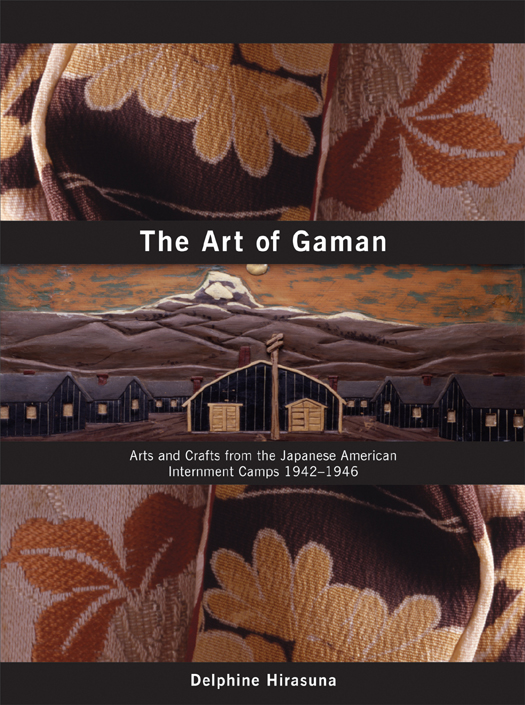

Copyright 2005 by Delphine Hirasuna

Photography 2005 by Terry Heffernan

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

www.tenspeed.com

Ten Speed Press and the Ten Speed Press colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hirasuna, Delphine, 1946

The art of gaman : arts and crafts from the Japanese American internment camps, 19421946 / Delphine Hirasuna, Kit Hinrichs; photography by Terry Heffernan.

p. cm.

Summary: A photographic collection of arts and crafts made in the Japanese American internment camps during World War II, along with a historical overview of the campsProvided by publisher. Includes bibliographical references.

1. Japanese American decorative arts. 2. Concentration camp inmates as artistsUnited States. 3. Japanese AmericansEvacuation and relocation, 19421946. I. Hinrichs, Kit. II. Title.

NK839.3.J32H57 2005

704.0869089956073dc22 2005016794

ISBN-13: 978-1-58008-689-9 (hardcover)

eBook ISBN: 978-0-307-80836-3

Jacket design by Kit Hinrichs and Takayo Muroga, Pentagram

v3.1_r1

The author discusses why beautiful objects made in the Japanese American concentration camps during World War II were often hidden away for decades.

Wartime hysteria and racism created the climate that led to the imprisonment of 120,000 Japanese Americans during World War II. Within the degrading conditions of the camps, internees struggled to create a community.

From discarded and indigenous raw materials, internees crafted an amazing variety of imaginative, graceful, and functional objects, to pass the time and to beautify their bleak surroundings.

The nightmare continued after the internees were released from the camps. To reintegrate back into communities and eke out a living, Japanese Americans rarely spoke about the camp experience.

Preface

Delphine Hirasuna

The impetus for this book began in 2000 while I was rummaging through a dust-covered wooden box that I found in my parents storage room after my mothers death. Inside, I came across a tiny wooden bird pin. From the safety-pin clasp on the back, I concluded that it must have been carved in the concentration camp where my parents were held during World War II. This prompted me to wonder what other objects made in the camps lay tossed aside and forgotten, never shown to anyone because they might generate questions too painful to answer.

The impetus for this book began in 2000 while I was rummaging through a dust-covered wooden box that I found in my parents storage room after my mothers death. Inside, I came across a tiny wooden bird pin. From the safety-pin clasp on the back, I concluded that it must have been carved in the concentration camp where my parents were held during World War II. This prompted me to wonder what other objects made in the camps lay tossed aside and forgotten, never shown to anyone because they might generate questions too painful to answer.

As a child growing up after the war, I never heard my parents and their friends discuss the camps openly, but camp came up often in passing conversations. For them, time was separated into before camp and after camp. We used to have one of those before camp. We knew them from camp. We had to buy a new one after camp. I never exactly understood, nor asked, what the camps were, but it struck me as odd that only Japanese Americans seemed to know about them. Americas concentration camps were never mentioned in textbooks nor brought up in mixed (Japanese and non-Japanese) company. Japanese Americans chose not to talk about it because it stirred a sense of shame and humiliation, the sorrow and resentment of justice denied, and fear of arousing an anti-Japanese backlash.

The postcamp years on the West Coast were harsh for Japanese Americans. For many, it meant starting over from scratch. In the farmlands of Californias San Joaquin Valley, where I was raised, I recall the weather-worn faces of the Issei (first-generation immigrantsmy grandparents generation) and how their hands were as tough as leather from laboring in the fields. Although some were said to have been rich before the war, when I knew them they were mostly tenant farmers, gardeners, and day laborers eking out barely enough to keep food on the table and a roof over their familys heads. Shikataganai. It cant be helped, they would often say, quickly adding, We have to gaman accept what is with patience and dignity. They repeated this so often, it sounded like a mantra.

Finding the bird pin among my mothers belongings made me reflect on their words. The objects that the Issei and the Nisei (second-generation, born in the United States) made in camp are a physical manifestation of the art of gaman . The things they made from scrap and found materials are testaments to their perseverance, their resourcefulness, their spirit and humanity.

In writing this book, I want to honor and preserve this aspect of the Japanese American concentration camp experience. The historical overview at the outset is presented to provide a perspective for the circumstances under which the objects were made. Without this understanding, what one sees are lovely objects, folk art, Americana with a Japanese twist. But all these lovely objects were made by prisoners in concentration camps, surrounded by barbed wire fences, guarded by soldiers in watchtowers, with guns pointing down at them.

The objects shown here are only a small sampling of the things that were created in the camps. The wall murals and gardens are long gone. I could not locate examples of some popular camp art forms such as miniature tray landscapes ( bon-kei ). Judging by the number of people who lent me things still packed in boxes from 1945, countless other objects are undoubtedly hidden in garages.

Many people contributed to making this book happen, but I owe a special thank-you to my aunt and uncle, Bob and Rose Sasaki, who championed this project as if it was their own. And, of course, I wish to single out my dear friends designer Kit Hinrichs and photographer Terry Heffernan, who volunteered their incomparable talents to help bring this book to reality.

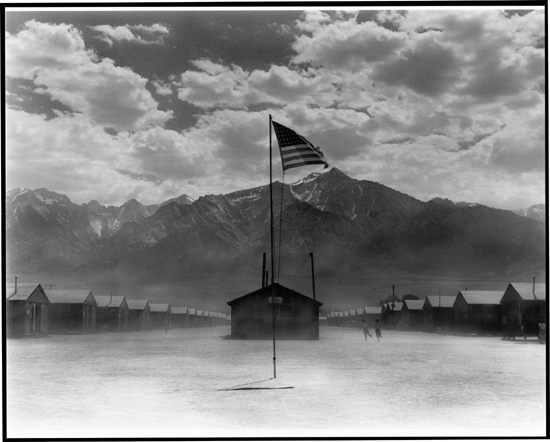

DUST STORM AT MANZANAR WAR RELOCATION AUTHORITY CENTER, DOROTHEA LANGE

The Camps

The Camps in Context

The impetus for this book began in 2000 while I was rummaging through a dust-covered wooden box that I found in my parents storage room after my mothers death. Inside, I came across a tiny wooden bird pin. From the safety-pin clasp on the back, I concluded that it must have been carved in the concentration camp where my parents were held during World War II. This prompted me to wonder what other objects made in the camps lay tossed aside and forgotten, never shown to anyone because they might generate questions too painful to answer.

The impetus for this book began in 2000 while I was rummaging through a dust-covered wooden box that I found in my parents storage room after my mothers death. Inside, I came across a tiny wooden bird pin. From the safety-pin clasp on the back, I concluded that it must have been carved in the concentration camp where my parents were held during World War II. This prompted me to wonder what other objects made in the camps lay tossed aside and forgotten, never shown to anyone because they might generate questions too painful to answer.