese medical personnel left the camp with their grim specimens carefully logged in glass jars and phials. But the deaths inside the camp continued, and whatever was killing the Allied prisoners at the Mukden Camp continued its microbial work in silence as Major Peaty continued to note in pencil each daily fatality in his secret diary.

In China today there is a place that is so loathed and hated. Located in the northern city of Pingfan near Harbin in Heilongjiang Province, a place that has come to sum up for many Chinese the true face of the Japanese aggression that was unleashed against the nation seventy years ago. It ranks alongside the massacre memorial hall located in the busy city of Nanjing as representative of all the sufferings heaped upon the Chinese people by Imperial Japan between 1931 and 1945. It also remains as one of the great stumbling blocks between China and Japan ever reaching a true entente in the twenty-first century. It is a collection of sturdy red-brick buildings that carries the most infamous three-number identifier in history Unit 731.

The buildings at Pingfan are the remains of a gigantic experiment in biological and chemical warfare conducted by the Japanese military in occupied Manchuria. Many thousands of innocent people, from babies and young children, to adults of several nations, a list that has consistently included rumours of Allied prisoners-of-war, were put to death at the Pingfan facility in the name of science. Japanese military doctors, with the assistance of the Kempeitai military police, were permitted to conduct every sort of medical experiment on live human beings; experiments that are normally proscribed by law, morality and political and public revulsion. They were as free to play with lives in order to further scientific understanding as the most notorious of the SS doctors in the Nazi concentration camps, to push the boundaries of our understanding of human beings, and of human resistance to disease, infection and extremes of temperature, altitude and privation.