Contents

Guide

Copyright 2020 by John Tateishi

All rights reserved. No portion of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from Heyday.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Tateishi, John, 1939- author.

Title: Redress : the inside story of the successful campaign for Japanese American reparations / by John Tateishi.

Other titles: Inside story of the successful campaign for Japanese American reparations

Description: Berkeley, California : Heyday, [2020] | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019045837 (print) | LCCN 2019045838 (ebook) | ISBN 9781597144988 (cloth) | ISBN 9781597145053 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Japanese Americans--Evacuation and relocation, 1942-1945. |

Japanese Americans--Reparations. | Japanese Americans--Civil rights. |

Japanese American Citizens League. National Committee for Redress--History. | Tateishi, John, 1939

Classification: LCC D769.8.A6 T383 2020 (print) | LCC D769.8.A6 (ebook) | DDC 940.53/1773089956--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019045837

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019045838

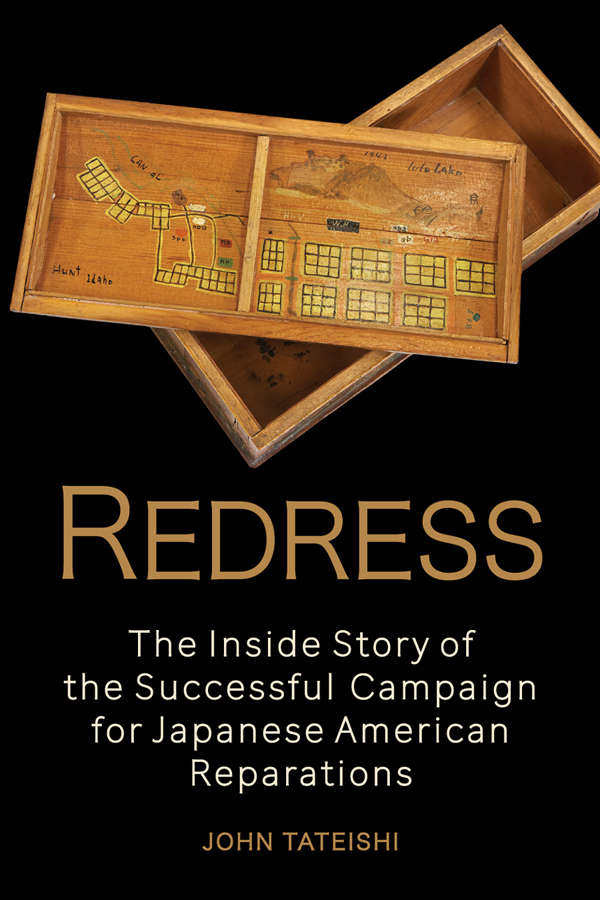

Cover Art: Handcrafted wood box with sketches of Tule Lake and Minidoka (Hunt, Idaho) Relocation Centers, 1943. Fusaichi Frank Hyosaka Artifact Collection, Japanese American Service Committee Legacy Center Archives and Library, Chicago. Used by permission.

Cover Design: Ashley Ingram

Interior Design/Typesetting: Ashley Ingram and Marlon Rigel

Published by Heyday

P.O. Box 9145, Berkeley, CA 94709

(510) 549-3564

heydaybooks.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

PREFACE

When my son, Stephen, was in kindergarten, his teacher was reading a story to the class in which some kind of miracle occurs. She stopped and asked the students if anyone could explain what a miracle was. Stephen raised his hand and answered, Its something that cant happen, but does.

Five years later, in 1980, I was doing an interview with Bernard Goldberg, who was at that time the West Coast reporter for the CBS Evening News. Earlier that week, he had watched a news item about the World War II incarceration of Japanese Americans on KPIX, the local San Francisco CBS affiliate, and he called me to talk about our seeking redress for the injustice of our treatment during the war. I was then the chairman of the National Committee for Redress for a national civil rights organization called the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL). My responsibility was to continue to develop the framework of the issue, but I had decided instead to launch a campaign that would seek an apology and monetary compensation from the United States government for the forced removal and imprisonment of the entire West Coast Japanese American population during World War II. What interested Goldberg was that the JACLs redress campaign went far beyond a demand for monetary reparations. In pushing for an official apology, it sought to prevent the United States from ever repeating the treatment we had experienced in wartime.

The story that aired on KPIX was the first time the topic of incarceration and redress had aired as a major news story anywhere in the country. Goldberg wanted to interview me about the JACLs redress campaign, which by then had begun to gain public attention. At that time, hardly anyone outside the Japanese American community knew anything about the internment, and I knew that we could not even consider a legislative battle until we educated the American public about the wartime experiences of Japanese Americans and convinced the majority that a grave injustice had occurred. I knew that our most effective tool toward achieving this goal was to use and exploit the media, so when Goldberg called to ask for an interview, I welcomed the opportunity.

As we sat chatting at the JACL national headquarters building in San Francisco while his crew set up their equipment, he asked me what odds I gave to the campaigns success.

Optimistically, maybe about a thousand to one, I said.

Goldberg looked at me and told me he had talked to colleagues and to political contacts in Washington to ask what they thought, and not a single person believed it was possible. They all agreed it would take a miracle for us to succeed.

So there it was, that word: miracle. Something that cant happen, but does.

As it turned out, there was no miracle that led to the success of the Japanese American redress campaign. No one person stepped onto the scene, and no single action turned the tide in our favor. Did we have luck? Yes, there was plenty of luck and good fortune, but mostly it was hard work and perseverance and an undaunted belief in American idealism that allowed us to conquer a Sisyphean task that no one thought was possible.

In the decades since, a few books and several articles have been written about the Japanese American redress campaign, each with different perspectives, each with different heroes. Ive not read them allonly a couple, to be honest, because I pretty much know the story they tell about the separate pieces of the campaign as their authors understand it. You put those separate pieces together and what you get are the different parts of a puzzle that forms a larger picture of an extraordinary campaign. Its much like Henry Jamess comment in his preface to The Portrait of a Lady, about seeing a figure in a house through different windows: the image varies in shape and form depending on the window through which one observes the figure. I learned as a student at UC Berkeley that historical narratives are like that, a reflection of the multitude of factors and influences that shape the narratives of any factual account.

Ive found this to be true about the WWII internment and the redress campaign, both of which I experienced firsthand: one as a child and the other as a person at the helm of an often acrimonious and always volatile national effort to set the historical record straight.

I first wrote the manuscript for this book in 2007, with the intent to record the history of the Japanese American redress campaign from my perspective, beginning with my earliest involvement until I left the campaign, and then my subsequent involvement in events following the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001. The parallels between the strikes on Pearl Harbor and the World Trade Center towers were obvious; the moral imperative for us to do whatever we could to prevent a repetition of our wartime experience was compelling.

For years I was prompted to write the history of the redress campaign at the urging of Senator Daniel Inouye (D-Hawaii), who kept telling me I was the only one who knew the real story and the immense obstacles we faced from the earliest stages of the endeavor through to the very last effort. My response to him always was that I couldnt write an accurate history of the campaign without airing the dirtythe sometimes disgustingly dirtylaundry that would need to get hung out on the line with the rest of the facts. Too many people had already been hurt, I told him, and I had no desire to expose those who had forgotten who we were as a community.