FOREWORD

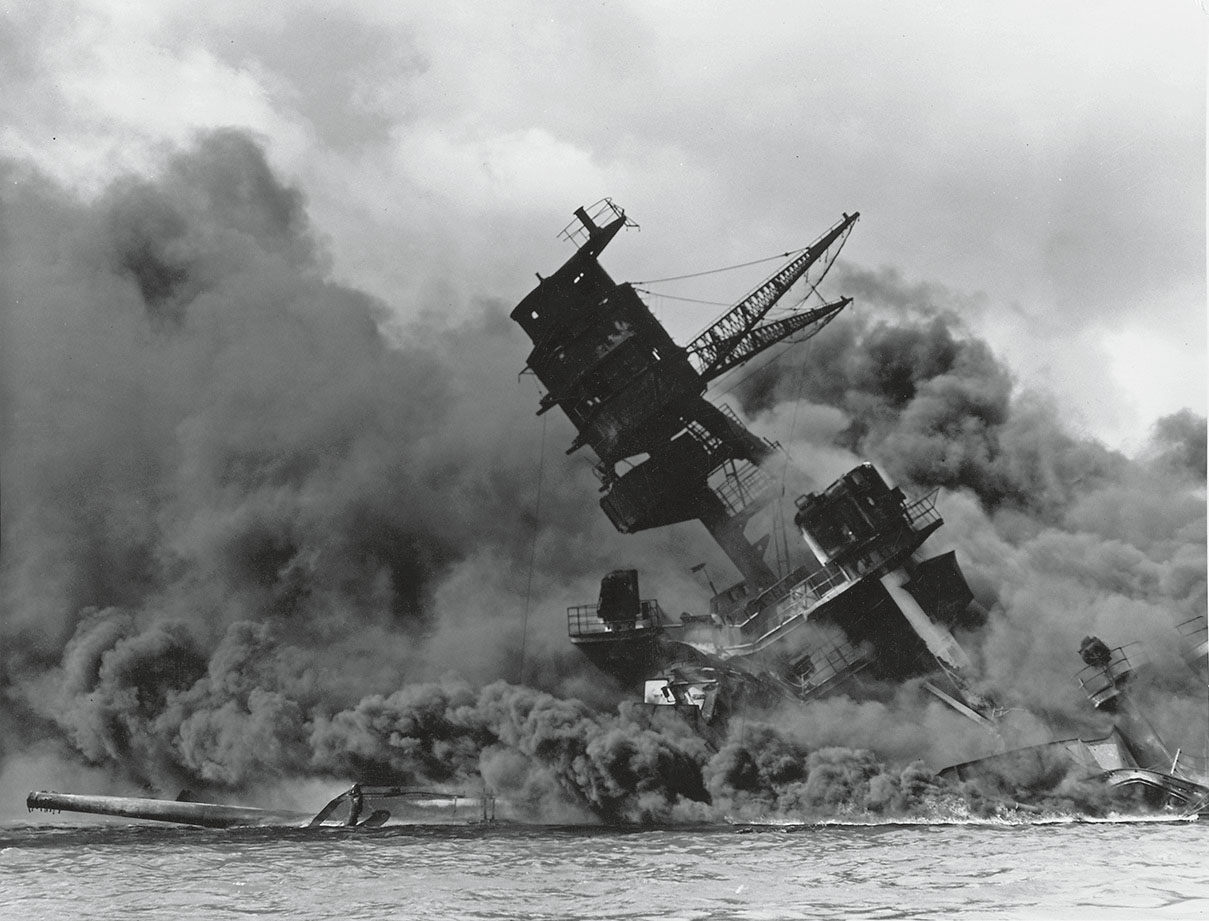

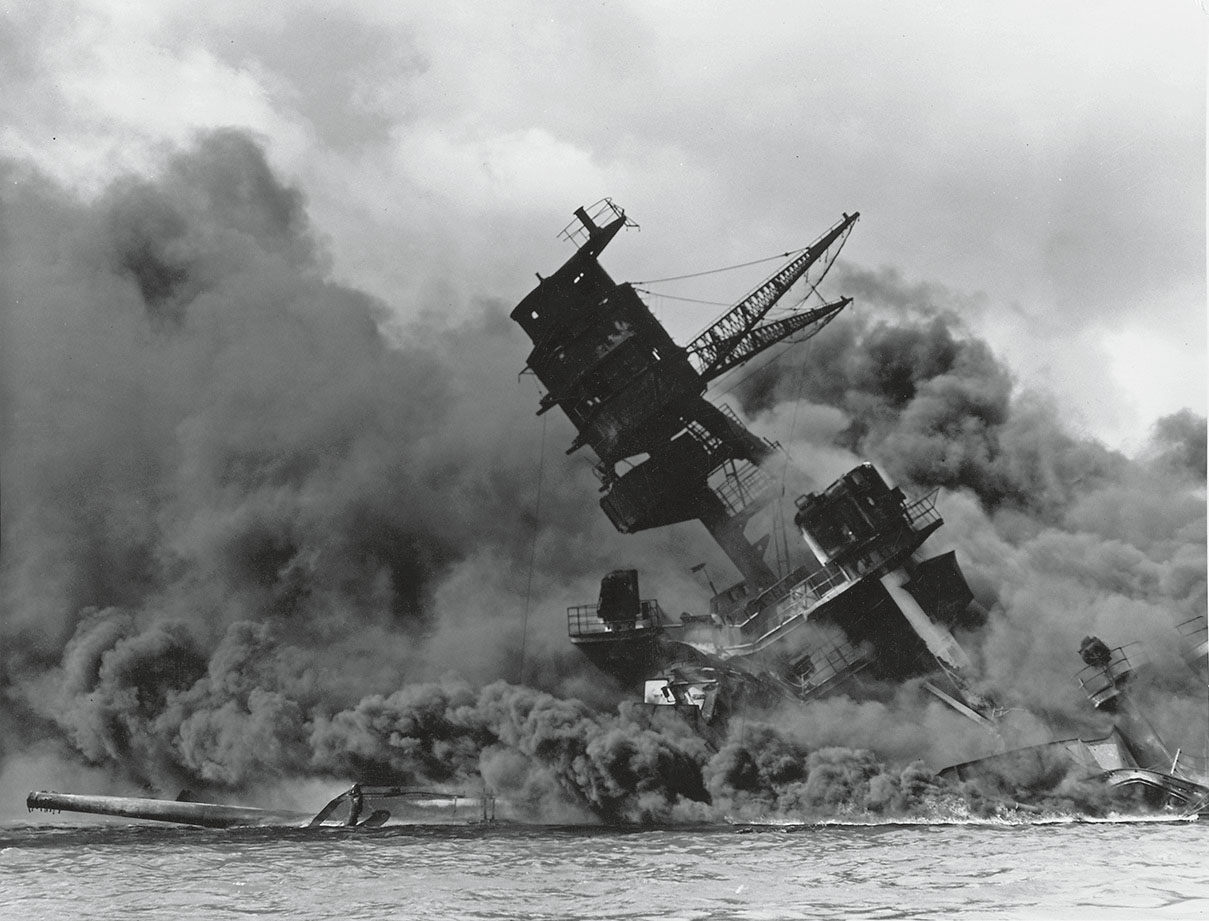

More than 1,170 crewmen were killed when the Japanese attacked and sank the USS Arizona .

The United States had managed to stay out of the world war that engulfed Europe in September 1939 with Germanys invasion of Poland. The U.S. had also resisted getting involved in Japans aggression in Asia, where it had entered into a full-scale war against China in 1937. That changed on a sunny morning in early December 1941. That day, December 7, the Japanese launched a surprise attack on the U.S. naval base at Hawaiis Pearl Harbor. Some 2,403 Americans, including 68 civilians, were killed, six battleships were damaged, and two were destroyed.

The next day the United States declared war on Japan and three days later declared war on its Axis power partners, Germany and Italy. Many Americans felt they were in imminent danger of another attack. If the Japanese could destroy Pearl Harbor, what was to stop them from launching a follow-up attack on the West Coast of the United States? Suspicions turned to Japanese Americans, who made up 1 percent of the population of California, more than 93,000 people. Could they be aiding the enemy by spying, sabotaging American industry, or committing other treasonous acts? With not a shred of evidence of this, the U.S. government let fear drive it to act on its worst impulses.

The U.S. government immediately imposed restrictions on Japanese Americans. They ordered the closing of Japanese language schools. Japanese Americans on the West Coast owning shortwave radios and cameras had to turn them in to the government. Then on , and the majority of them were not naturalized U.S. citizens. Because they retained much of their Japanese traditions in terms of language and culture, they were the first to be suspected of aiding the enemy.

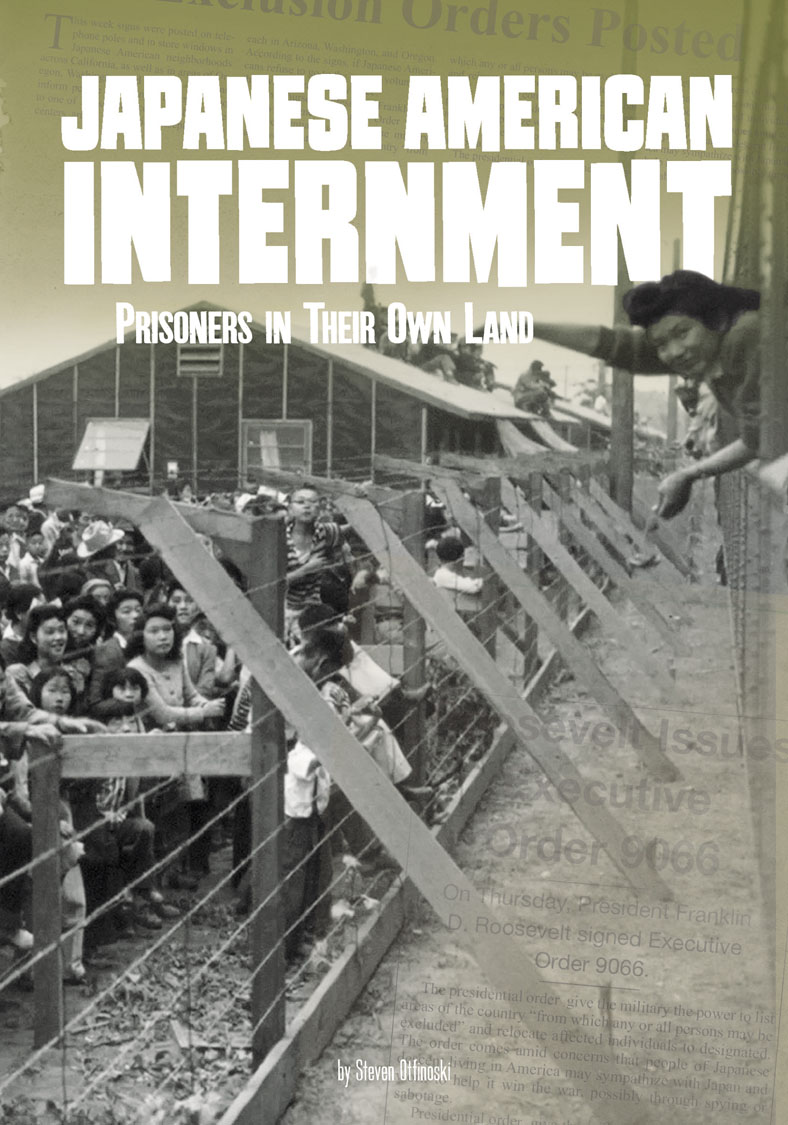

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19. The order authorized the War Department to officially establish these military areas or zones from which any or all suspicious people would be removed. By March 2 the First Zone was designated to include the western parts of California, Washington State, Oregon, and southern Arizona. Zone 2 included the remaining parts of these four states. Later that month, the first large group of Japanese Americans including many familieswere forced to leave their homes. They were sent to Manzanar War Relocation Center in eastern California. By September Manzanar housed more than 10,000 Japanese Americans. More than 110,000 other Japanese Americans were sent to nine other . This roundup of innocent people would become one of the darkest chapters in American history.

Manzanar was the first of 10 internment camps for Japanese Americans.

The attack on Pearl Harbor brought the United States into World War II and cast suspicion on blameless Japanese Americans.

Susumu Satow

Sacramento, California, December 7, 1941, noon

Eighteen-year-old Susumu Satow was playing catch with his father when the news came over the radio. The American naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii had been bombed by the Japanese in a surprise attack.

Susumu, known as Sus to family and friends, couldnt believe it. As a Japanese American he felt terribleboth for his country and his family.

What is going to happen to us? he asked his father.

Mr. Satow shook his head, a troubled look on his face. It is not going to be good, he said.

Sus wasnt sure what his father meant, but he knew that he was usually right.

Mine Okubo

Berkeley, California, December 7, 1941, 12:05 p.m.

Mine Okubo was eating a late breakfast in her kitchen when she heard the news on the radio. The Pearl Harbor attack was shocking, but she didnt think it would affect her or her brother much. Her brother, Toku, was a student at the University of California at Berkeley, where Okubo had received two fine arts degrees. Now age 29, Okubo was a professional artist working for the Federal Arts Project. For two years she had been creating mural projects for Fort Ord and the Servicemens Hospitality House in nearby Oakland. She was proud to be an American and was using her creativity to give back to her country. No one could accuse her of being a Japanese sympathizer. What did she have to fear?

Isamu Noguchi

On the road to San Diego, California, December 7, 1941, 12:10 p.m.

Isamu Noguchi sat back and enjoyed the warm California sunshine as he drove his car down the roadway. A well-known sculptor at age 37, he was heading to San Diego to look at some stone for his possible and see what he could do to help the United States in this new conflict with Japan.

Isamu Noguchi had his first sculpture exhibit in 1924, when he was still a college student. This sculpture, Paphnutius , was part of the exhibit.

Masao Itano

The jail at Sacramento, February 17, 1942, 2:00 p.m.

Masao Itano knew he had done nothing wrong. But with the hysteria in the country since the Pearl Harbor attack, that didnt seem to matter. The United States was now at war with Japan and its Axis partners in Europe, Germany, and Italy. Almost daily, it seemed more and more restrictions were put on Japanese Americans. Just a few weeks before, the attorney general had set up strategic military areas on the West Coast from which suspected aliens would be removed. Itano did not see himself as an alien. He had come to the U.S. at age 17 from Japan to go to college, start a new life, and raise a family. Nevertheless, the previous day Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agents had come to his house and arrested him on suspicion of being an enemy alien. It was all a terrible mistake, Itano thought. Then police officers told him they were transporting him to another jail but wouldnt tell him where.

As Itano was led out by the officers, a crowd stood watching. He felt nothing but shame at being seen in handcuffs like a common criminal. Then suddenly he spotted his wife, Sumako, in the crowd. She waved to him. But his only thoughts now were for his son, Harvey, who was soon to graduate from college. Tell Harvey to continue to study, he yelled to her.

I already did, she called back. And before he could say another word to his wife, the officers hustled him into a police car and drove off.

Susumu Satow

Sacramento, California, February 20, 1942, 2:30 p.m.

Suss father was right when he said things would turn bad for them after Pearl Harbor. At school, classmates that Sus used to be friendly with now looked at him with cold stares. As he walked home from school he passed handwritten signs that read JAPS MUST GO. They were talking about him! An American! Why, hed rather play baseball than go to Japanese language school! Only the day before, President Roosevelt had signed the order that singled out Japanese Americans living in what was now called a war zone.