For Fang Fang and William,

my family

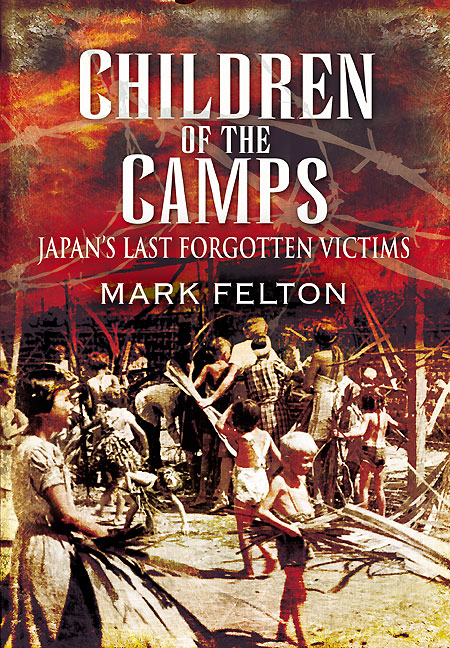

First published in Great Britain in 2011 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Mark Felton, 2011

ISBN: 978-1-84884-261-8

ePub ISBN: 9781844684120

PRC ISBN: 9781844684137

The right of Mark Felton to be identified as Author of this Work

has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical

including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and

retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in 11/13pt Palatino by

Concept, Huddersfield, West Yorkshire

Printed and bound in England by

CPI UK

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword

Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe

Local History, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics,

Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and

Frontline Publishing.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Acknowledgements

Many individuals and organisations have assisted me in creating this book and you all have my thanks and appreciation. Many thanks to the following: Ron Bridge, AFC, chairman of the Association of British Civilian Internees Far East Region (ABCIFER); David Parker, OBE, Director, Information and Secretariat, Commonwealth War Graves Commission; the historian and expert on the civilian internment camps in China, Greg Leck; Peter Hibbard MBE, President of the Royal Asiatic Society, Shanghai; Jill Durney and her wonderful team of archivists at the MacMillan-Brown Library, University of Canterbury, New Zealand; Ron Taylor and the members of the Far East Prisoners of War Association (FEPOW); The Children Of Far East Prisoners Of War Association (COFEPOW); The National Archives (Public Record Office), Kew, and the National Archives and Record Administration (NARA) in Washington DC. My gratitude and thanks to Brigadier Henry Wilson and all of the team at Pen & Sword Books, and in particular my editor Jan Chamier, as well as Jonathan Wright, Helen Vodden and Jon Wilkinson. To my wife Fang Fang, who has made me the writer that I am today through her love, encouragement, and support, I can only say thank you.

Introduction

I could walk down our barrack past women and children with broken teeth and bleeding gums, hair growing in tufts and faces and stomachs bloated with hunger oedema and beriberi, boils as big as ping pong balls and oozing tropical ulcers and not let myself see them: pain was pain.

Ernest Hillen, Dutch child internee

Kampong Makassar Camp, 194445

There must be at this stage be no thought of saving the troops or sparing the population. The battle must be fought to the bitter end at all costs Commanders and senior officers should die with their troops. The honour of the British Empire and of the British Army is at stake. I rely on you to show no weakness or mercy in any form.1 These words were penned by a British Prime Minister and represent one of the harshest orders ever issued by a British leader in wartime.

The Prime Minister was Winston Churchill and the battle he was referring to was the struggle to defend Singapore from an almost irresistible Japanese military juggernaut which by early 1942 was swallowing up British, American and Dutch overseas territories at a voracious pace. The exhortation from Churchill had arrived on the desk of the hapless British commander in Malaya and Singapore, Lieutenant General Arthur Percival, only two days before the final capitulation. Behind the thin line of British, Australian, Indian and Malay soldiers holding the Japanese at bay was a huge mass of Chinese, Malay and white civilians, all trying to flee Singapore by whatever means at hand, before it was too late. Families crowded the docks and quayside, fighting with army deserters to get aboard the last few remaining ships. No one wanted to fall into the hands of a terrifying Asiatic enemy whom many were comparing, in terms of brutality, to Genghis Khans Mongol hoard. Frantic mothers, their husbands already lost to the fighting, pulled along terrified and confused children towards what they prayed would be salvation and a ticket to safety. For most, they had left evacuation too late and the women and children were now trapped in a burning and battered Singapore City, the streets littered with rubble from the shelling and bombing and strewn with decomposing bodies, the air rent with the crack of bullets and the crump of mortars and artillery fire, the sky above filled with howling Japanese aircraft that swooped down to strafe at will the long columns of refugees and soldiers.

General Percivals forces had been pushed all the way down the Malay Peninsula since the initial Japanese invasion on 8 December 1941, when enemy troops had first hit beaches in southern Thailand and northern Malaya. By early February 1942 the Japanese were ashore on Singapore Island, the last significant bastion of the British Empire in Asia still resisting the Japanese. Over 70,000 British and Commonwealth troops were trapped with their backs to the sea, the Japanese literally breathing down their necks as they pushed inexorably towards the city centre. Simultaneously, the confused scenes enacted in Singapore were being replicated in almost all of the European colonies in the East. In Hong Kong, the British were also trapped with their backs against the sea, with no hope of reinforcements or relief; in the Philippines American and British nationals tried to stay one step ahead of the Japanese columns cutting through Luzon Island towards Manila; in the Netherlands East Indies, hundreds of thousands of Dutch and British civilians waited with bated breath for the next round of Japanese attacks that must surely soon strike the archipelago once Singapore had fallen; and in Burma, British families had begun to evacuate towards India, sure that the Japanese were about to cross the border and strike for Rangoon.

The maelstrom and confusion at the docks in Singapore was epic as mothers dragged small children through crowds of shouting and fighting whites and Asians, jostling the suitcases containing all they had left in the world towards ship gangplanks, while military policeman yelled at the crowds to stay back and keep order, occasionally firing warning shots into the air from their service revolvers. The deafening detonations of aerial bombs and the shriek and moan of the diving Japanese aircraft was the constant refrain of the evacuation, and the background was the huge black clouds that hung over the city as whole districts burned under the furious bombardment. The women had largely been abandoned to care for their children and get them to safety, as all the able-bodied men were at the front lines or were already dead or prisoners of the Japanese. Rich Westerners even paused to order their chauffeurs to push their expensive cars into the harbour rather than leave them for the conquerors. The clock in the tall, battle-scarred Cathay Building downtown ticked off the minutes as the British Empire in Singapore drew to a violent and ignominious close.