Contents

Guide

Copyright 2018 by Charles Wollenberg

All rights reserved. No portion of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from Heyday.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Wollenberg, Charles, author.

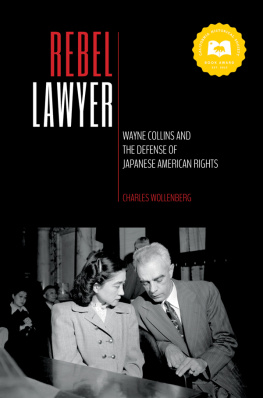

Title: Rebel lawyer : Wayne Collins and the defense of Japanese American rights / Charles Wollenberg.

Description: Berkeley, California : Heyday, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017058739 (print) | LCCN 2017058803 (ebook) | ISBN 9781597144391 (E-pub) | ISBN 9781597144360 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Collins, Wayne (Wayne Mortimer), 1899- | Lawyers--United States--Biography. | Japanese Americans--Civil rights. | World War, 1939-1945--Japanese Americans. | Japanese Americans--Legal status, laws, etc.

Classification: LCC KF373.C635 (ebook) | LCC KF373.C635 W65 2018 (print) | DDC 341.6/70973--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017058739

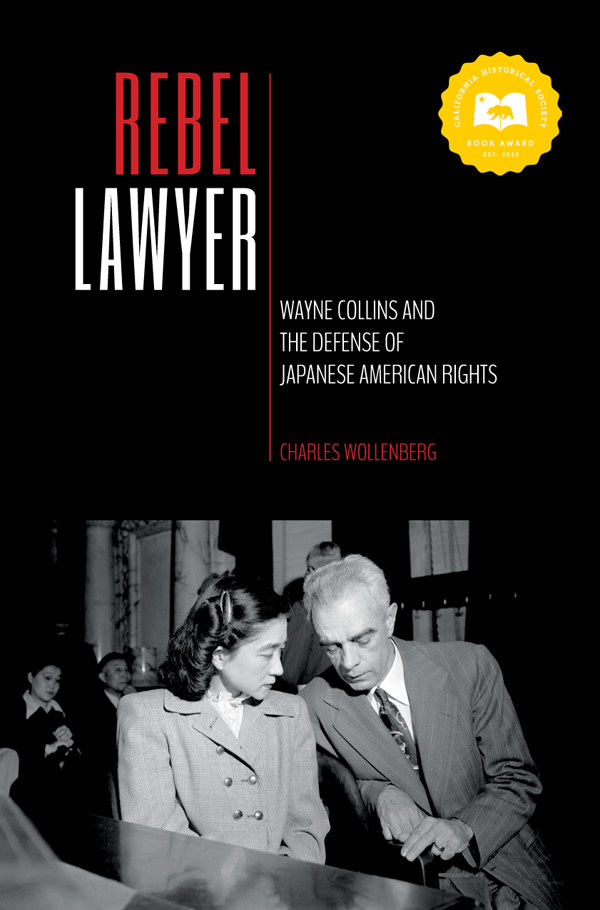

Cover Art: Wayne Collins with Iva Toguri, 1949. Barney Peterson, San Francisco Chronicle, Polaris.

Book Design: Ashley Ingram

Orders, inquiries, and correspondence should be addressed to:

Heyday

P.O. Box 9145, Berkeley, CA 94709

(510) 549-3564, Fax (510) 549-1889

www.heydaybooks.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

PREFACE

CHAPTER 1: 9066

CHAPTER 2: REBEL

CHAPTER 3: KOREMATSU

CHAPTER 4: TULE LAKE

CHAPTER 5: RENUNCIANTS

CHAPTER 6: CITIZENS

CHAPTER 7: TOKYO ROSE

CHAPTER 8: PASSING

CHAPTER 9: VICTORIES

CHAPTER 10: PRECEDENT

SOURCES

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE CALIFORNIA HISTORICAL SOCIETY BOOK AWARD

When I was a graduate student at UC Berkeley many years ago, my professors warned me against present-minded history, historical writing that imposed the standards and values of the present upon the past. The professors argued that you had to accept and understand the past on its own terms, rather than through the lens of present-day morality. (Even then, I wondered how you would practice that principle when writing a history of Nazi Germany.)

In this study of Wayne Collins and his defense of Japanese American rights, however, I found that present-minded history was not the problem. Instead, it seemed that Collinss standards and values and the issues he was confronting in the 1940s were dominating the political and social landscape of the second decade of the twenty-first century. I began my research while Donald Trumps presidential campaign was appealing to a wave of nativism and anti-immigrant feeling. While I was writing the manuscript, lawyers objecting to President Trumps executive order banning certain Muslim immigrants were using many of the same arguments that Collins had used to oppose President Franklin D. Roosevelts executive order authorizing the removal and imprisonment of Japanese Americans. Writing about Collins left me considering a history-minded present rather than a present-minded history. One friend recently asked me where was Wayne Collins when we really needed him?

This book is not a full biography of Wayne Collins. While it covers some aspects of his personal life, it gives little attention to his private law practice and other business ventures. Instead, the book concentrates on Collinss legal fights for Nikkei rights, and it attempts to put these legal battles into the context of the larger history of Roosevelts Executive Order 9066 and the policies it promoted. My argument is that the United States Constitution is not self-starting; it needs human intervention to transform its noble words and principles into concrete reality. It takes a particular combination of moral commitment, political conscience, and downright stubborn rebelliousness to intervene on the side of individual constitutional rights in times of national crisis, such as war. Collins had that combination of personality and character. He was hardly a flawless human being, but he was a fearless defender of the nations most important constitutional principles. Many of those principles are under attack today, making Collinss legal efforts in defense of civil rights and civil liberties all too relevant in the twenty-first century.

I had a lot of help learning about Wayne Collinss life and times. In particular, his son, Wayne Merrill Collins, generously answered questions about his fathers family and professional life. I had access to the vast collection of the Wayne M. Collins Papers at The Bancroft Library on the UC Berkeley campus, as well as sources at other branches of the university library. The archives of the Northern California branch of the American Civil Liberties Union at the California Historical Society was another valuable resource. I also used materials from the San Francisco Public Library and the Special Collections of the UC Davis Library. I am grateful for the immense good work and dedication of the librarians and archivists at all these institutions.

Kathy, Leah, and Mike Wollenberg, along with Stan Yogi, Patricia Wakida, Jerry Herman, Tom Wolf, and Martha Bridegam read the manuscript and gave important criticisms and suggestions. I had valuable conversations with Anthea Hartig, Alison Moore, and John Tateishi, as well as feedback from Elaine Elinson, and a session at the National Japanese American Historical Society.

Finally, I am grateful to Heyday, its publisher Steve Wasserman, and especially for the support and assistance of its editorial director, Gayle Wattawa. I greatly benefited from the careful work and good advice of my Heyday editor, Briony Everroad. The book received the 2017 California Historical Society Book Award. The award is a tribute to the importance of Wayne Collinss historic fight for justice and its relevance to California and the nation, both past and present.

Although Hiroshi Kashiwagi was only twenty-two years old at the time, he says that he was already at the low point of my life when he met Wayne Collins in the summer of 1945. A native of the Sacramento Valley, Kashiwagi had spent three years confined at the Tule Lake Segregation Center in northeastern California. Earlier in 1945, he had made a terrible mistake, joining five thousand other Tule Lake inmates in renouncing their American citizenship. He said he had been a victim of the governments manipulation, of the hysteria within the camp, of the confusion in our family, and of my own stupid inertia. Now the government classified him as a native American alien subject to deportation to Japan, a nation he had never even visited. All that stood between Hiroshi Kashiwagi and involuntary exile was Wayne Mortimer Collins, a small wiry looking man with short gray hair and bright sharp eyes. Kashiwagi could not believe that this very Caucasian man, a refined, intense civil rights attorney from San Francisco, smoking incessantly, was actually on our side, outraged at our miserable situation.

What brought Kashiwagi and Collins together was Executive Order 9066, issued by President Roosevelt in February 1942, about three months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The executive order authorized the army to remove all people of Japanese descent from the West Coast of the United States. One hundred and twenty thousand individuals were affected, men and women, adults and children, Issei (first-generation immigrants prohibited by law from becoming American citizens), Nisei (second-generation Japanese Americans who were US citizens by virtue of their American birth), and a very few Sansei (third-generation citizens of Japanese descent). The evacuation even applied to Japanese American infants in West Coast orphanages. The government first housed the Nikkei (all people of Japanese descent), in crude temporary assembly centers and then in ten somewhat more elaborate camps, including Kashiwagis Tule Lake Segregation Center.