CHAPTER ONE

PRISONERS IN THEIR OWN COUNTRY

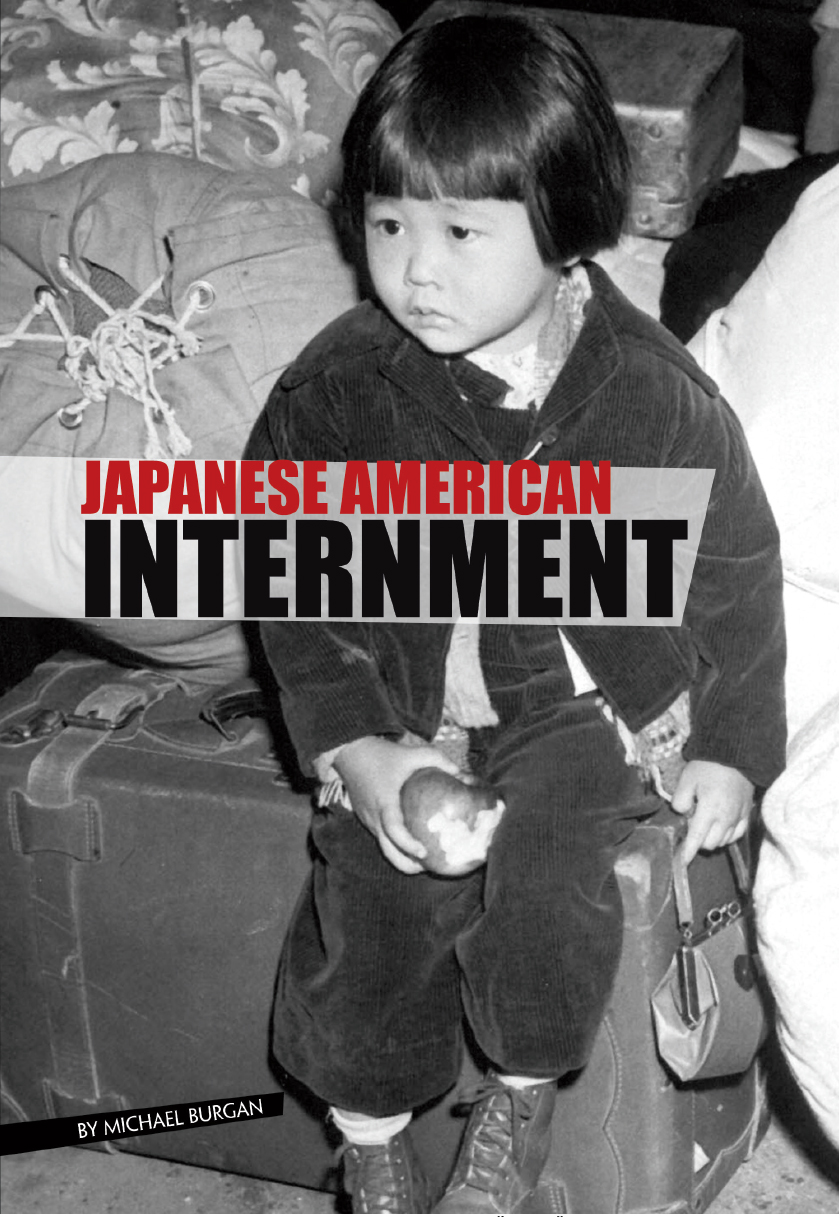

It was December 7, 1941. Seven-year-old Jeanne Wakatsuki waved as she watched her fathers fishing boat sail away from the wharf in Long Beach, California. Her father, Ko, and older brothers, Woody and Bill, were heading out to catch the sardines that they sold to the local canneries.

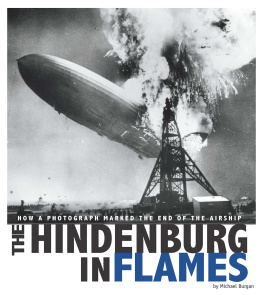

The USS California was just one of the many U.S. battleships damaged or destroyed by the Japanese during the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The Wakatsuki familys boat, along with about 25 others sailing out that day, wasnt expected to return for several days or even weeks, depending on how well the fishing went. That day, however, the boats turned around almost immediately and returned to the wharf. Jeanne and her family soon learned why. That morning Japanese planes and submarines had attacked the Pearl Harbor Naval Base in Hawaii, killing more than 2,400 Americans. The United States declared war on Japan the next day, joining the many other countries that were fighting World War II.

Ko Wakatsuki had immigrated to Hawaii from Japan in 1904 at age 17 and later settled in California. He and his wife, Riku, had 10 children, all of whom were born in the United States and were American citizens. But U.S. laws prevented Japanese immigrants such as Ko and Riku from becoming American citizens.

Immediately after the Pearl Harbor attack, many Japanese immigrants were questioned about their loyalty to the United States. Some were arrested and accused of providing aid to Japan. Ko was one of them. He was charged with delivering oil to Japanese submarinesa charge he deniedand was sent to a mens prison camp at Fort Lincoln in Bismarck, North Dakota.

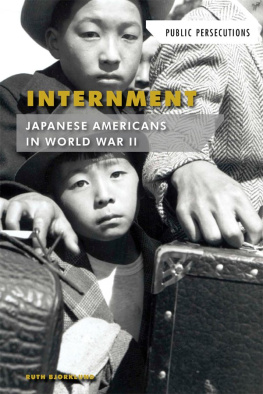

Riku, her mother, and her four children still living at home left their home in Ocean Park, California. They first moved into her son Woodys home in Terminal Island and then to Los Angeles. They were living there on February 19, 1942, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. The order allowed the government to round up people of Japanese descent who were living on the West Coast and send them to what were called relocation camps. Many Americans were worried that the Japanese Americans would sympathize with Japan and work to help it win the war, possibly by spying for Japan or sabotaging American factories and military operations.

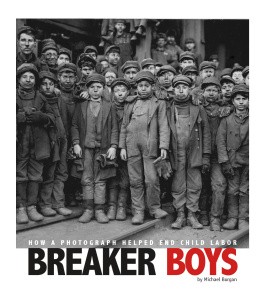

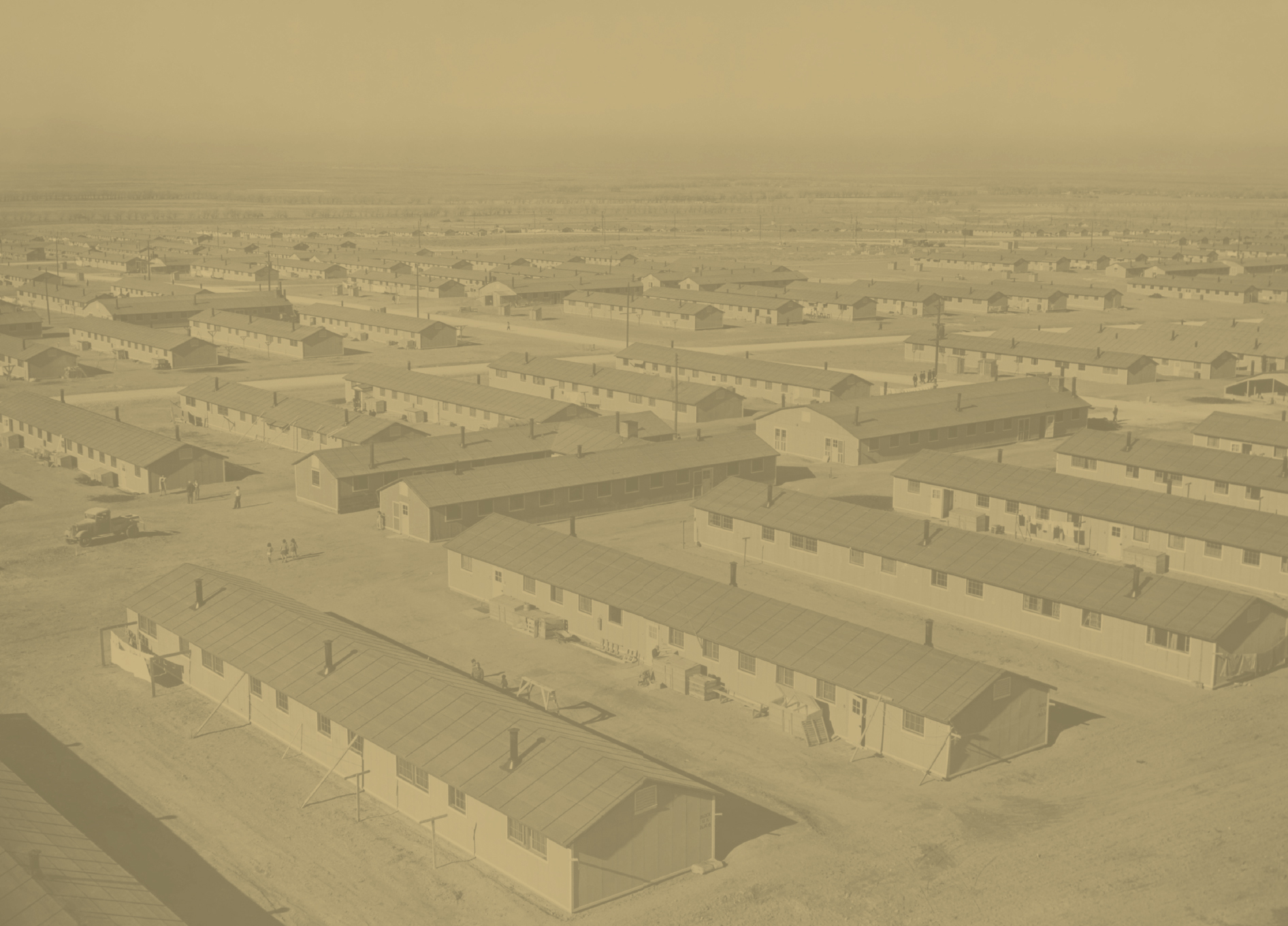

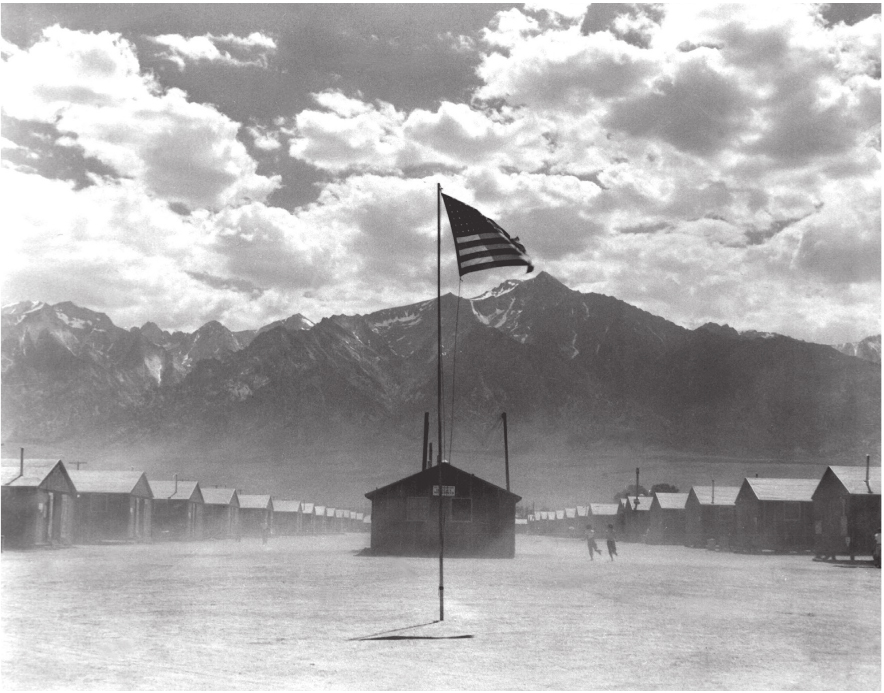

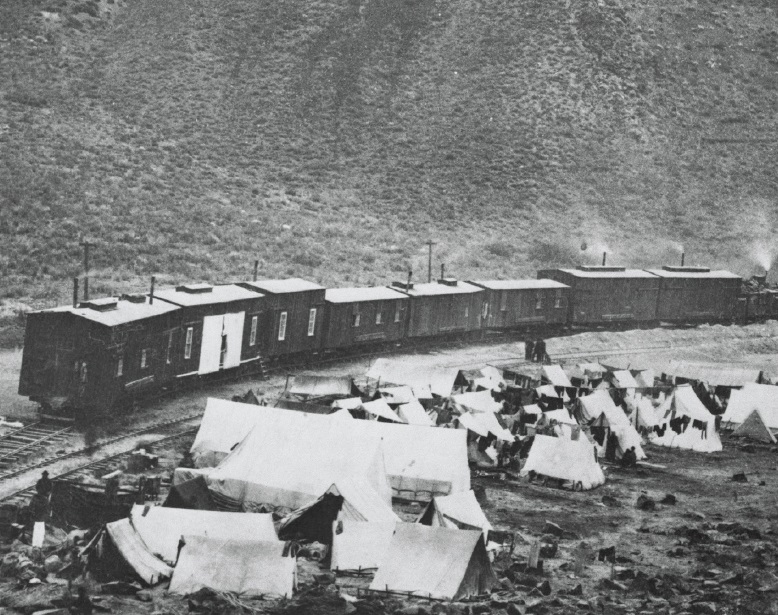

More than 10,000 Japanese Americans were crowded into 504 barracks at Manzanar War Relocation Center.

In March 1942, Jeanne and her mother, grandmother, four brothers, two sisters, two sisters-in-law, and a baby niece boarded a bus in Los Angeles. They traveled all day until reaching Owens Valley near the Nevada border. It was a dusty, barren area consisting of hastily built wooden barracks surrounded by barbed wire and guard towers. Its name was Manzanar War Relocation Center, and it was one of 10 camps that housed Japanese Americans during World War II.

JAPANESE AMERICANS

During World War II, people of Japanese ancestry were classified according to how long they had lived in the United States. Those who were born in Japan were called Issei. Their children who were born in the United States were called Nisei. Most Nisei were born before World War II. The grandchildren of the Issei, known as the Sansei, were mostly born during or after World War II. Some Japanese Americans born in the United States went to Japan for school and then returned to the United States. They were called Kibei.

Jeanne and her familyher father joined them after nine months in the prison campspent the next three years at the camp. They were not allowed to leave even though they had done nothing wrong. They were among nearly 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry who were imprisoned during World War II. More than half of them were American citizens.

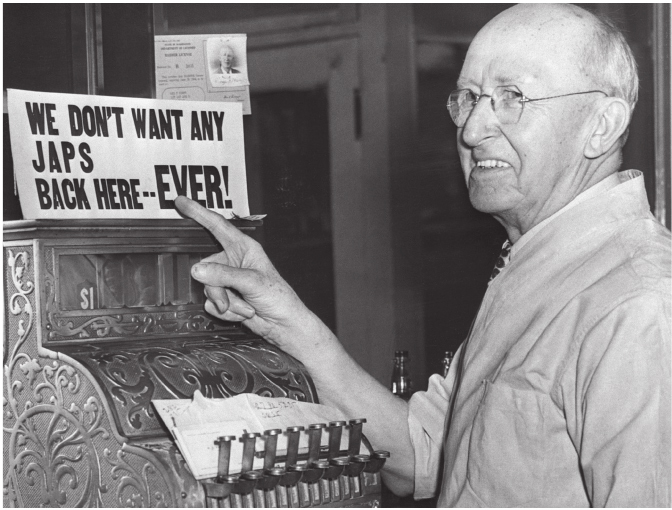

Many Americans who supported the internment genuinely feared a Japanese invasion of the United States, either in Hawaii or on the West Coast of the United States. At the time most people of Japanese ancestry lived in the western United States, with the largest concentration in California, Oregon, and Washington. Some U.S. leaders worried that people of Japanese ancestryeven those who were U.S. citizenswould be disloyal to the United States. They believed that sending Japanese Americans to the camps, where their actions could be watched and limited, was needed to protect national security.

The bombing of Pearl Harbor only fueled racism and prejudice against the Japanese. Anti-Japanese signs were a common sight after the attack.

the Japanese did.

The last Japanese Americans left the camps in 1946, more than six months after World War II ended. The years in the camps changed their lives forever. They also raised questions about the actions a nation should take during wartimequestions still debated today.

CHAPTER TWO

JAPANESE IMMIGRATION

The Japanese werent the first Asian people to immigrate to the United States. Beginning in 1850, many Chinese men came to the United States to work in California gold mines. When the Gold Rush ended, many of them stayed in the United States. They were willing to perform dangerous jobs and work for lower wages than American citizens expected. In the 1860s Chinese workers played an important part in completing the transcontinental railroad between Omaha, Nebraska, and Sacramento, California. They also worked in laundries, on farms, and as servants. Some saved enough money to establish their own businesses and bring their families to the United States.

About 10,000 Chinese workers were brought in to work on the transcontinental railroad. They lived in makeshift camps right along the railroad.

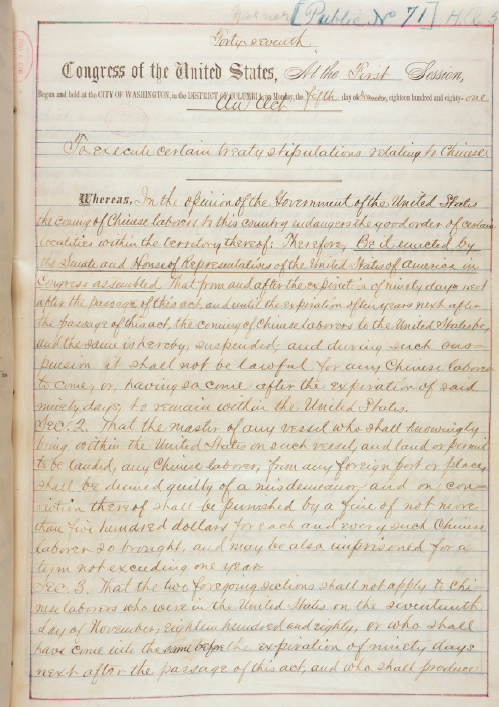

In the 1870s, though, the United States had an economic slowdown. There was more competition for the fewer jobs that were available, and many Americans began to resent the Chinese immigrants because they would work for less. Congress in 1882 passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which prohibited immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years. It was the first U.S. law designed to keep immigrants out of a country. The Geary Act in 1892 extended the immigration ban for another 10 years.

The Chinese Exclusion Act was approved on May 6, 1882.

Japans leaders had closed their country to trade with western nations and visitors from them about 1600. Japan remained isolated from the West until 1853, when U.S. Navy Commodore Matthew C. Perry traveled to Japan. On his second visit in 1854, Perry negotiated a treaty that allowed trade between Japan and the United States. This relationship eventually speeded immigration of Japanese people to the West. American businessman Eugene Van Reed brought about 200 Japanese people to the South Pacific islands of Hawaii and Guam in 1868 to work on sugarcane plantations there. Hawaii was then an independent kingdom, and Guam was a Spanish colony. Both islands became U.S. territories in 1898.