[ A TRAGEDY OF DEMOCRACY ]

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

PUBLISHERS SINCE 1893

NEW YORK CHICHESTER, WEST SUSSEX

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2009 Greg Robinson

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-52012-6

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Robinson, Greg, 1966

A tragedy of democracy : Japanese confinement in North America / Greg Robinson.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-12922-0 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-52012-6 (e-book)

1. Japanese AmericansEvacuation and relocation, 19421945. 2. Japanese AmericansPacific StatesSocial conditions20th century. 3. Japanese AmericansGovernment policyHistory20th century. 4. Pacific StatesRace relationsHistory20th century. 5. United StatesRace relationsHistory20th century. 6. World War, 19391945social aspectsUnited States. 7. JapaneseGovernment policyCanadaHistory20th century. 8. CanadaRace relationsHistory20th century. 9. World War, 19391945Social aspectsCanada. I. Title.

D796.8.A6R64 2009

940.531773dc22

2008049150

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

References to Internet Web sites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

ALTHOUGH THE MOST COMMONLY USED TERM FOR THE WARTIME experience of Japanese Americans is internment, I have chosen not to use that term. Internment properly refers to the detention of enemy nationals by a government during wartime. The United States government, as noted in this book, did intern enemy aliens during the war, in camps run by the Justice Department. In contrast, the vast majority of those of Japanese ancestry who were summarily uprooted, moved, and held by the U.S. government during World War II were American citizens. The fact that there is no commonly understood term to describe such an action with precision hints at how unprecedented the governments policy was. The official language used was of evacuation and relocation. However, the government officials who evolved those terms were clearly less concerned with finding exact language than with inventing euphemisms to make their policy seem more acceptable. Perhaps the most precise equivalent, in legal terms, would be commitment, in the sense of being held involuntarily in an institution, but this definition hardly explains the treatment of Japanese Americans. Instead, I use the phrase removal, as in the expulsion of the Cherokee and other Native Americans from the American South during the 1830s, to describe the internal exile of ethnic Japanese, and confinement for their experience once removed. Various historians and activists have called the policy incarceration. Yet incarceration is a fancier synonym for imprisonment: these institutions were not penitentiaries. I thus make use of the more inclusive word confinement. I do use internment at times when speaking of Canada, where the legal status of aliens and citizens was more fluid.

An even more vexed question, and one that has stirred up considerable controversy in the decades since the war, is what to call the camps in which the Japanese Americans were confined, and those who were placed there. President Roosevelt publicly referred to the camps as concentration camps on two occasions, as did other government officials. Nevertheless, the official term developed by the army and the War Relocation Authority was relocation centers or reception centers. The holding areas on the West Coast became assembly centers in officialese. Many Japanese Americans and other activists and scholars insist on the phrase concentration camp, in keeping with the pre-Holocaust definition of the phrase as a settlement where masses of people are concentrated. I have no quarrel with such a practice, but because of the inextricable association of the words concentration camp with the Nazi death camps, I have chosen to avoid it and simply use the word camp, which I think suffices to describe the areas where the Japanese Americans were confined. Rather then the official word resident, I choose to use the word inmate as the most precise description of the status of Japanese Americans involuntarily placed in confinement.

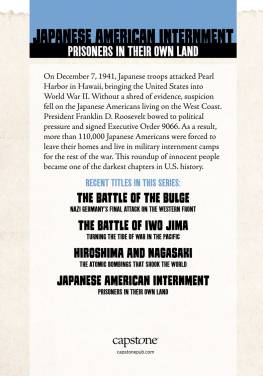

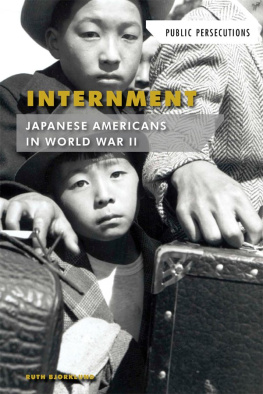

IN THE SPRING OF 1942, A FEW MONTHS AFTER THE JAPANESE attack on Pearl Harbor launched World War II in the Pacific, the United States Army, acting under authority granted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt and confirmed by Congress, summarily rounded up the entire ethnic Japanese population living on the nations Pacific Coast. These American citizens and longtime residentssome 112,000 men, women, and childrenwere packed into military holding centers for several weeks or months and then transported under armed guard to the interior of the country. There they were confined in a network of hastily built camps constructed and operated by a new federal agency, the War Relocation Authority (WRA). Although some of these inmates were able after a time to leave the camps and resettle outside the West Coast, most remained in captivity for the duration of the war.

This official action, commonly called the internment of Japanese Americans but more accurately termed their confinement, has often been referred to as the worst civil rights violation by the federal government during the twentieth century. While the governments actions did bring significant pain and hardship to those affected, there was no mass torture or starvation, and sympathetic officials and outside workers worked to ease the situation. In that sense, the suffering of the inmates in the WRA camps was not comparable with that of the masses caught in the agony of total war or targeted by tyrannical regimesthe prisoners in the Nazi death camps, for instance, or the Chinese people under the Japanese occupationor with the historic degradation of African Americans, although such comparisons are inherently troublesome. Rather, what is particularly noteworthy about the confinement of the Issei and Nisei is its fundamentally ironic character: The WRAs total budget through 1945 was $162 million. In addition, the army spent an estimated $75 million to round up and remove Japanese Americans. In vivid contrast, the Japanese community in Hawaii, whose members were not singled out for wholesale confinement, made exemplary contributions in the form of volunteer soldiers and war workers. Finally, army officers and Justice Department officials, who sought to assure the orderly release of inmates from the camps and their scattering into communities outside, resorted to manipulating evidence and covering up information about the initial removal policy to defend it from judicial review.

The wartime confinement of Japanese Americans remains not only a critical event in the Asian American experience, but a resonant point of reference and touchstone of commemoration for diverse groups of Americans. Dozens of works have appeared describing the signing of Executive Order 9066, the presidential decree that undergirded the action, as well as the court challenges to the governments actions. An equally large literature has sprung up on the camp experience of the inmatestheir family relations, their schooling, their resistance, and even their artistic creations. These works have rightly focused on Japanese Americans as important actors in shaping the nature of government policy and camp life, despite the numerous limitations on their freedom and the economic and psychological burdens they faced as a result of confinement. The inmates helped staff and operate schools, churches, hospitals, and cooperative stores. In conjunction with camp administrators, and sometimes in defiance of them, they organized social groups, sports competitions, musical bands, literary magazines, and crafts classes. They also struggled to preserve autonomy from invasive camp administrations. Using their limited channels of self-government, they called for redress of grievances, and on several occasions they expressed their resistance through organized strikes or even rioting. More negatively, hard-line factions of inmates organized harassment and sometimes violence against suspected informers, or those considered too friendly to camp administrators.

Next page