Published in 2017 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC

243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016

Copyright 2017 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC

First Edition

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwisewithout the prior permission of the copyright owner. Request for permission should be addressed to Permissions, Cavendish Square Publishing, 243 5th Avenue,

Suite 136, New York, NY 10016. Tel (877) 980-4450; fax (877) 980-4454.

Website: cavendishsq.com

This publication represents the opinions and views of the author based on his or her personal experience, knowledge, and research. The information in this book serves as a general guide only. The author and publisher have used their best efforts in preparing this book and disclaim liability rising directly or indirectly from the use and application of this book.

CPSIA Compliance Information: Batch #CW17CSQ

All websites were available and accurate when this book was sent to press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bjorklund, Ruth, author.

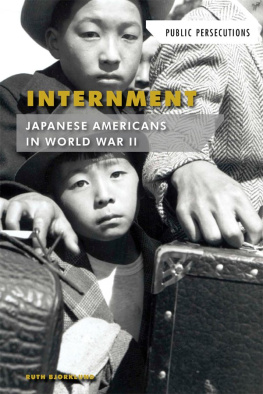

Title: Internment : Japanese Americans in World War II / Ruth Bjorklund.

Description: New York : Cavendish Square Publishing, [2017] | Series: Public persecutions | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016026819 (print) | LCCN 2016031733 (ebook) | ISBN 9781502623232 (library bound) | ISBN 9781502623249 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Japanese Americans--Evacuation and relocation, 1942-1945--Juvenile literature. | World War, 1939-1945--Japanese Americans--Juvenile literature.

Classification: LCC D769.8.A6 B574 2017 (print) | LCC D769.8.A6 (ebook) | DDC 940.53/1773089956--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016026819

Editorial Director: David McNamara

Editor: Fletcher Doyle

Copy Editor: Nathan Heidelberger

Associate Art Director: Amy Greenan

Designer: Stephanie Flecha

Production Coordinator: Karol Szymczuk

The photographs in this book are used by permission and through the courtesy of:

Cover Dorothea Lange/Education Images/UIG/Getty Images; pp. 4, 11 Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone/ Getty Images; pp. 7, 8, 46, 51, 69, 75, 99 Bettmann/Getty Images; p. 17 North Wind Picture Archives; p. 21 Buyenlarge/Getty Images; p. 24 Museum of History and Industry; p. 27 Bain News Service/Library of Congress; p. 29 Dave Buresh/The Denver Post/Getty Images; pp. 34, 60 Popperfoto/Getty Images; p. 37 Buyenlarge Archive/UIG/Bridgeman Images; p. 39 ullstein bild/Getty Images; p. 43 Library of Congress; p. 56 NY Daily News Archive/Getty Images; p. 63 U.S. Army Signal Corps photo/Library of Congress/ Corbis/VCG/Getty Images; p. 72 Clem Albers/Library of Congress; p. 79 Dorothea Lange/Everett Historical/Shutterstock; p. 88 nsf/Alamy Stock Photo; p. 92 Rondal Partridge/FSA/Library of Congress/ File:Dorothea Lange atop automobile in California.jpg/Wikimedia Commons; p. 97 Harris & Ewing/Library of Congress; p. 100 AP Images; p. 105 Paul Kitagaki Jr./Sacramento Bee/MCT/Getty Images; p. 109 Mark Kauffman/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty Images; p. 111 Robyn Beck/AFP/Getty Images; p. 112 Joe Mabel/File:Bainbridge Island Japanese American Exclusion Memorial 19.jpg/Wikimedia Commons.

Printed in the United States of America

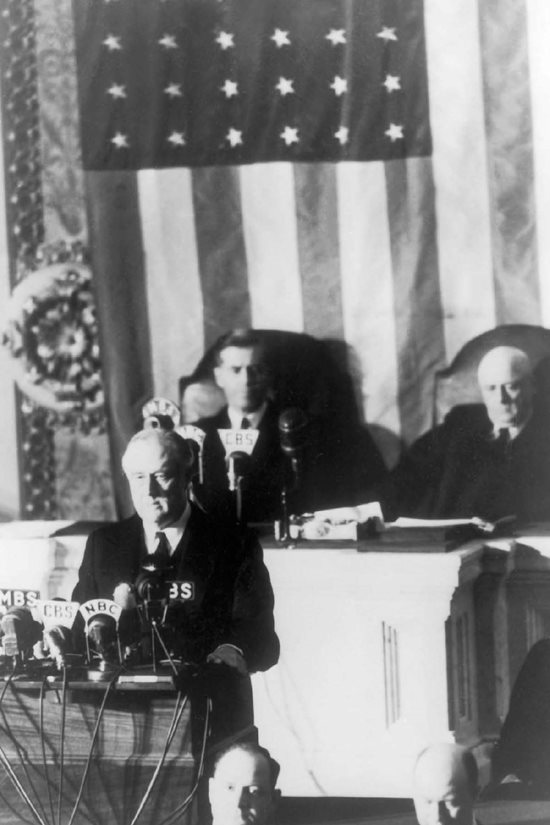

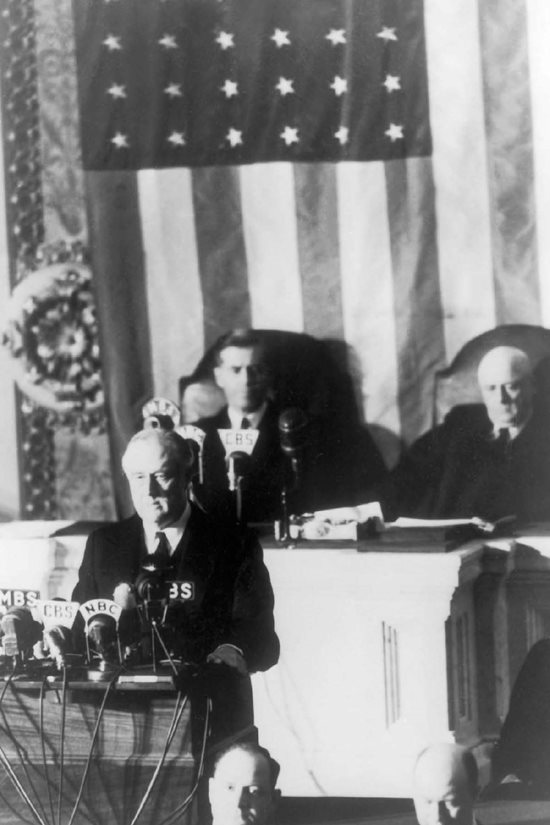

President Franklin D. Roosevelt addresses Congress and the nation, announcing the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

INTRODUCTION

Rapid Backlash

T hey were marked as different from other races and were not treated on an equal basis, wrote humanitarian Eleanor Roosevelt, wife of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. In a 1943 magazine article, she described the racial prejudice and forced evacuation being endured by Japanese Americans during World War II. In one part of our country they were feared as competitors, and the rest of our country knew them so little and cared so little about them that they did not even think about the principle that we in this country believe inthat of equal rights for all human beings. As the First Lady stated, the Bill of Rights assures equal rights for all, yet in 1941, most people in the country, including her husband, ignored the Constitution and turned their backs on Japanese Americans.

On December 7, 1941, Japanese bombers executed a deadly and unprovoked surprise attack on US naval ships anchored in Pearl Harbor, on the island of Oahu in Hawaii. The next day, President Roosevelt stood before Congress to request a declaration of war. His statements were brief. America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan ... Hostilities exist. There is no blinking at the fact that our people, our territory, and our interests are in grave danger. His request could barely be heard above the thunderous roar of approving members of Congress.

As Congress declared war on Japan on December 8, 1941, the United States made its entry into World War II. Americans were immediately enveloped in fear. As people girded for war, most regarded Japanese Americans, including those that had become US citizens, as enemy aliens.

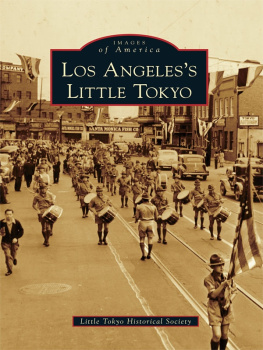

After the attack, the full force of decades of anti-Japanese prejudice exploded. Derogatory remarks and bigoted epithets were used in everyday conversation as well as in public. Newspapers ran headlines denouncing Japs or Nips, a term derived from Nippon , the name by which the Japanese people call their country. The airwaves shrieked with dread over the threat of the Yellow Peril.

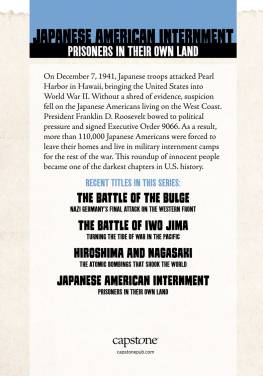

When the government issued an internment order, resulting in more than 120,000 Japanese Americans being relocated to concentration camps in remote, desolate parts of the American West, few non-Japanese Americans protested. The mass incarceration of American citizens and legal residents based solely upon their Japanese ancestry was rarely deemed unlawful. The United States military never had to prove that the Japanese Americans posed a military threat or that internment would make the nation safer from attack.

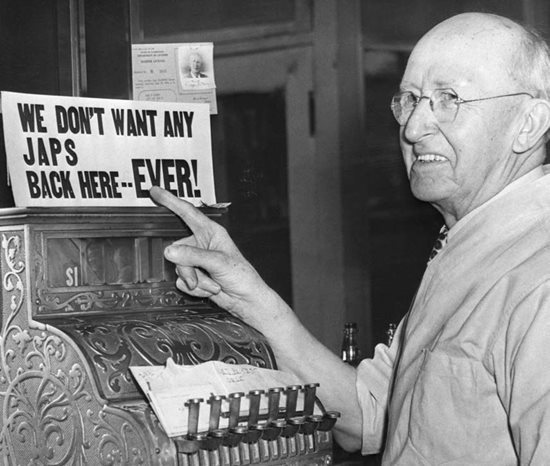

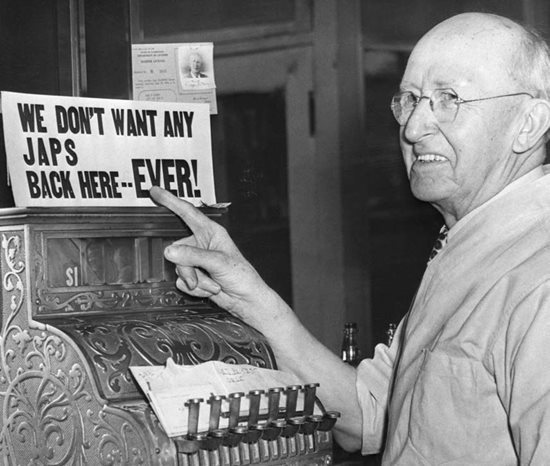

From big cities to small towns, anti-Japanese sentiment was rampant throughout the western United States.

By and large, most Japanese Americans peacefully accepted their fate. There were few resistors or protestors, although confusion and uncertainty overwhelmed them. Most Japanese Americans believed that American ideals and values would not be abandoned and held the belief that the alarming situation was temporary. This proved incorrect. On April 30, 1942, Japanese Americans were given a week to gather personal items and dispense with the rest of their belongings. Not until March 1946 were the last of the imprisoned Japanese Americans released from the internment camps.

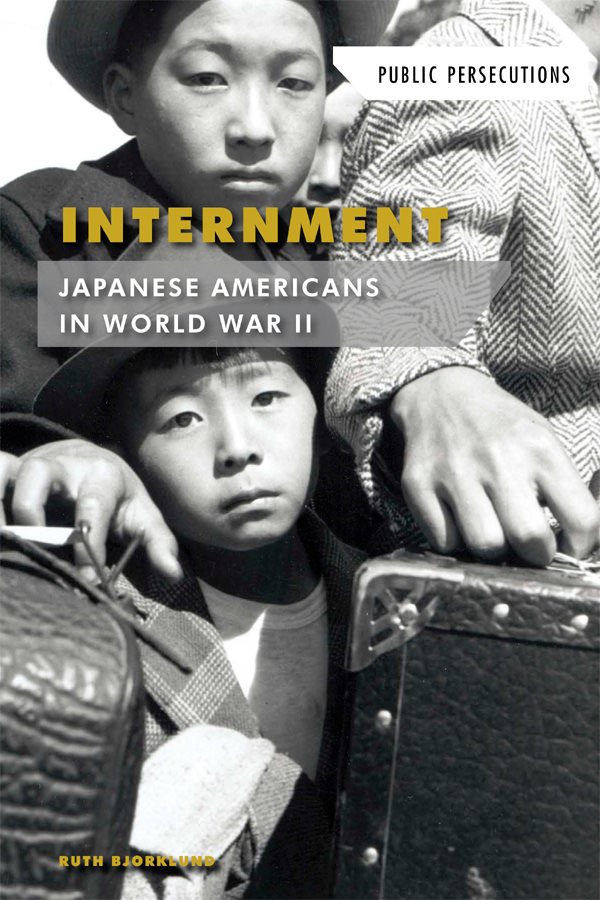

Young Japanese picture brides arrive in the United States to marry Japanese men they have never met.

ONE

The Ancient and the New