ALSO BY BRUCE HENDERSON

Sons and Soldiers

Rescue at Los Baos

Hero Found

Down to the Sea

Fatal North

True North

Trace Evidence

Time Traveler (with Dr. Ronald L. Mallett)

And the Sea Will Tell (with Vincent Bugliosi)

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2022 by Bruce Henderson. Afterword copyright 2022 by Gerald Yamada. All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Henderson, Bruce B., [date] author.

Title: Bridge to the sun: the secret role of the Japanese Americans who fought in the Pacific in World War II / Bruce Henderson.

Description: First edition. | New York: Alfred A. Knopf, [2022] |

Identifiers: LCCN 2021053217 (print) | LCCN 2021053218 (ebook) | ISBN 9780525655817 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780525655824 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: World War, 19391945Participation, Japanese American. | Japanese American soldiersHistory20th century. | Japanese American soldiersBiography. | World War, 19391945Japanese Americans. | World War, 19391945CampaignsPacific Area.

Classification: LCC D769.8.A6 H46 2022 (print) | LCC D769.8.A6 (ebook) | DDC 940.53089/956073dc23/eng/20220107

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021053217

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021053218

Ebook ISBN9780525655824

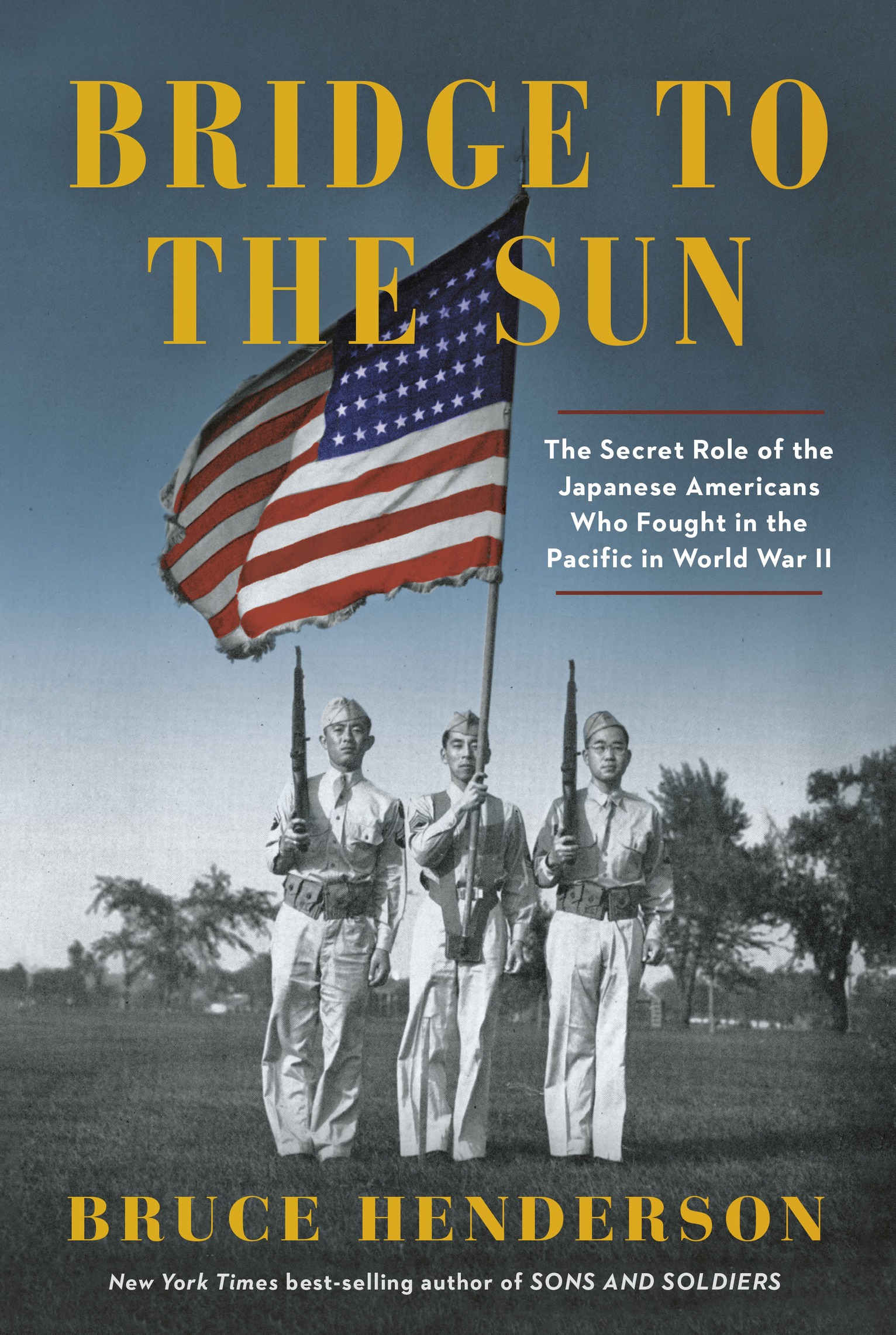

Cover photograph: U.S. Army Signal Corps

Cover design by Jenny Carrow

ep_prh_6.0_141032870_c0_r0

For them all

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Bridge to the Sun tells the little-known story of the U.S. Armys Japanese American soldiers who fought in the Pacific theater during World War II, and their decisive role in the defeat of Japan. Thousands of Niseifirst-generation American citizens born in the United States whose parents were immigrants from Japanserved as interpreters, translators, and interrogators throughout the Pacific, participating in all the major battles. Guadalcanal. New Guinea. Solomons. Iwo Jima. Burma. Leyte. Okinawa. Tantamount to a secret weapon in the war against Japan, they were intent on proving their loyalty even as their families were being held in internment camps. They fought two wars simultaneously: one, against their ancestral homeland; the other, against racial prejudice at home.

After Americas declaration of war against Japan following the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese immigrants (Issei) living in the U.S. were branded as enemy aliens. Their Nisei offspring were seen by many Americans not as fellow countrymen but as the face of the hated enemy. It was unsafe for them to walk down the streets of some U.S. communities. As a result of this nations failure to correctly gauge their loyalty and patriotism, coupled with the widespread xenophobia regarding anyone and anything Japanese, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 in February 1942 that authorized the removal of some 110,000 men, women, and children of Japanese ancestry from four western states to hastily built camps run by the War Relocation Authority. An estimated two-thirds of them were U.S. citizens. Stripped of their constitutional rights, they were rounded up and forced into internment camps.

In a few short months, the War Department, desperate to find sufficient numbers of Japanese speakers to serve in the Military Intelligence Service (MIS) in the Pacific, concluded that training the Nisei for this vital role might be the answer. But there was a key question to be addressed: Would Japanese Americans be willing to fight against their ancestral homeland? The Army sent recruiters to relocation camps to find out. In one camp after another, the irony was inescapable to the internees. They were being kept behind barbed-wire fences because the U.S. government questioned their loyalty, and now the Army needed them to volunteer in the war against Japan, the very country they were suspected of being sympathetic toward? Even the most patriotic Nisei harbored strong feelings that their rights as U.S. citizens had been violated. And yet, from their bleak, barracks-like quarters inside guarded compounds in desolate locations, waves of young Japanese Americans answered their nations call. Implored one tearful mother to her departing nineteen-year-old son as he left to join the Army: Make us proud.

In 1942, the first Nisei recruited by the U.S. Army for the newly opened Military Intelligence Service Language School (MISLS) arrived at Camp Savage, Minnesota. Initial plans called for a new class to graduate every year, but the pressure to have Japanese-speaking MIS teams in the field resulted in a compressed timetable, with graduation in half that time. The War Department ordered the school to supply enough Japanese-language teams to support every division fighting in the Pacific. As a result, each succeeding class was larger than the one before it, with the curriculum ever more focused and specialized. By spring 1946, the MISLS had produced nearly six thousand graduates.

The war planners in Japan believed their language so complex that few Westerners would fully understand it. As a result, many Japanese military communications were sent in the open without being coded. Trained Nisei linguists in the field were able to rapidly translate these messages and other captured documents and provide U.S. commanders with timely intelligence about enemy defenses and plans, the condition and morale of its troops, and technical specifications of their weapons, all of which were put to use in winning battles and saving American lives.

The story of the Japanese American soldiers who served in the Pacific theater is one of action, pride, courage, and sacrifice. That U.S. combat units fighting throughout the Pacific had the ability to understand the enemys language and read their communications was among the best kept secrets of the war. In the decades that followed, a veil of secrecy stayed in place over matters pertaining to military intelligence. Even when the World War II records started to be declassified decades later, much of this story remained untouched in dusty storage bins at national archives. The buried and scattered records of their service were often incomplete or not easily found. The fact that their small intelligence teams were attached to larger units made finding detailed accounts of their wartime activities all the more challenging. Astonishingly, no roster of the Japanese American soldiers who served in the Pacific was ever compiled by the Army. (See Appendix for the first list of more than three thousand Nisei veterans of the Pacific war.)

For decades, there were no reunions of the MIS Nisei; they had gone through the war without having much contact with others like themselves except for the few men on their own team. After the war, they were disinclined to join veterans organizations, as their race and ancestry made them unwelcome in the usual circles of military fraternal groups. Some local posts of the Veterans of Foreign Wars prohibited Japanese Americans from joining. Many Nisei veterans, satisfied with having done their duty and proven their loyalty to America, did not speak openly of their wartime experiences for years, even to their families.